The Trustees instituted the Office of the President when they elected Thomas Sovereign Gates to the post on 6 October 1930:

The Trustees shall discharge all their executive duties through an officer who shall be styled “President of the University.” He shall be appointed by resolution of the Trustees at any meeting of the Trustees to hold office at the pleasure of the Trustees… Resolved: That Thomas S Gates be, and hereby is, elected President of the University.

Gates was an extremely well-respected Penn alumnus and Philadelphian who had already served as a Trustee of the University for almost ten years. He also worked closely with Josiah Penniman as the Chairman of the University of Pennsylvania Fund. The University certainly needed Gates’ knowledge and dedication throughout the 1930s and the first half of the 1940s, as the nation experienced some of the toughest times in its history.

The 1929 stock market crash and subsequent economic depression of the 1930s significantly affected the University’s enrollment and endowment; and even before 7 December 1941 World War II changed the face of academia in the United States by turning her schools into training camps for all the branches of the armed forces. The Gates administration dealt with adversity remarkably well as it was never willing to accept defeat. Gates developed educational programs and expanded the physical plant of the University throughout the duration of his term.

Because a highly organized and well-defined administration didn’t precede Gates, he encountered a number of loose ends and unfinished projects at the beginning of his tenure. One such project was an educational study of the curricula of the various schools. In June 1930, just a few months before Gates took office, Penniman requested a study to consider:

- Strengthening certain curricula

- Increasing the teaching load

- Designing a method to control research work

He also designated January 1931 as the due date for the committee’s report. At the meeting of the Trustees on 5 January 1931 the Committee reported that they had released new guidelines for teaching loads to the Board of Liberal Arts. At that same meeting Penniman, now Provost of the University, also reported on two important curricular issues: part-time courses and women’s education. Penniman further suggested that the University provide a separate women’s college, which in turn became a primary focus early in the Gates administration. By February 1933 the Committee on a College of Liberal Arts for Women submitted a College-approved report to the Trustees. Specifically the report recommended:

- That steps be taken to establish a College for Women by July 1, 1933 that provided a four year curriculum

- That the curriculum for the College for Women be the same as the College curriculum

Penn’s alumni magazine, The Pennsylvania Gazette, described the new Women’s College in its 15 April 1933 issue. “A Woman’s College” discussed the history of women’s education at Penn, revealing that plans for creating a separate school for female students first surfaced in 1882. The article also explained that the establishment of a Woman’s College was imminent in 1933 due to increasing female enrollment and the reorganization of the University’s School of Education. While the new Woman’s College segregated women students, it also awarded them more individualized attention, academically.

Women also enjoyed a significant development in educational opportunity at the very end of the Gates administration. The Committee on Policy and Planning established the School of Nursing in June 1944. The new school expanded the existing University Hospital-affiliated program by adding two years of preliminary college work; at the end of four years each student would be awarded a Bachelor of Science in Nursing. In “Establishment of a School of Nursing,” the Committee on Policy and Planning clarified the plans for the new program. In this report the Committee described: course of instruction, admission of students, fees, the necessary quota of women undergraduates, increased residential facilities, the degree, the inauguration of the plan, and continuation of the present hospital program. Like the Women’s College, the new School of Nursing gave women the chance to explore a variety of subjects while they received vocational training.

The education of women was not the only academic field in which the Gates administration made significant progress. The field of social science secured a couple of important victories as well. In February 1935 the University aligned itself with the Pennsylvania School of Social Work, creating a graduate professional program in the field. The Gazette reported on the establishment of the school in the 15 February 1935 issue in “Trustees Correlate Social Service.” According to the article, the new school reflected the University’s commitment to civil service. The Gazette explained that, in conjunction with the School of Social Work, the University also planned to establish a Bureau of Public Affairs. As Gates himself reflected,

A great university which has the duty of preserving and passing on knowledge of the past, -must also especially in a period of rapid social change such as the present, -keep abreast of the currents of the times and contribute its full share to the important tasks before us.

The School of Social Work provided both public and educational services. The Gates administration continued its social service efforts when it moved to create an Institute of State and Local Government in 1937. Gates announced a conference of teachers and investigators in the field of political science for the formation of the Fels Institute of the Wharton School in March 1937.

While Gates believed that strategic planning was extremely important for academic development, he also firmly believed that the character of the physical plant influenced educational practice. His plan to create a new campus at Valley Forge best reflected his feelings about physical development. In April 1929, a year before Gates officially became president of the University, Alumni President and Trustee Henry N. Woolman (College, 1896) decided to donate his Cressbrook Farm property at Valley Forge to the University. Ten years later Woolman conceded more property at Valley Forge to the University when he transferred the deed to his newly acquired Wilson Farm. By that time the administration had already designed an extensive plan for transferring a small number of educational programs to a campus at Valley Forge. The 22 May 1936 Minutes of the Trustees included “Digest of Valley Forge Plan,” which resulted from seven years of planning. The report named two primary goals for using the property:

- To develop an educational and residential unit at Valley Forge on a modest scale with a limited group of students to conduct an experiment in teaching and living. Further development would depend on success of the experiment

- To use the development of the supplementary campus for the benefit of the entire University both educationally and socially.

The Trustees emphasized the experimental nature of the Valley Forge education, but also expressed excitement for the curriculum they planned at the site, as it focused on “enlightened American citizenship.” The Trustees also believed that the smaller, more secluded environment would facilitate discussion and interaction among students and faculty members. This kind of interaction and study did not come cheap, however; a $585,000 price tag was put on the Valley Forge experiment.

