The history of the University of Pennsylvania’s engagement with Africa can be clearly seen in three locations with which it has had relations: Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa. Beyond these three, Penn has had relations with other countries, but not to the scale as the aforementioned. Some of these are examined in the earlier section of this report on study abroad in Africa. Those will not be repeated here. The relations which were not mentioned in that earlier section are examined at the end of this section of the report. It is important to note that a few African Penn graduates would go on to important positions in Africa; Kwame Nkrumah, having graduated Penn with two Master’s degrees in 1942 and 1943 became the President of Ghana from 1960 to 1966. Alassane D. Ouattara, who earned his doctorate at Penn was the Prime Minister of the Ivory Coast from 1990 to 1993. And mentioned again later in this section is Nnamdi Azikiwe, who graduated with his Master’s degree in 1993. He would become the President of Nigeria from 1963 to 1966.

Egypt

Between 1915 and 1923, the Penn University Museum had worked at excavation sites in Memphis, Giza, Denderah and Thebes, and in 1932, its staff worked in Meydum for three years. This type of work resumed in February 1954. A dig in Memphis exploring the Temple of Ptah saw the Penn Museum under the leadership of Dr. Forelich G. Rainey, its director and the Egyptian Department of Antiquities working together. According to Rainey, not long after World War II, road-builders had accidentally discovered the site they were to work at; although the main Temple had been an excavation site previously, they were to work on the southwest corner of the temple area where the road-builders had made their discovery. This work was the first done at this specific site. Dr. Rudolf Anthes was the field director, then the curator of the Egyptian Section of the University Museum (previously he had been director at the Egyptian Museum at Berlin, Germany), and he had at least two others from Penn assisting him: Dr. Henry G. Fischer, the assistant curator, and John M. Dimick, also on the museum staff at the time. Dr. Anthes was reported as conveying his enthusiasm at working with Egyptian archaeologists. He stated, “By means of this cooperation we hope to advance the mutual understanding between Egyptians and Americans.”

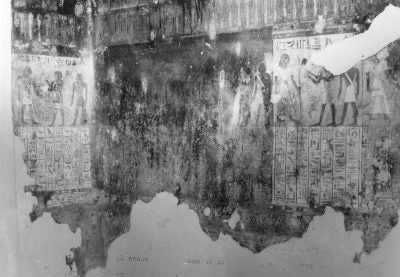

In 1973, Lanny Bell led an archaeological team to a discovery of the tomb of Nebwenenef, the high priest of Amun followed by another tomb – the one of Bekenkohns, also a high priest of Amun. Penn archaeologists worked on the long process of clearing away debris and cleaning the sites – two panels of a funerary scene from Bekenkohns’ tomb were pieced together and displayed (shown at right). Expeditions in Memphis, Egypt, were certainly underway that year (shown below).

The next year, the Van Pelt Library displayed two special exhibits titled “Napoleon’s Egypt,” having borrowed artifacts from the University Museum. Napoleon’s expedition into Egypt in 1798 is best known for having discovered the Rosetta Stone. Also displayed was a set of books published by the French Government around that same time. A couple of years later, in 1976, a University of Pennsylvania team, led by Prof. Donald B. Redford, discovered the foundations of a wall that was part of the temple Gem-Pa-Aton. He was leading the team as part of the Ikhnaton Temple Project, which had begun at the University of Pennsylvania ten years prior in 1966. Ray W. Smith, an American scholar had suggested the project to Penn based on the discoveries of building blocks found over the course of a century at other sites.

Three years later, in 1979, an Egyptian exhibit, called “The Search for Ancient Egypt” opened at the Penn Museum, funded by the University of Pennsylvania and a $41,000 grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH). This marked the first time that Egyptian artifacts belonging to the Museum were put on display. Penn had acquired some of the artifacts as early as 1890. It was an especially good time to create the exhibit as the interest in Egyptian history had grown due to the opening of the Tutankhamun exhibit in New York not too much earlier. The exhibit was co-directed by two assistant curators of the Penn Museum, David Silverman and David O’Connor. Most of the exhibit contained displays of artifacts directly from Penn excavations. Four thousand years of Egyptian history were examined in the various displays. When the exhibit opened, Martin Biddle, then the museum director, and Abdullah Fouad Hafez, then the Egyptian consul general “touch[ed] an adze (ax) to the lips of the statue Sarhmet.” They made a similar gesture on the giant head of Ramses II later on. (pictured below).

