Penn’s historical interaction with the Middle East in the twentieth century center predominantly around two nations of interest: Israel and Iran. Other countries and ethnic groups also figure in the history and will be examined briefly at the end of this section. Afghanistan is also included here, though it isn’t technically part of the Middle East.

Israel

Penn’s activity with Israel was strong in the 1970s and 1980s. Penn was notably involved during this period, both in affiliating with Israeli universities and in discussing internally the several Israeli conflicts.

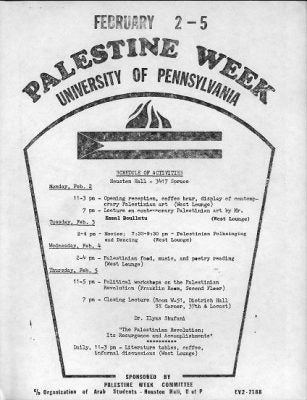

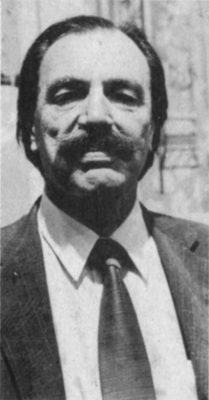

Since its creation in 1948, Israel has been in conflict with the Arabic peoples of the Middle East. These problems escalated after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. In 1971, Dr. Roger Allen, an Arabic professor at Penn debated with Dr. John T. Townsend of the Philadelphia Divinity school on the crisis in the Middle East. Three years later, in 1974, one hundred students gathered on the Penn campus to hear a lecture sponsored by the new Penn chapter of the national Zionist organization Hamagshimim, to hear an Israeli, Yitschak Ben Gad (Macluf), plea for Israel in its current crisis, the Palestinian conflict. Although the audience was mostly Jewish, there were some people representing the opposing side – fifteen representing the Palestinians, of which the group was not entirely ethnic Arab. It is not clear what kind of mark this event left on the Penn campus, if any at all, but it did represent the kind of action international diplomats should have been taking in the Middle East, and no doubt led to some form of greater understanding in the student body. Later that same year, in December, the Organization of Arab Students at the University of Pennsylvania sponsored a press conference in which Dr. Clovis Maksoud, a Lebanese journalist (pictured at left) stated that the purpose of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), in forming a “re-constituted Palestine” had hope. In fact, there was a “Palestine Week” (poster on the right) at Penn co-sponsored by the aforementioned organization, the Middle East Coordinating Committee, the Young Socialist Alliance, the Ethiopian Student Union and Palestine National Liberation Movement of America.In 1977, there was a lecture series at Penn titled “The Middle East: Geneva and Peace in 1977?” which was sponsored by the Middle East Center. The series would feature diplomats from all sides of the conflicts: from Israel itself, Egypt, Syria, the US, and in October, Palestine. On April 20, a minister of the Embassy of Israel to the United States, Hanan Bar-On lectured, followed the next day by the Ambassador at the Embassy of Egypt to the United States, Ashraf Gorbal, and on April 26 the Ambassador of the Syrian Delegation to the United Nations, Mowaffak Allaf spoke, followed in turn two days later by the Director of Intelligence and Research at the State Department, Harold H. Saunders. In October, Dr. Fayez Savegh spoke, who was a member of the Palestinian National Council and of the Kuwaiti mission to the United Nations. A Jordanian spokesperson lectured that November as well. In 1985, the Israeli Ambassador to the United Nations, Benjamin Netanyahu spoke at Penn, opposing the Arab position, though he did state rather directly that Israelis cannot have a purely Jewish-state – they would have to learn to live with minorities, namely, the Palestinians.

