Revolutionary Era and its Aftermath

Penn’s founder, Benjamin Franklin, always had a deep appreciation for France and the French language. Franklin was to be the first Minister to France and his efforts were instrumental in getting France to back the American War for Independence. In Philadelphia, students began learning French at the Academy (which would become the College a year later) in 1754. The first officially titled Professor of French was Paul Foucaud in 1766. Among the first men awarded honorary doctor of law degrees at Penn in 1782 were Frenchmen. One was awarded to Major General François Jean de Beauvoir Chastellux, who had served under General Rochambeau and participated in the Yorktown campaign. Another was presented to the Consul General of France to the United States, François Barbé-Marbois. Three other honorary degrees were awarded to Frenchmen who had been medical officers.

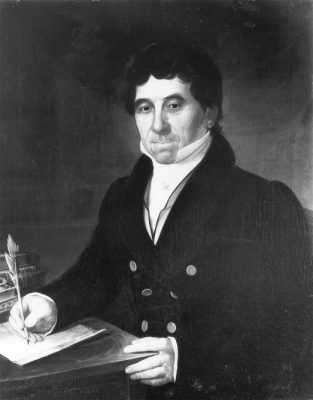

In 1784, King Louis XVI, as the revolution at home had not yet begun, sent a gift of one hundred books to the University Library. The Marquis de Lafayette, a French hero of the American War for Independence, received an honorary doctor of law degree from the University in 1787. Jean Baptiste Clement Rousseau (pictured at right), the first French student of the University’s Medical School, graduated with the Medical Class of 1800. Emperor Napoleon I sent the French-Chinese Dictionary as a gift to Penn’s Library in the early nineteenth-century. Lafayette, surviving the previous crises in France in 1824 arrived in Philadelphia with his grandson, George Washington Lafayette, and both of them became honorary members of the Philomathean Society. General Lafayette, having renounced the title of Marquis during the French Revolution, was awarded a second honorary doctor of laws degree by the University, which had somehow managed to forget that they had already presented him with one almost thirty years prior.The Nineteenth Century

The first class to graduate from the new Dental School in 1879 had two Frenchmen. Le Cercle Francais at the turn of the century invited to the campus two well-known French writers to give lectures – Henri de Régnier the poet and Edouard Rod the novelist. In 1904, an honorary doctor of laws degree was presented to Jules Jusserand, the French Ambassador, who would return again to the University of Pennsylvania in 1914 to give the commencement address. The former French Empress Eugenié (wife of Napoleon III), sent a letter to the Penn campus in 1913 “congratulat[ing] you [Penn] upon the realization of the generous thought of Dr. Thomas Evans,” who had been the court dentist of her late husband. Evans himself had once saved the Empress’ life. Upon Napoleon III’s capture, Eugénie safely fled Paris in Evans’ carriage (pictured at left), as the city flared into riots, and she made it to England. In 1914, the carriage was sent from Paris to the Thomas Evans’ Museum at the Dental School as stipulated by his will.

World Wars I and II

It seems that it is these relations with France at the turn of the twentieth century and Penn’s involvement in World War I, though, which would cement the relationship between the University of Pennsylvania and France even more so than in the past. A section of this report has already examined Penn’s involvement in the first World War, but to briefly reiterate Penn’s involvement in France at the time, what needs to be mentioned is Penn’s work in the American Ambulance Service in Paris, and Base Hospital No. 20 located in Puy-de-Dôme, near the center of France. For a period of eight months with approximately 9,000 cases, the Base Hospital was active there and the staff was made of mostly Penn men. This does not mention those who fought actively in France during the war. Paul P. Cret, a Frenchman and famous architect who had been a Professor of Design at Penn returned to France for a period of time during the war to serve his homeland. Prior to this, Cret had received an honorary degree at Penn in 1913.

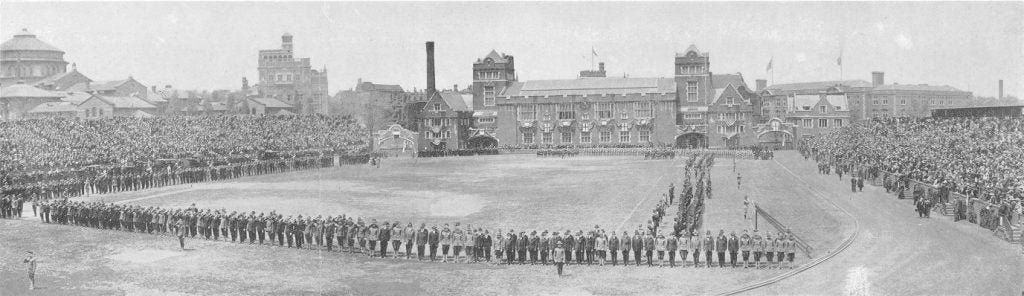

In May 1917, René Viviani, Prime Minister of France during the first year of the war and later Minister of Justice and General Caesar Joseph Joffre, the Commander-in-Chief of the French army from 1914 to 1916, the first Marshal of the French Third Republic, head of the French Military Mission to the United States and in 1918 the head of the Supreme War Council. Known as the “Victor of the Marne,” he and Viviani were awarded honorary doctor of law degrees from Penn (pictured at right). Their arrival on the Penn campus and appearance on Franklin Field was truly spectacular, as recounted in Old Penn:

In 1921, another two honorary degrees were awarded. The first went to Marshal Ferdinand Foch, a French general in World War I and made a Marshal of France in 1918, he was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies and accepted the German surrender on November 11, 1918. The second honorary degree was awarded to Madame Marie Curie, a French physicist and chemist, the first female professor at the Sorbonne and the winner of two Nobel prizes (in 1903 and 1911). She was recognized for her work in the field of radioactivity.It was an impressive sight. Every student recruit within the field stood at attention, every person in the stands stood, every man with head uncovered. As the first automobile came through the arched gateway the University band stationed in front of the gymnasium struck up the French National anthem, “The Marseillaise.” Behind the band a chorus of nearly 1000 students from the Masque of American Drama led in this noble anthem, and the strains were taken up throughout the stands as the motor cavalcade passed around the track. The visitors were deeply moved. Commissioner Viviani kept his hat removed and bowed repeatedly, while Marshal Joffre, Vice Admiral Chocheprat and the other military and naval members of the party kept their hands up in a continuous salute. As the automobiles bearing Viviani and Joffre passed section after section, there was a continuous roar of cheers, while above all could be heard the martial strains of “The Marseillaise.”(pictured below)

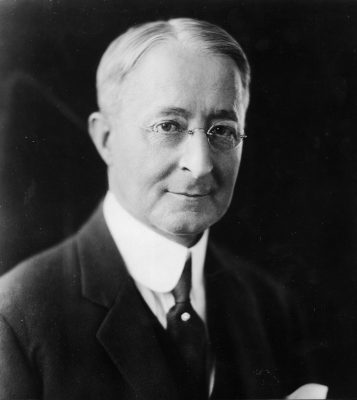

In October 1933, a group of notable French citizens came to the Penn campus. Among this group (pictured at right) were included Mme. Maunoury, the widow of the former Minister of the Interior under French President Poincaré, Paul Balbaud, then the Counselor of Foreign Commerce, Francois Latour, the General Budget Officer of the City of Paris and Monsieur and Mme. Liorel, as well as engineers, industrialists and economic students. The group was especially interested during their tour of the Penn campus in the Moore School of Electrical Engineering and the Towne Scientific School. A year later in 1934, Dr. Josiah H. Penniman (pictured at left), then the Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and an English Literature Professor, was awarded, by the President of the French Republic, the Cross of the Legion of Honor of France. The French Consul General in Philadelphia, Marcel deVerneuil, presented the award to him in College Hall. The next year, on May 8, 1935, under the auspices of the Philadelphia Chapter of the American Association of Teachers of French, a meeting was held in Houston Hall to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Victor Hugo’s death. In February 1940, the French Ambassador to the United States at the time, his Excellency M. Rene Doynel de Saint-Quentin, came to the Penn campus for the activities during Founder’s Day Exercises. It was the Bicentennial Year for the University of Pennsylvania. Saint-Quentin placed a wreath on the Franklin Statue which stands in front of College Hall.

Penn’s involvement in World War II is also covered in another section of this report. Nothing need be re-examined here, though without a doubt, Penn men fought as part of American forces in France during the war. On the campus, on April 18, 1945, Captain Louise Mont-Ruinaud, who had been an underground leader of Maquis pilots (they would rescue those Allied pilots who had been shot down by the Germans and get them out of occupied France to England for aid), spoke about her experience in the war in Houston Hall. About three hundred attended the presentation. In 1947, Simone de Beauvoir, a French philosopher and an author, came to the Penn campus and gave a public lecture (delivered in French) at the University Museum.

Later 20th Century

In the 1970s, many events at Penn shaped its relations with France. The Ars Antiqua de Paris (pictured at right) came to the Penn campus in 1970 under the auspices of the French Government (the French Fifth Republic). The ensemble was composed of four musicians who presented Medieval and Renaissance music at the campus, and had been on a tour of the United States. That same year Pierre-Paul Schweitzer, then the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) addressed graduate students of the Wharton School. Schweitzer was a notable man, having worked in the French Treasury as early as 1936. An active member of the French Resistance, he spent a period of time in a German concentration camp. He also worked in the French Embassy in Washington, D.C. and in 1960, began work at the Bank of France as Deputy Governor. A commander of the Legion of Honor and a holder of the Medaille de la Resistance and the Croix de Guerre, his presence at Penn was not taken lightly. In 1976, the same year as the Bicentennial Celebrations of the United States, Penn awarded an honorary degree to Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, then the President of the French Fifth Republic. The degree was awarded to d’Estaing by Penn President Martin Meyerson.

As of 1975, Penn had been working at the Chateau de la Napoule in Cannes, France, and was thinking about accepting the chateau as well as some other properties in that location as a gift to the University, though in 1981, the Clews family (Henry Clews had originally owned and built the Chateau) wished for its return and the University agreed to withdraw from the property. Humphrey R. Tonkin, then the Director of the Office of International Programs at Penn stated in an article appearing that year in the Daily Pennsylvanian that “[he thought] generally having the chateau caused [Penn] to think hard about [its] activities in Europe…” though it is clear from Tonkin’s other statements that Penn turned its interests to other possibilities for that closer link to Europe.