Overview of Penn's contributions to the war effort

Penn’s involvement in World War II is extensive and well-documented. Two of the many documents chronicling this involvement can be viewed online: The University in War (1942) and This is our Crucial Year (1944), both published by the University.

Almost every school of the university was engaged in activities to aid the war effort, if not all of them; and 17,000 members of the Penn family, comprising students, alumni, faculty and staff, were in the armed forces. Of that number, three hundred and sixty-two died in the service of the country. This does not include those men, numbering about 10,000, sent to Penn to be trained for the Army, the Navy and the Coast Guard. This also does not include special programs carried out by the School of Nursing, the Moore School of Engineering and the University Hospital. This does not mention the research projects numbering over a hundred requested by the government related to the war and those projects which involved members of the Penn family away from the campus, namely, research on “radar, the atomic bomb, and sub-surface warfare.” University family members were chairmen on the War Labor Board and the Committee on Medical Research of the United States Office of Scientific Research Development. Over twenty-five thousand industrial workers took courses during the war years at the University in the Engineering, Science and Management War Training Program. In 1943, although the war would not yet end for two years, faculty at Penn, working with other superior faculty at other American universities and colleges began discussions on what the post-war period would bring, and how to act toward the defeated nations. But the story of Penn’s engagement with the crisis begins at least four months before the German Army invaded Poland on the first of September, 1939.

Early stages of the war effort

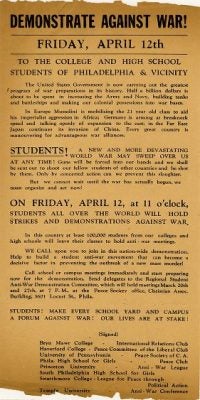

It is not surprising that the United States was concerned about affairs in Europe before war was officially declared. Germany, a nation pained by the harsh punishments it had to bear after World War I and incited to mobilization under Hitler’s regime, had already taken pieces of Europe back into German control with little resistance from Allied diplomacy, or so it seemed. German activities were blatant, and it was obvious war was brewing. The only question was when it would officially begin.At Penn, at the beginning of May 1939, the R.O.T.C. seriously began physical testing of its members on the campus. At the University Health Center, the Army Air Corps recruited students from Penn and Drexel, conducting physical examinations. Those students were expected to sign-up at Randolph Field (the air force base in Universal City, Texas) during the summer months. Initially, when the war did break out in Western Europe, some Penn students, along with students at other institutions demonstrated against it (the poster for a demonstration is shown to the left). The students at Penn were also concerned about the ramifications of America’s eventual entrance into the war and how it would affect their studies. On December 13, 1940, the Honorable Robert P. Patterson, then the Assistant Secretary of War delivered an address to the Wharton School, on this very issue.

Prior to Patterson’s visit, though, the University of Pennsylvania President, Thomas S. Gates (pictured above) had written in June 1940 to the Advisory Commission of the United States Council of National Defense. He wrote that:

In the development of the program which has been undertaken by the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense of the United States, it may be that the resources of educational institutions and educational activities will need to be explored or consideration given to their usefulness in the program as it eventuates.

Accordingly, we should be pleased to place at your disposal, and at the disposal of the Commission, the forces of the University of Pennsylvania to be used in such manner and for such purposes as may be appropriate.

May I also personally add the hope that if, in any way, in the slightest degree, the Commission feels that any cooperation on my part or on the part of other officials of the University will be helpful, you will call upon us.

The Penn president had volunteered the services of the University to the government for the war. Throughout that summer, communications via telegram were made to the War and Navy Departments. The University of Pennsylvania also created its own Committee on National Defense, though the name would later be changed to “The University of Pennsylvania War Council.”

Penn's contributions to the war effort after Pearl Harbor

After the attack on Pearl Harbor there was no question of doubt in the American mind of how the nation would respond, and the members of the Penn family entered the service in the thousands. Even in those first days after the attack, Penn was involved in the war effort. In the Hawaiian islands, those needing medical attention were diligently served by Penn alumni. Those alumni included: Colonel Smock from the class of 1912, Commander Brunson at the Pearl Harbor Naval Hospital from the class of 1918, Colonel Canning from medical class of 1910, Captain Ryan, who was Chief of the Surgical Service at Pearl Harbor Naval Hospital from the graduate school of medicine class of 1926, as well as civilian surgeons who were graduates of the Penn medical school. Two Penn alumni were at the Letterman General Hospital of the Army in Presidio, San Francisco, California as well as one at Mare Island Naval Hospital, City of Vallejo, Northern California.

