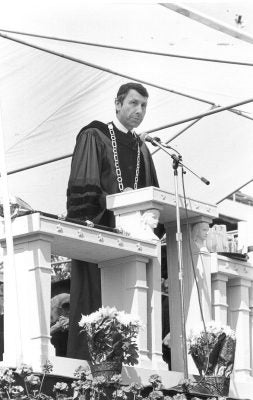

On 24 October 1980, the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania elected Francis Sheldon Hackney to succeed Martin Meyerson, effective 1 February 1981. Hackney came to Penn after having served five years as President of Tulane University and three years as Provost of Princeton University. When Hackney arrived at Penn he also joined the faculty in the Department of History. The successful conclusion of Meyerson’s fundraising campaign, “Program for the 80s,” allowed Hackney to develop ambitious plans for educational reform, which called for the diversification of the faculty and student body, expanded financial aid options, and an overhaul of the undergraduate program. Hackney was dealt an early blow, however, when United States President Ronald Reagan made major cuts in federal funding for higher education. Reagan’s economic policy forced the Hackney administration to seek new sources of funding in order to allow Penn to maintain the need-blind admissions policy that the University had instituted in the mid 1960s.

In January 1982, less than a year into his administration, Hackney published a prototypical planning document, known as Six Working Papers for Strategic Planning. Hackney initiated this planning process along with the provost, deans and other officers of the University. The key areas considered by the six groups that authored the Six Working Papers included: minority faculty and students, undergraduate education, research capacity, educational outreach, and ties with the city of Philadelphia. The Six Working Papers made important suggestions for adding new administrative posts that worked towards increasing the minority presence, increasing the number of standing faculty that regularly taught undergraduates, consolidating graduate programs, implementing more centrally controlled research efforts, and defining Penn’s commitment to the city of Philadelphia as one of its primary educational goals. As part of the planning process, President Hackney and Provost Thomas Ehrlich invited commentary from all members of the University community, including the administration, faculty, students, and staff. The Six Working Papers coupled with that commentary provided the framework for the planning initiative Hackney became most well-known for: Choosing Penn’s Future.

In January 1983, Hackney made public his comprehensive plan for the University: Choosing Penn’s Future. When the Trustees considered the document at their meeting on 21 January 1983, Hackney explained the significance of its title:

Even though the times are stringent and we are facing challenges, we can still be masters of our fate if we take action deliberately and thoughtfully and very forcefully.

President Hackney was strongly committed to providing the University with the ability to choose its own fate. In the brief, yet aggressive plan Hackney identified three special challenges: undergraduate education, the research experience, and student aid and financial assistance. For each of these “special challenges” Hackney named a specific goal. He hoped to make undergraduate education the responsibility of the entire faculty, and thus, “shrink the psychological size of the University.” He also hoped to assess and improve the research facilities in order to attract promising students at the graduate level. In order to increase financial aid options for students he wanted to develop new ways for stretching existing funds. Hackney’s plan for Choosing Penn’s Future ultimately established a framework of four priorities: the University’s quality was contingent upon the strength of the faculty, the University had to conserve resources, the University had to maintain a community of diverse peoples and interests, and the University had to conserve its academic integrity through the quality of the student body and research efforts. Hackney considered these four priorities to be the main staples of his educational planning at Penn for the next ten years.

In Choosing Penn’s Future Hackney made strengthening undergraduate education at Penn one of his primary areas of focus. In fact, it was in Choosing Penn’s Future that he mandated a Faculty Council on Undergraduate Education. The Council – chaired by Provost Ehrlich and comprised of twenty faculty members and three students representing all twelve schools, the Vice Provost for University Life and the chairs of the school curriculum committees – was charged with “recommending a set of curricular options and instructional mechanisms for university undergraduates that draw on strengths, experiences, and academic perspective from faculty from the liberal arts and professions.” The Council worked over the next four years. In their numerous “Reports on the Work of the Faculty Council on Undergraduate Education” the Council designed and implemented plans for: a University-wide, interdisciplinary course in applied ethics; a “New Student Week Lecture Series”; a series of new courses for first and second year students known as, “The Human Experience;” numerous undergraduate research options; new dual degree programs in cognitive science, international area studies, aging, the new economy, and public and urban policy; and other curricular reforms and improvements. The Council’s efforts proved extremely critical to elevating the status of the undergraduate program to that of Penn’s highly-respected professional programs.

