On June 28, 1914, a “shot was heard around the world.” The Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a Serb, and the “War to End All Wars” began. As the war began on the continent, in Europe, America, pursuing an isolationist policy until 1917, did not deign to enter into the fighting. This, of course, did not mean that the people in the United States were not concerned with events abroad.

Early support of the war from the Penn community

The Penn campus was becoming involved in World War I long before America officially did. Most of the faculty and staff of Penn who had been abroad that summer of 1914 returned to America. Some did not. Paul P. Cret, a Professor of Design, and Leon-Eugene Arnal, an Assistant Professor of Design, joined the French army. Arnal became a lieutenant, and Cret was a private. But not all joined on the side of the Entente. Walter Fischer, an instructor in French, entered the German Army as a reserve lieutenant; Frederick Maria Urban, an Assistant Professor of Psychology, entered the Austrian army, and Viktor Emil Sabary, who was an Instructor in German, entered the Adrian Army. On December 22, 1914, Penn released word that Dr. Arno Poebel of the University Museum, was assumed killed in action. He had entered the war as a reservist in the Breslau Corps of the German army, which had apparently been fighting on both the Western and the Eastern Fronts. This proved to be incorrect; Poebel survived the war and went on to teach at the University of Chicago. Penn individuals fighting in armies were not, though, the only relation the Penn campus had to the world at war.

Penn's medical contributions

On November 3rd, 1914, in a dispatch from Paris, it was learned that Dr. Hunter W. Scarlett, who was a graduate of Penn’s Medical School (1911) had, along with a Frenchman by the last name of des Jardins in the American Ambulance Service, discovered a microbe which had caused gangrene to develop in bullet and shrapnel wounds. The goal of the discovery immediately became to create a serum for patients on the battlefield to be injected so as to prevent unnecessary amputations and death. The work on the serum began in the Pasteur institute. This seems to be the first example of the Penn Medical School with relation to the Great War, and it certainly was not the last.

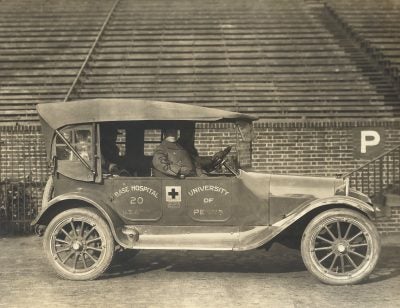

In January 1915, under the Chairmanship of Dr. J. William White, a graduate of Penn and a former surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital Philadelphia, men and women endowed a ward of forty beds at the American Ambulance Hospital in Paris. Sir William Osler, who had formerly been connected to the University of Pennsylvania stated that it “[was] the best equipped war hospital in Europe.” Also, in summer 1915, White and number of physicians, surgeons and nurses from the Penn staff were to go to the American Ambulance Service in Paris. This would be for a span of three months, as another college had completed the task three months prior. By the time America had entered the war, before June 1917, forty percent of the Penn Medical faculty had enlisted in the service. The University of Pennsylvania also had organized three ambulance units, a base hospital and several Red Cross and various detached units. Two hundred and fifty beds of the hospital were given over for special use by the Army and Navy.

Campus support for America's neutrality

A peace movement at Penn began in 1915, and a student organization developed, adopting officers and a constitution; they were called “The University of Pennsylvania Peace League to Combat Militarism.” The peace league students wanted to see the American flag as a symbol of peace and harmony for the world. The students at Penn wanted America to lead the peace example, and hoped that the world would follow. A petition was signed by several hundred Penn students and sent to the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, in May, 1915, with the expressed desire for the president to protect American neutrality. Nonetheless, there were some Penn students preparing for war long before it broke out – in 1916 there were many at the Plattsburg camps, and there were some engaged in fighting abroad. Two former Penn students who had gone abroad to Britain as Rhodes Scholars, and who attended Christ College, had joined the British forces; and a third was a Penn sportsman, A. N. S. Jackson. He became a lieutenant in the British 13th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade.

Penn mobilizes on a large scale as America enters the war

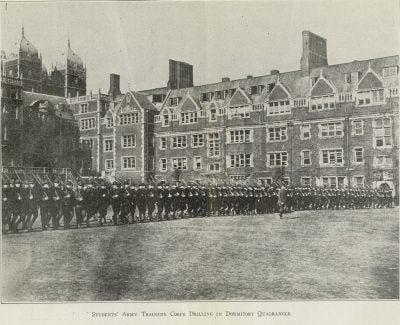

As it became apparent that America would enter the war, the campus became more militarized. A volunteer student battalion was formed and drilled. The picture at the top of this page shows Penn students doing drill on the quad of the Penn campus. Special training programs had been developed for the government and aviation and other examinations were taken on the Penn campus. The University of Pennsylvania even began a new four-year program in Military Science near the end of the war.

When the United States didenter the war, with a declaration from Congress on April 6, 1917, the population of Penn students and alumni answered the call. In the 1916-1917 academic year, 9,000 students had attended the University of Pennsylvania. In the fall of 1917, there were approximately 7,000 students on campus. About 2,000 students had enlisted in the military or joined a Government service at home or abroad. This number grew when Penn alumni were taken into account, with records showing that as of Commencement Exercises in June 1918, there were 6,102 Penn students and alumni in the U.S. service (including foreign armies and government service), with the majority in the Army. Approximately fifty had been reported dead, wounded or missing. In 1932, General Emilie Adolphe Taufflieb, who had commanded the 69th Division of the French Army during the defense of Verdun, handed the Medaille Verdun to Josiah H. Penniman, Penn’s Provost, in recognition of the services of University of Pennsylvania men during World War I. A picture of the presentation of the medal is shown to the left.The death of Europe's finest leads to a new role for Penn

Penn, though, took on another mission as it opened its doors in the fall of 1917. Recorder of the University, George E. Nitzsche described this new role for the University when he stated that,

“One of the greatest and saddest calamities already obvious as a lamentable result of the war, for European nations is that the intellectual flower of their population is being destroyed. A great swath of destruction has been cut through the ranks of educated young men who were to form the intellectual leaders of the coming generation. They are gone. The world has lost them. And those nations in the coming years will be so much the weaker and less progressive, less able to master the future’s problems. It is for us to take warning… We must keep the ranks of our educated men filled.”

Nitzsche’s words rang true; the Archbishop of York, while visiting Penn in March 1918 had stated in a speech that 2,081 men from Oxford and 2,050 men from Cambridge had been killed in the war. The loss of the new generation of educators in Europe was to be filled by American universities, and only through their acts, could the world progress. Global progress was now to rest on America’s shoulders, and the University of Pennsylvania answered the call.