Nigeria

Although the previous section of this report examines Penn’s work with the University of Ibadan in the late 1980s and early 1990s, this was not the only time when Penn had relations with this country. In 1963, Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell sent a cablegram to Nigeria congratulating the University of Nigeria on its first graduating class of 149 students. The founder of that university, Nnamdi Azikiwe, then the Governor-General of Nigeria, had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1933 with a Master’s degree in anthropology. Harnwell’s cablegram reads as follows:

The University of Pennsylvania salutes the University of Nigeria upon the occasion of its first convocation. The significant ceremony in which Pennsylvania is honored to participate through these greetings celebrates a milestone in the vital life of your country. It is of particular import to Pennsylvania since the University’s founder and Governor General of Nigeria, Nnamdi Azikiwe, is one of our institution’s most distinguished graduates. We wish the University of Nigeria, the members of its first graduating class, and the participants in its community a long and distinguished future in the service of Nigeria.

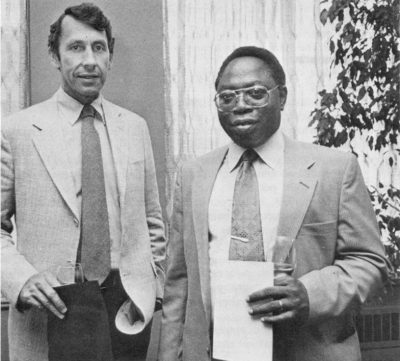

Penn’s interest with the University of Ibadan (UI) began in the 1973-1974 academic year when Prof. Robert Rutman from Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine visited Ibadan. This was responded to by the visit of Nigerian educators to the Penn campus in 1981. A linkage agreement had been signed between Penn and the University of Ibadan. Humphrey Tonkin, then the Director of International Programs at Penn stated that “[t]his is the most comprehensive agreement that we know of between a university in the United States and a university in black Africa. We have involved almost every school in the University. Our interdisciplinary programs lend themselves to this kind of effort.” In November, Penn President F. Sheldon Hackney went flew to Nigeria to “give a strong send-off to the University’s exchange.” Earlier that year, Prof. S. Olajuwon Olayide, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Ibadan and the chief operative officer of UI, came to Penn and delivered a lecture. Work between Penn and Ibadan continued from the work of Hackney and Olayide (picture at below) and more information can be found on this work in the section on study abroad already mentioned.

Penn and South Africa: The Issue of Divestment

In the 1980s, the issue of universities investing in companies who did business in apartheid South Africa swept the nation. Penn was not immune. Although Penn’s investments in companies in South Africa did not reach the amount of some other institutions, such as Harvard University, it was still a large amount. During this time, many of the members of the Penn family rose up against the Penn Board of Trustees who did not move to, at least for some time, divest from companies that were involved in South Africa. It was thought that Penn had, by unwittingly funding those companies along with many other institutions, indirectly funded the apartheid South African government. This called into play, yet again, that controversial issue of institutional morals which had dominated the arguments surrounding Penn’s relationship with Iran in the 1970s and those surrounding Penn’s involvement with the government during the Vietnam War. Being much more recent history, though, one is very careful to present everything in as objective a light as possible and conveying a purely historical sense in examining the history of the University of Pennsylvania’s struggle with the South African Divestment.

As early as January 1980, some of the students at the Penn campus were protesting for the Penn Board of Trustees to divest of its holdings in the companies doing business in South Africa. The issue was given impetus by news that erupted against First Pennsylvania, the bank with which the University of Pennsylvania worked. First Pennsylvania at the time “over[saw] all of the University’s operating accounts and in which the University own[ed] roughly one million dollars and in stocks and convertible debentures.” Apparently, the First Pennsylvania bank had in the past cooperated with Space Research Cooperation, giving them a $2.2 million loan in June 1976. The money apparently enabled that Cooperation to buy “53,000 rough steel forgings, which were then converted into 155mm howitzer shells and sold to South Africa. The shells, along with an assortment of military technologies were delivered to South Africa between 1976 and 1978 in a deal worth an estimated $50 million.” In 1980, although a grand jury investigation was progressing, the spark had already been caught. The story in people’s minds read as follows: the University of Pennsylvania works with a bank who invested in a Corporation that bough items that eventually led to the manufacturing of a large deal of weapons in South Africa. Although the relation of Penn to South Africa here was obviously quite indirect, it captured enough attention for members of the Penn family to look at other financial relationships Penn had with companies who also were happening to do business in South Africa. The timing could not have been better to provoke unrest; other members of other institutional families were doing the same to their own institutions, especially as people became more aware of the crimes of the Apartheid South African Government. The fight for South African divestment had begun at Penn.