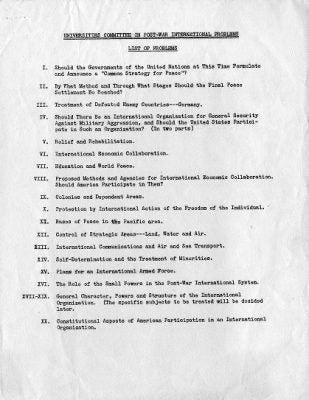

By 1943, multiple training programs had been set up at the school, as already mentioned at the beginning of this section. There was also a training program for the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) at the Moore School, designed to train them for work in the Ballistic Research Laboratory. That program ran for thirty-two weeks and the women completed forty hours of training each week. Also, at this time, as previously mentioned, a committee was appointed at the University of Pennsylvania on Post-War International Problems. It was chaired by Dr. Edwin B. Williams, then the Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and at one point, the future director of the Office for Foreign Students, William Rex Crawford was a member. As stated before, this committee worked with other such committees at other institutions, and the entire project was led by a committee at Harvard. The information, received from the various institutions and combined into one report by that committee was to be published for both the government and the public. The list of problems, twenty of them to be precise, the committee at Penn was to review (shown at left). A second committee, headed by Dr. Edwin R. Keedy, then the Dean of the University’s Law School was created to deal with the problems the University would encounter after the war would end, and how the University itself could actively engage the world to help it out of the post-war period as best it could.The security of the current members of the University and the grounds were also of high concern. The University had an Air Raid Warden Unit, involving six hundred and thirty-four people trained for emergency situations. The University had purchased equipment in the event of an air raid emergency, costing $15,000. The University also had a number of first aid stations on Campus, and this did not include either the Student Health Service or the University Hospital. Valuable records and artifacts of the university were kept in secure locations for the duration of the War.

As for the R.O.T.C. on campus, it had been established during World War I, had added a medical unit, and had been active on campus during the years between the wars. In 1940, the United States Navy Department selected Penn to train Naval Reserve Officers. Penn was one of eight schools across the nation which would do so. This is in addition to the pre-existing, at that time, course of study in the Department of Naval Science and Tactics. Perhaps the largest program, though, was the one for the Engineering, Science and Management Defense Training (ESMDT). By 1942, 4,000 people had already completed courses at Penn, and more continued after that date. The Penn University Hospital, with a history of service in both the Spanish-American War of 1898 and World War I, continued their efforts in World War II both at home and abroad. The United States Army 20th General Hospital from the University of Pennsylvania served abroad in Burma, India during the War, aiding in preserving the lines of communication between American, British and Chinese troops fighting the Japanese there. The executive officer of this base of operations was Dr. Isidor S. Ravdin (pictured below at his desk in India, 1945).

By the middle of the United States’ period of involvement in World War II, enrollment had suffered greatly at American institutions of higher education. The University of Pennsylvania was no exception. The average enrollment before the war years at Penn was 17,000 students. Of those 17,000 students, 12,000 were male. Many of the male students at Penn, while continuing their studies were training for the Army and the Navy. By the 1943-1944 academic year, however, according to an official University report, if one were to exclude those students engaged in the aforementioned training, the number of male students enrolled at Penn was 2,800. The enrollment of female students experienced a decrease as well. Because of these numbers, the University of Pennsylvania experienced a large deficit, which amounted to a sum of $300,000. In today’s world, that deficit would be $3.5 million. The government and military training services the University had provided were not the cause of the deficit – the government paid for those. In fact, it was recognized at one point that the deficit problem had been relieved by the fact that the campus was being used by the government and military as they were. But as the war came to a close, the need for such programs by the government was diminished, and Penn could no longer rely on this source of income. The creation of accelerated programs for all undergraduate courses of study and many professional degrees, allowing students to complete their degrees before going into active service, may have contributed to the deficit as well. Under these programs, students completed their courses of study in two and a half years instead of four.

