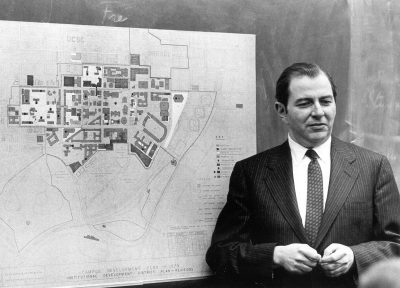

The Trustees selected Martin Meyerson to succeed Gaylord Harnwell when they unanimously elected him president at their meeting on 28 January 1970. Meyerson had enormous shoes to fill when he took office on the first of September. The Educational Survey and the Integrated Development Plan of the Harnwell era set the pace for ambitious and aggressive strategic planning and fundraising for the new administration. Luckily, Meyerson could boast enormous experience in the field of urban planning. In fact, he had even served as Professor of City and Regional Planning at the University’s Graduate School of Fine Arts from 1956 to 1957. He also boasted years of administrative experience. Meyerson successfully picked up where Harnwell left off by designing and implementing an extensive educational plan at the beginning of his tenure and a wildly successful fundraising initiative towards the end of his tenure. Minorities and women also made important strides towards achieving equality at Penn during the Meyerson administration, as he designed and continuously revised a detailed affirmative action plan throughout his term.

At the onset of his presidency Meyerson outlined a number of educational goals he hoped to accomplish. In January 1972 he released Directions for the University of Pennsylvania in the Mid Seventies to the Trustees. In this progress report Meyerson revealed plans to attract new sources of funding in order to increase the University’s endowment. He made other suggestions for: extending and reinforcing professional training; correlating educational programs; strengthening undergraduate professional programs; allowing undergraduates to pursue graduate options; expanding undergraduate opportunities; focusing on good programs; and creating new interdisciplinary programs. The most important revelation Meyerson made in this document was his plan to create a University Development Commission, comprised of faculty and students who would evaluate and make suggestions for educational improvement.

Meyerson also unveiled plans to make undergraduate education a priority early on in his tenure. In October 1971 Meyerson and Provost Curtis R. Reitz called an open Conference on Undergraduate Education, which enlisted the efforts of faculty, staff, and students. The conference consisted of twelve different workshops made up of 10-15 members of the Penn community. Each workshop reviewed a different aspect of undergraduate education:

- Combined Degree Programs and Calendar Changes

- Pre-medical Education

- Vocational Decision Making and Advising

- Goals of Undergraduate Education at Pennsylvania

- Student-Faculty Academic Interaction

- Teaching Methods

- Accreditation and Certification

- Undergraduate Professional Education

- Extending Education Outside the 18-21 Age Group

- Teaching Incentives and Evaluation

- Intellectual Lifestyle Outside the Classroom

- Special Programs

While none of the changes proposed by the various workshops in Reinforcement and Change in Undergraduate Education were considered final, their work strongly influenced the development of undergraduate education at Penn during the 1970s.

The most famed educational planning initiative of the Meyerson era began its work in February 1972. At their meeting on 11 February the Trustees determined that representatives from the faculty, from the student body, and certain administrative officers would meet, discuss, and formulate recommendations for general policies regarding the educational objectives of the University. In May 1972 the work teams released their first progress reports to the Trustees. University Development Commission: Summary of Progress Reports of the Work Teams described the Commission’s work in the areas of: reallocation; undergraduate education; educational living patterns; endowed scholarships and fellowships; endowed professorships; libraries; intra-university cooperative programs; inter-institutional cooperative programs; continuing education; audiovisual resources; graduate education, and professional schools. The Commission highlighted the basic values of education at Penn, which included a dedication to teaching and scholarship, a new emphasis on excellence in teaching, sustained attention to undergraduate education, and matching the strength of the key professional schools in all other schools.

In February 1973 the culmination of the year-long Development Commissions study appeared in the form of the Commission’s final report, Pennsylvania: One University. The Development Commission ultimately made 94 recommendations for improving educational programs centered around five themes: educational directions, academic planning, tools for scholarship and learning, the changing membership of the University, and the arts and environment at the University. Meyerson published a follow-up document to the Development Commission, titled, The Implementation of the Development Commission Recommendations in February 1973. This report described action being taken towards making Penn “One University,” a phrase coined and popularized by Meyerson. The areas considered in the report included: reallocation of funds, undergraduate education, graduate and professional education, black presence, intrauniversity cooperation, continuing education, interinstitutional cooperation, endowed professorships, the library, and future planning. The University administration planned to act on the Commission’s recommendations as soon as possible. Two years later, in January 1975, the administration released another report describing the progress of the Development Commission, Second Report on the Implementation of the Development Commission Recommendations. By this time the University had successfully merged the College, the College for Women, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the social science programs previously housed in the Wharton School to create the new Faculty of Arts and Sciences. This second report described further improvements as related to the five key areas determined by the Commission’s final report from February 1973.