Penn President F. Sheldon Hackney was inaugurated into office at the same time when the events on the Penn campus surrounding the controversy over divestment really began to cook. In fact, a symposium on divestment featuring the South African Journalist (who had founded the Union of Black Journalists), Dumisami S. Kumali, was held on October 21st in direct connection to campus events surrounding Hackney’s inauguration on the 23rd.

Earlier in 1981, a faculty-student committee had been formed to investigate “the University’s policy on investments in South Africa.” A divestment coalition was formed later in that fall semester by students by members of three university organizations: the Black Student League, the Progressive Student Alliance and the Undergraduate Assembly. The University Council Committee on South Africa Forum on October 26, 1981 ended in what the Daily Pennsylvanian called a “frenzy.” The audience appeared to be against the Sullivan Principles, a list of regulations designed originally in 1977 to end racial discrimination and segregation at the workplace. This would directly contradict the system put in place in South Africa by its apartheid government. If companies doing business in South Africa adhered to the Sullivan Principles, then it would be deemed alright for people to invest in those specific companies.

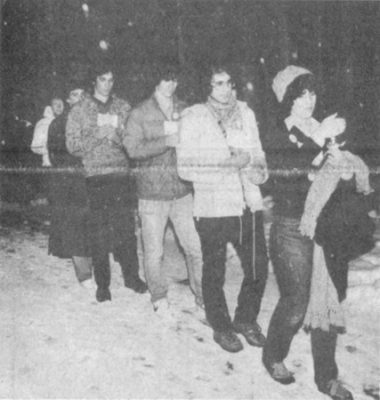

The Penn Coalition for Divestment, under the co-Chairman Maureen Anderson, held a candlelight vigil (pictured below) with about fifty students that same month. The vigil had been sponsored to “mourn for the political prisoners killed while in the custody of South African policy, and to pray for future South African activists…” A student also reported, though, that recognizing divestment didn’t mean that apartheid would end. In November 1982, Theo Vorster, the South African consul for information was to appear on the Penn campus. He cancelled his visit one day prior to the event when it was apparent that his appearance would spark a large amount of protest. Apparently, “[t]he union cancelled Vorster’s visit when it reportedly felt that, with groups outside the University said to be joining the protest, it had reason to fear for Vorster’s safety.” However, Penn Provost Thomas Ehrlich was evidently dismayed that although the University did not support the institution of apartheid government, students should have had the opportunity to listen to a speaker and debate the issue.

By February 1983, the United Minorities Council had condemned the Penn Board of Trustees for not divesting. Penn Board of Trustee member, A. Leon Higginbotham was apparently of the opinion that if Penn continued to invest in companies doing business in Africa and was able to exert influence over their actions, influence could be exerted that could lead to the end of apartheid. He stated that the University’s investments were part of a “dialogue and pressure for change.” This was not accepted by the Council. At this point, the University of Pennsylvania still had $28 million invested in companies in South Africa. The issue continued to cook over the next years. By 1985, it seemed that it had reached a breaking point, regardless of the fact that Penn President Hackney spoke as a private citizen before a United States Senate Committee that the Government of the United States needed to act to convince the South African Government to end apartheid.