Around that same time, the University of Pennsylvania Navy V-12 Unit (a type of unit established on university campuses by the War Department to provide a supply of officers) was awarded the Commandant’s Pennant due to the high amount of War Savings Bonds that had been purchased. The Rear Admiral of the U.S. Navy from the Fourth Naval District in Philadelphia wrote in a letter to Captain L. M. Stevens, who was the commanding officer of the unit at Penn, that he commended the Penn men in the unit, and “their evidence of demonstrating that a country worth fighting for is worth investing in.”

During the war years, Penn also trained service men in foreign languages that were deemed necessary for the effort. These included studies in Moroccan Arabic, Chinese, Bengali, Hindustani, Russian, German, Spanish and Portuguese. When some service men began to return home from exotic locations, the City of Philadelphia, along with other cities across the nation, became concerned that those who had suffered and recovered from malaria contracted in areas of the world such as Asia, the Mediterranean and Africa could possibly bring a malaria epidemic upon the city. Though the exact threat of that nature was highly unlikely, students at Penn continued efforts in parasitology courses. Also, in February 1945, the Security Shield of Honor was awarded to the University of Pennsylvania for its contributions to the Port Security Program of the United States Coast Guard. The hospital staff of the 20th General Hospital (mentioned above) would also receive a pennant, but this award was given to them by the Chinese general Li-Jen Sun. An excerpt from the citation reads, “[a]t the close of the Campaign, we take pleasure in presenting to you a pennant as an expression of our sincere gratitude for your service and as a souvenir of our intimate cooperation.”

War's end

On the eighth of May, 1945, the war in Europe officially ended. Penn celebrated with chapel services in Irvine Auditorium. The ushers for this were thirty veterans of the war and Dr. Gates spoke. The University of Pennsylvania Service of Thanksgiving and Rededication was led by the Chaplain of the University, Dr. J. Clemens Kolb. But although the War in Europe had ended, the War with Japan continued until the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945.

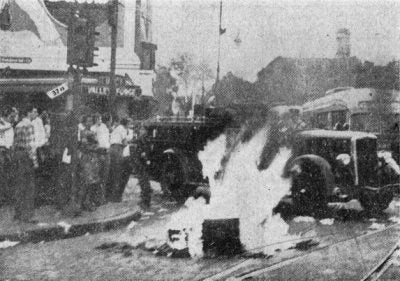

Upon President Truman’s announcement of V-J Day, the University of Pennsylvania broke into celebration. Though the academic year had not yet started, the summer students and some faculty and staff blockaded 37th Street and Woodland Avenue for two hours demonstrating, halted all automobiles, and pulled the trolley poles from their wires, effectively stopping all traffic. Many of the passengers of the trolley car which had been halted in its journey joined in the demonstrating as a bonfire was lit on the trolley tracks (pictured below). Overhead, the V-12 students who had been confined to their dormitories (they had gotten out of hand while celebrating the previous Sunday after a false notification of Japanese surrender), looked on to the people in the streets. Eventually, the police arrived on the scene, and arrested two men, one, Dr. Philip Goland of the Medical School faculty, and the other a veteran of the war, Clifford Maynard who had begun studies at the University, charging them with disrupting the peace and inciting the riot. The two men, as the story goes, claimed that the police were about to begin spraying water on the crowd to break up the demonstration. At any rate, the newspapers of Philadelphia reported on the sheer ecstatic nature of the crowds throughout the city celebrating the end of the war.

In a more somber tone, peace services were also conducted at Penn. The School of Nursing of the University of Pennsylvania was in a chapel service in Irvine Auditorium singing in a chorus (pictured below).

The chaplain of the University, the Rev. J. Clemens Kolb (mentioned earlier) conducted the Philadelphia service honoring the American Red Cross. A Service of Thanksgiving for Victory in Irvine Auditorium that was held on Friday, August 17, 1945, presented an Honor Roll in the program which listed those former Penn students who had died in World War II. The cover of the September 1945 issue of the Penn Gazette featured a Tribute to War Dead, with the picture of a wreath being laid in the front of a memorial (pictured below). That World War II memorial can be found today at the entrance to the Furness Building. A list of Penn’s fallen was included in the program for a service of commemoration held on May 30, 1946.