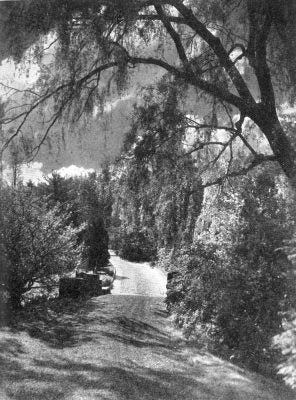

In spite of the expense the University’s Alumni strongly advocated for the Valley Forge plan. Throughout the 1930s the Gazette advertised the plan and called for support from all its readers. “Toward Valley Forge” appeared in the 1 July 1937 issue of the magazine. In addition to printing large photographs of the exquisite property, the article explained that moving a small number of Penn’s programs to Valley Forge would alleviate modern educational problems such as the impending “mass production” of education at universities resulting from increased enrollment. The article reiterated the Valley Forge Plan’s two major objectives and the cost of the program. “Toward Valley Forge” also articulated a number of benefits of the program including: cultural significance, close touch with the Philadelphia campus, individualized instruction, and new social and academic opportunities.

The Gates administration ultimately had to put the Valley Forge Plan on hold due to the War; however it received renewed consideration during the McClelland and Stassen administrations. While the University ultimately decided to expand the Philadelphia campus rather than construct a new campus at Valley Forge, the plan enjoyed a great deal of popular support throughout the Gates era.

Although Gates was unsuccessful in his attempt to create a new campus in the country, he was successful in acquiring a beautiful public garden and educational institution in nearby Chestnut Hill. The Trustees first proposed the creation of an Arboretum in April 1931. The administration made progress towards that end when Gates announced plans for the Morris Foundation and Morris Arboretum for use by the Department of Botany and other University Departments in October 1932. The Morris Arboretum was formally dedicated on 2 June 1933, as reported by the Gazette in “Morris Arboretum,” 1 June 1933. The Morris Arboretum represented a kind of Utopian sanctuary, removed from the bustle of the city and from the woes of everyday life in the early 1930s. The Gazette described,

With its wealth of trees, open stretches of lawn and meadow, plantings of non-shrubby character, winding brooks, grotto-greenhouses and excellent examples of ceramic art and statuary, the arboretum offers a variety of attractions, both to the layman and the scientist.

The historic public garden is still in operation to this day.

Another planning initiative that defined the Gates era was his major fundraising campaign, the Bicentennial Fund. After serving as Chair of the fledgling University Pennsylvania Fund of the Penniman administration, Gates realized the need to work incredibly hard to secure new sources of funding for the University. Using the University’s upcoming 1940 bicentennial as an impetus, Gates launched his new campaign in the spring of 1936. The 22 May 1936 Minutes of the Trustees included, “Bicentennial Financial Program of the University of Pennsylvania: General Needs.” These “general needs” included:

- Endowment for improving teaching in the undergraduate and graduate schools

- Endowment for improvement of teaching in the professional schools

- General University endowment

- Special Projects: Valley Forge campus, improvement of undergraduate and graduate scholarships, improvement of physical facilities, improvement of the University Museum

The Gates administration decided on a $12.5 million goal for the campaign.

The Gazette publicized the fundraising drive on 1 July 1936 in “The Bicentennial Campaign.” This article restated the general needs of the University, particularly focusing on the importance of improving teaching at the University and on the Valley Forge Plan. The Gazette‘s efforts to publicize the campaign proved rather significant because the magazine reached many of the University’s alumni. The way in which the administration connected the Fund to the 200th anniversary celebration of the University was another important publicity agent. Still, the Bicentennial Fund failed to reach even half of its proposed goal; by its close following the conclusion of the Bicentennial Celebration in September 1940 the Fund had only managed to raise $5 million.

While Gates’ fundraising efforts fell short, he proved his incredible expertise and administrative ability by guiding the University through one of the most serious events in the history of the nation and world. While the United States did not officially declare war on the Axis Powers until December 1941, many, including Gates, understood the inevitability of the nation’s involvement in World War II. In fact, he appointed a University Committee on National Defense as early as October 1940. Shortly afterwards, in December 1940, the Engineering School initiated a defense training program. After the United States declared war in December 1941 the University stepped up its efforts, particularly after Provost McClelland attended the meeting of the Association of American Colleges on 3-4 January 1942.

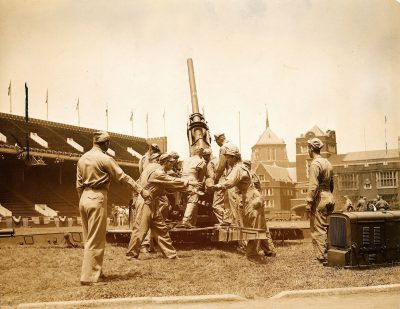

In the Minutes of the Trustees for 9 January 1942 a Committee on Acceleration recommended that a number of summer programs for accelerating the completion of degrees in Engineering, Law, and Medicine be implemented. At this same meeting Vice President Musser informed the Trustees that the Army had suggested that students in the service be given correspondence courses and that they also receive rehabilitation services after the war. By the beginning of 1943 the University was training young men in the United States Naval Flight Preparatory School and Navy College Training Program, in addition to offering its own Medical Officer’s Training Program. The University also housed an Army Specialized Training Program. The University worked diligently throughout the duration of the war. The Gazette reported on the University’s contributions to the war effort monthly. In January 1944 the National Council on Education reported that the University of Pennsylvania, with over 2,700 service men in training, ranked fourth in the number of trainees receiving instruction, nationally; when the men involved in the Naval Preflight School were included Penn ranked first.

Thomas Sovereign Gates’ devotion to the University of Pennsylvania allowed him to persevere through the toughest of times. Considering his limitations, Gates was remarkably proactive as President of the University. His close relationship to the Board of Trustees allowed him to create effective and innovative plans that allowed the University to make significant strides during the 1930s and early 1940s.