Not only did Meyerson work to improve education at Penn, but he also pushed to diversify the campus. Building on the national policy established by US President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, Meyerson introduced a comprehensive affirmative action plan for Penn in June 1971. At the 11 June 1971 meeting of the Trustees Meyerson requested that each school and department submit its own proposal for increasing the number of women and minority faculty, revising the nepotism rule, establishing a daycare center, and appointing an ombudsman. In February 1976 Meyerson issued a summary of Penn’s affirmative action plan as it had developed since 1971. The Affirmative Action Program of the University of Pennsylvania intended to hire more women and minority faculty and staff, but it also worked in earnest to maintain a standard of fairness. The 1976 publication reported on general principles for affirmative action in addition to principles for an academic setting and the specific affirmative action program for the University. The University’s affirmative action plan described responsibility; policies and procedures for non-academic personnel; policies and procedures for academic personnel; utilization analyses, goals, and timetables; and also included an internal audit and hiring analyses.

From the inception of the Affirmative Action plan it became clear that it specifically targeted the visibility of women and African Americans. In April 1971 a Committee on the Status of Women reported on “Women Faculty in the University of Pennsylvania,” which appeared in three installments in the Almanac. The Committee was charged with: collecting information on female representation in the various department and schools; soliciting views from members of the Penn community on female presence; studying the percentage of women in academic positions, including their rank and discipline; and making recommendations to ensure an equal representation of women. The Committee generally found that women were not fairly represented in the higher ranks. They also found that the University had a tendency to prefer male candidates over their female counterparts. In Part III they urged the University to increase the number of women faculty.

The African American presence at Penn also concerned the Meyerson administration. Although the Development Commission made recommendations for increasing the black presence at the University, the administration did not feel it did enough. As a result, Provost Stellar established a Task Force on Black Presence in August 1976. The Task Force submitted “Report of the Task Force on Black Presence” to the Trustees on 10 June 1977. In the report the Task Force proposed methods for supporting the black presence through the affirmative action program, undergraduate and graduate admissions, the curriculum, and through improving university life for African American students, faculty, and staff. After reviewing the report, even Trustee Kaysen admitted that the University had not done enough to solidify a strong African American presence on the campus. The Report of the Task Force on Black Presence, however, did reveal the Meyerson administration’s desire to both increase the number of African Americans on campus and improve the quality of life for Penn’s existing African American community.

While Martin Meyerson worked to improve the social and learning environments at Penn he also developed plans for a major fundraising campaign; he understood that he would never see his visions for the University realized if he didn’t have a sufficient amount of money at his disposal. The Trustees first resolved to launch a campaign to begin in 1975 at their meeting on 11 January 1974. The administration worked in secret over the next year. In October 1975, having already built a nucleus fund of $45.8 million, the Trustees announced a five year goal to raise $255 million. “Program for the Eighties” was motivated by Meyerson’s “One University” vision and therefore called for support from every single member of the Penn community. As the 7 October issue of the Almanac informed, “Trustee John Eckman outlined a comprehensive campaign plan in which no stone is to be unturned locally, nor across the nation.” The administration’s assertive effort made the campaign an enormous success. By the end of June 1980 the Program for the Eighties reached its goal. The campaign also ranked among the top three fundraising efforts by American universities in history.

While the administration focused its attention and energies on the Program for the Eighties, it also was forced to manage an extended period of hardship in University finances. Then, in March 1978, more than 1,200 students participated in a three-day student sit-in in College Hall in order to protest proposed budget cuts that would drop hockey and other sports, as well as the professional theater program at the Annenberg Center. The protest ended only when the Trustees, administrators, faculty, and students reached a settlement that promised to give students a stronger voice in University governance. A 31-point settlement agreement went as far as to give seats on the Board of Trustees to one student and one faculty member, a first for major private institutions. The administration also created a new “1978 Task Force on University Governance” in response to the sit-in. In its final report, the second Task Force on University Governance reviewed the 1970 Task Force’s Report (see Harnwell), analyzed the problems created by shrinking resources, and proposed changes, accordingly. The Task Force reaffirmed the experimental plan to offer seats on the Board to one student and one faculty member.

Martin Meyerson’s success is so impressive because he had to overcome extreme odds during his time as President. Not only did he face the immense task of following President Harnwell, but he also faced a failing economy that made maneuverability within the American university quite difficult. Meyerson did not let adversity affect him, however. When Paul Miller, Chairman of the Trustees, toasted Meyerson and his wife, Margy, at their farewell dinner on 29 January 1981 he praised:

Together they lifted the intellectual and societal aspirations of this community of scholars and increased the vitality of the University as an educational institution of international stature.

Meyerson molded “One University” characterized by excellence.