In January 1985 Hackney released Investing in Penn’s Future, a planning document built on the framework of Choosing Penn’s Future. Investing in Penn’s Future outlined a five-year commitment for strengthening Penn, in which undergraduate education, research excellence, and student financial assistance remained the focus. In the document Hackney acknowledged Penn’s need to respond better to changes occurring in the world of higher education: technological advancement and demographic changes, including a reduction in the number of college-age students seeking degrees and the looming retirement of postwar scholars. These changes had important implications for the University. In order to keep up with these changes and prevail as a top institution Penn needed to revise undergraduate study to include more diverse educational programs such as interdisciplinary majors, joint degrees, and interaction between liberal arts and professional education. Revamping the freshmen year also became a primary focus. In order to maintain excellence in research, Hackney advised that Penn invest $250 million in new and renovated buildings and equipment. When discussing student financial aid and assistance Hackney emphasized the popularity of the Penn Plan. The Penn Plan, first introduced on 9 September 1983, assisted families in funding undergraduate education. It also strengthened Penn’s need-blind admissions policy. Investing in Penn’s Future reinforced Hackney’s strong desire to further Penn’s status as “One University.”

In the spring of 1987 Hackney unveiled Investing in Academic Excellence, another planning document that elaborated on Choosing Penn’s Future. Investing in Academic Excellence detailed plans to ensure Penn’s prominence in the 1990s. Improving and sustaining the faculty was a primary concern. As a result, the plan called for:

- A major breakthrough campaign to supply resources

- Increased research and instructional support for the faculty

- Augmentation of current faculty through the recruiting of major scholars in the prime of their careers.

The plan also reaffirmed undergraduate education, research excellence, and student financial aid assistance as the University’s priorities and announced Penn’s next steps for beginning the campaign.

The “major breakthrough campaign” proposed in Investing in Academic Excellence certainly lived up to its description when, in October 1989, Hackney and the Trustees chose “The Campaign for Penn: Keeping Franklin’s Promise” as the administration’s major fundraising drive. As The Almanac revealed in “‘Keeping Franklin’s Promise’ is the Billion Dollar Goal,” the Campaign for Penn set a one billion dollar goal to be achieved over the course of five years. According to the Trustees, in 1986 the University had begun to lay the foundation for the Campaign by conducting a comprehensive assessment of Penn’s strategic objectives and funding needs by evaluating the University’s fundraising capacity and by soliciting gifts from the Trustees and from friends in order to build momentum. The billion-dollar goal broke both University and Ivy League records. Further, the Campaign earmarked ½ of the funds for arts and sciences education while providing for 150 new endowed professorships. By the meeting of the Trustees on 20 October 1994 the Campaign for Penn had exceeded its original $1 billion goal. It raised $1.33 billion and tripled the University’s endowment.

Because the Campaign for Penn was so successful, Hackney moved forward with even bolder planning proposals for the early 1990s. In December 1989 the administration released Planning for the 21st Century: Final Reports of the Ten Working Groups. The Academic Planning and Budget Committee used these reports – which included studies by committees on undergraduate education (subcommittees on admissions, financial aid, and advising/retention), Ph.D. education, professional education, international dimensions, faculty development, research, and the academic information environment – in order to develop a new five year plan.

The five year plan, entitled Planning for the ’90s, was introduced to the Trustees on 25 January 1991. The beginning of the plan identified a number of key concerns: University administration and leadership; research capacity; undergraduate, Ph.D. and professional education, the information environment, Penn’s role as an international university, and the quality of the campus environment. While the document requested each school and resource center to update and recast their own plans, it also detailed some of its plans for general improvement at Penn. Some of the most significant of those plans included proposals for physical plant growth and improved research facilities. The plan also specifically offered suggestions for improving areas of the Penn education, earlier identified as key concerns. In the most general sense, Planning for the 90s sought to diversify and make the educational opportunities offered by the University more unique.