The Graduate and Professional Students Assembly (GAPSA) unanimously called for divestment in October 1985. Penn also decided to divest from those companies in South Africa that it had been doing business with which were not upholding the Sullivan Principles. These included Dart & Kraft Inc., in which the University held $800,000 stock. However, in comparison with some other nearby universities, it seemed a small effort. That same month, it was announced that Temple University had divested $2.75 million of stock in nineteen companies. Columbia University followed this action five days later by selling $39 million of South Africa-related holdings, making it the first Ivy League school to do so. Unless apartheid ended by June 1987, Bryn Mawr College would do the same. Penn did not follow suit with Columbia, though. Students protested outside another meeting of the Board of Trustees and demanded that Penn divest of its South Africa-related holdings, which in one report stated were $68.7 million in stocks and $23.1 million in bonds. In comparison, Harvard University followed a policy at the time of “selected divestiture,” divesting in those companies which refused to comply with the Sullivan Principles. At the time, it was also reported that Harvard University had $400 million in ninety companies in South Africa-related holdings. It was made apparent as well at the time by the Investors Responsibility Research Center in Washington, that complete divestment could have severe repercussions for those schools with such a large amount of money at stake. If an institution were to divest completely and make a South Africa-free portfolio, they would be agreeing to “never again hold stock in thirty of the world’s fifty largest corporations.”

In late October 1985, another rally was held outside a Board of Trustees meeting. This time, more than two hundred and fifty students appeared (pictured below). This rally, occurring on a Friday, ended a vigil which had begun on Wednesday at College Hall and had been round-the-clock by the Penn Anti-Apartheid Coalition. David Richardson, a Pennsylvania State Representative, spoke at the rally wondering with admiration at the audience’s “hearts and guts, to tell this country to get the hell out of South Africa.”

On January 15, Nobel Peace Prize winner Bishop Desmond Tutu delivered the University’s Martin Luther King Memorial Address. He did not speak on divestment, though he knew that the Board of Trustees was scheduled to begin discussions on divestment the next day. But speaking at Penn’s W.E.B. DuBois House to about one hundred and fifty students and other people, Tutu expressed his concerns about President Reagan’s action to not push any other economic sanctions on the South African Government. But he did state: “I feel a tremendous outpouring of love and support from the Penn student body.” Meanwhile, his wife, Leah Tutu spoke at the anti-apartheid rally on the College Hall Green. Nevertheless, the Trustees on January 17 resolved to wait another eighteen months, at which point they would consider divestment.

Protest continued. Three South African students in late January had a sit-in Penn President Hackney’s office, though this action was against the University’s Guidelines on Open Expression. A group of alumni, which called itself the Ad Hoc Penn Alumni for Divestment, put an ad in the paper urging the Penn Board of Trustees to move towards divestment. United States Congressman William Gray (pictured at right) attended a sit-in at College Hall. A twenty day sit-in occurred in February 1986 by the Penn Anti-Apartheid Coalition. Five Penn students and four Penn organizations even filed a lawsuit against the Penn Board of Trustees. The suit claimed that the Board of Trustees had violated the Pennsylvania Open Meeting Law and alleged that eleven of the trustees had “business ties to corporations that do business in or make loans to South Africa.”A small shanty appeared outside College Hall in April 1986. It was not the only one. The shantytown outside College Hall was named “Paul F. Millersville” (pictured below). Just as Hoovervilles during the Great Depression had been named for President Herbert Hoover, “Millersville” was named for the Chairman of the Penn Board of Trustees, Paul F. Miller. The Penn campus was not alone – some other college campuses featured shanties of their own. On April 9, 1986, yet another sit-in, the third, occurred in Penn President Hackney’s office. Protest groups showed up five days later at the Board of Trustees Executive Committee. As John Neff gave the Investment Board’s report, “thirty observers advocating the University’s total divestment rose from their seats and stood with backs to the committee.”

Finally, in June 1986, the Penn Board of Trustees passed a resolution putting a time limit on divestment. The deadline was June 30, 1988 for a company in South Africa in which the University invested in. By June 19, 1987, only three companies the University invested in did business in South Africa. They were Tenneco, Caterpillar and Boeing. They were to withdraw from South Africa. If they did not, the University would divest from them. By 1987, many of the other companies Penn had holdings in had already withdrawn from that country. Finally, as an end to the story, in late 1993, under request by South African President Nelson Mandela and United States President Bill Clinton, it was decided that American investment in South Africa could resume, and the Steering Committee recommended that the Board of Trustees would lift its own prohibition on investing in South Africa, which six years earlier it had sought to obtain. The vote was unanimous in favor of this action.