Hackney’s most significant contribution to physical plant development was his plan to diversify Locust Walk. He announced a task force for the initiative in April 1990, naming Drs. Kim Morrisson and David Pope as co-chairs. Hackney considered the state of Locust Walk to be so important because, as the physical nucleus of the campus, it held a great deal of symbolic significance. Diversifying Locust Walk would allow the physical atmosphere of the campus to match the University’s commitment to its heterogeneous population. The task force released Report of the Committee to Diversify Locust Walk in September 1991. In the Report the task force identified seven objectives for Locust Walk:

- To welcome the entire University community on an equal footing

- To spread the intensity of its use as the center of the campus

- To create a mix of academic, residential, and administrative space in order to enrich the community

- To match the scale of construction between 36th and 37th streets

- To create newly renovated residential sites

- To create a residential community characterized by diversity, living in conjunction with learning, high standards of behavior, outreach and social activity, and undergraduate and graduate interaction and activity

- To make the opportunity to live on the Walk both a right and a privilege

The report also described: the charge to the committee; committee process and solicitation of opinion; Locust Walk’s physical aspects, Locust Walk in the context of campus planning; options for diversification; the conceptual plan developed by the Venturi, Scott Brown architectural study; programs and activities for promoting diversification; behavior on Locust Walk; ways to achieve a more variegated student culture on Locust Walk; and a timetable. Central to the report was the status of the group of traditionally white, male fraternities that dominated the Walk. Dissenting opinion on forcing those organizations to relocate imbued the entire report. Hackney ultimately decided not to force the fraternities to relocate. Today Locust Walk is the hub of the Penn campus, and while not all of the Committee’s plans for expansion and diversification have come to fruition, the Walk is a much more open and accepting place to be.

The diversification of Locust Walk reflected an even larger plan to firmly establish minority permanence at Penn. In January 1991 the Hackney administration set aside $35 million from the Campaign for Penn for the promotion of minority permanence. Penn’s commitment to minority representation on campus stemmed as far back as Meyerson’s Task Force on Black Presence. Since March 1978 the University had continuously worked to attract minority staff, students, and faculty. By June 1993 an Ad Hoc Minority Permanence Retrospective Review Committee set up by Hackney produced, Minority Permanence at the University of Pennsylvania: A Retrospective Analysis. This Analysis reviewed previous efforts made by the University to facilitate an increase in minority presence in five major areas:

- Faculty

- Afro-American Studies/li>

- Graduate/Professional Students/li>

- Undergraduates/li>

- General Academic and Support Services/li>

Not only did the Committee report on Penn’s successes, but it also advanced nine major outstanding and/or unresolved commitments:

- Establishing additional departmental incentives for recruiting minority faculty and scholars

- Retention of the Faculty Investment Fund for new African American faculty

- Funding for three to five full-time faculty and five to ten part-time faculty for the African Studies program in addition to two full time faculty for the Center for the Study of Black Literature and a distinguished chair in Afro-American studies

- Establishing a minority graduate center

- Establishing a supportive service network in each undergraduate school

- Establishing a Provost’s Financial Aid Fund for gifted minority students

- Establishing a continuous review of the Task Force on Black Presence (see Meyerson)

- Meeting central and school-based fundraising objectives

- Implementation of proposals relating to current racial awareness programs

The Retrospective Analysis determined that while the University had done quite a bit to increase the school’s minority presence, particularly by way of Affirmative Action programs, it still had a long way to go in order to better integrate the minority population. Hackney’s commitment to revising minority-related policies helped to pave the way for improved campus unity.

The Hackney administration did a great deal for the development of the University. Hackney’s constant revision of his educational plans proved that he truly wanted to “Choose Penn’s Future.” His Campaign for Penn, also incredibly important, became one of the largest fundraising drives ever attempted by an American university. The success of the Campaign for Penn allowed future administrators to outline even more ambitious plans for educational reform and physical expansion. Without the efforts of Sheldon Hackney, the University of Pennsylvania would not be the caliber of school it is today.