Penn and South Africa: Not Exclusively Divestment

In 1979, the Owen J. Roberts memorial Lecture at the University of Pennsylvania was given by Sydney Wolf Kentridge. Though a white South African lawyer, he was respected by many of the blacks in South Africa, after having represented the Stephen Biko family; Biko, a black leader, had died in a South African jail. He lectured at Penn on “The Pathology of a Legal System: Criminal Justice in South Africa.” That same year, Bay Sirmon, a graduate student at Penn was almost deported back to South Africa after having arrived in the United States for political asylum. In 1981, Prof. William W. Brickman returned to Penn after spending two months in South Africa visiting the University of Cape Town and other schools in that country.

More Penn links to Africa

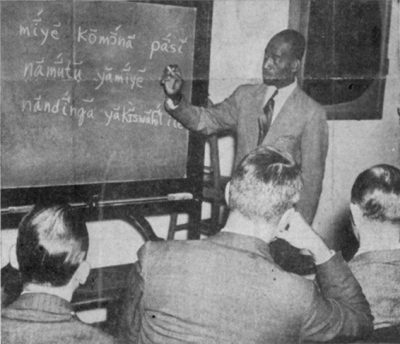

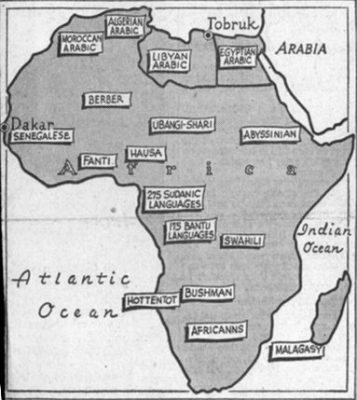

Native African languages were taught at Penn during World War II at the University Museum (pictured at right). In 1942, the curator of the African section of the University Museum at the time, Dr. Heinrich Albert Wieschoff, commented that “[i]t took a war to put African on the map.” University scholars recorded and codified languages making it possible to re-teach them, and the American Council of Learned Societies financed the effort. Similar efforts were being made at other college campuses. For example, Yale was working with Japanese, Malayan and Russian. Wieschoff let it be known that American universities were way behind Germany in this respect. He stated “The University of Berlin has five professors who teach nothing but Swahili. There are, in all, about twenty centers in Germany for African affairs, including a special school in colonial highway construction.” Penn was pushing to compete with Germany in African studies during the Second World War.

A faculty committee in 1960 was held to discuss the possibilities of an African Studies Program similar in form to the already existing Southeast Asia Studies Program. The next year, in 1961, in cooperation with United States President Kennedy’s Peace Corps Program, four Penn students were to teach in secondary schools in East Africa. Also in 1961, Penn and Lincoln University hosted one hundred African students that summer to prepare them for entry into some American colleges and universities. Speaking on this topic, William Rex Crawford, the former director of the Office for Foreign Students and director of the African Orientation Course stated that “[e]ducating Africans is “in the air” these days… In fact, competition between the U.S. and Russia to educate them almost amounts to “body-snatching” as college representatives scour the African continent in search of potential students.” Indeed, this preoccupation with beating the Russian education system became an article that September in TIME magazine. The African Orientation Program was sponsored by the International Co-operation Administration, the State Department, the African American Institute, the African Scholarship Program of 141 Colleges and Universities, the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), and other foundations and individuals. Later that year, a panel of five African students from different African nations spoke in a discussion called “Perceiving through African Eyes” in a series program on Sub-Saharan Africa. Dr. John F. Melby, Director of the Office for Foreign Students in 1961, cited the plight of African students in the United States as the following: “As far as anyone off-campus is concerned the African is just another Negro. When he goes into a barbershop he can’t get a haircut and when he goes into a restricted restaurant he won’t be served. If he tries to explain that he is a foreign student, the usual reply is “Yeh, you and who else?”” Melby concluded that the only thing occurring because of this was the resentment of black Africans being associated with African Americans.

Beginning in 1983, there were summer institutes in African Studies held at Penn on African culture and history. This was followed in the fall by the Wharton School hosting the “first known conference of U.S. and African academic, business and government figures designed to promote the private sector, and especially small business development, in Africa.” Congressman William Gray, mentioned above, attended, as well as many important African officials. There was a symposium on economic conditions and developments in Africa, and the whole effort was a portion of the Wharton-Africa Entrepreneurial Project.