As for university affiliations, in 1974, the Penn-Israel university program began. At its fifth anniversary, Dr. Oler, the Director of the program stated that through it, “approximately forty members of the University faculty have worked in Israel,” and in an article appearing one month later, celebrating the same event, it was stated that “[t]o date, some fifty professors from Israel, whose fields encompass virtually the entire range of scholarship, have come to the University of Pennsylvania,” and that “there are more Israelis teaching at Penn at any given moment than at any other overseas institution.” In 1981, Penn awarded sixteen traveling grants (fourteen for undergraduates and two for graduates) for students to go to Israeli universities (Hebrew University or Bar Ilan University) or to take part in archaeological excavations: nine of the students went to Tel Gerisa (Tel Aviv) with this objective.

Penn President Sheldon Hackney received an honorary degree from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem on July 3, 1984; he went to Israel for eleven days that summer and met with leading officials in that country including Chaim Herzog, the President of Israel.

Iran

Although the University Museum had its first expedition to Iran in 1931, the majority of exchange between Penn and Iran took place in the 1960s and 1970s. The 1960s are prevalently positive, and Penn’s affiliation with Pahlavi University began in this decade and flourished. The 1970s, though, became more tumultuous, as the domestic politics within Iran worsened and the University had to deal with a situation (which they would have to deal with again in the 1980s with regard to South Africa) in which institutional morals, never an easy subject, were called into play.

In 1960, the University Museum at Penn hosted members of the Fourth International Congress of Persian Art and Archaeology for a luncheon in honor of the Iranian delegation to that congress. Also, the government of Iran loaned the University Museum objects for a museum display, including ones from the Hasanlu excavations. Two months later, the Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, invited Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell to come to Iran and examine Iran’s higher institutions. Harnwell prepared a report at the Shah’s request, entitled A Pattern for a New University in Iran, and it was decided that Penn would assist the Iranian government to transform Pahlavi University, which had its beginnings in 1946, into the only institution in the Middle East based on American-style higher education. The then American-fashioned University opened in 1962. By 1966, Pahlavi University had an enrollment of about 3,000 individuals and every year, Penn sent an advisory team to Iran. Before continuing with this story, though, a moment must be spared to report on a related occasion which occurred in April of 1962.

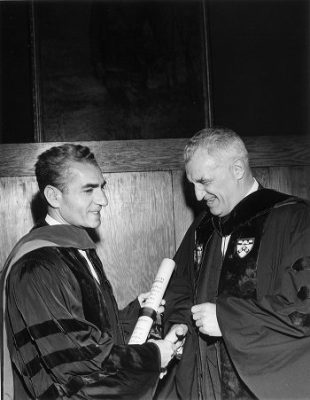

The Shah of Iran, in that year, visited the Penn campus. His helicopter landed in Franklin Field, (shown in the pictures to the right) and at a ceremony later, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Part of what the Shah said that day was recorded in an article released by the University of Pennsylvania News Bureau:

“With your continued interest in Iranian studies, I consider that we are fortunate to have the benefit of your counsel in our undertaking to build up the new Pahlavi University in Shiraz….The development of universities and the extension of popular education are among my overriding concerns…. We are confident that the fruitful cooperation between this distinguished center of learning and our newly conceived university will strengthen the bonds of friendship between my people and the people of this great country….I am convinced that there is no better way to preserve the peace of the world than by encouraging such cultural exchanges.”

By the mid-1970s, though, the situation began to change. In Iran, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was leading a dictatorial regime. Questions about United States involvement in Iran, especially with regards to the petroleum industries and gifts being given to figures of prominence caught the public eye. The Shah had given gifts to other American institutions, namely the University of Southern California in the form of an endowed chair of petroleum engineering and a million dollar donation to George Washington University to create an Iranian Studies program. Provost Vartan Gregorian was keenly aware that institutional relationships with Iran were arousing controversy. A couple of professors at Penn spoke rather frankly on the issue, and supposed that although it hadn’t been investigated, they would not be surprised if Penn had received some other wealth from its relationship with the Shah, considering the amount of oil revenues that that country’s government had.

Although reports of brutal incidents in that country and stories about the Iranian secret police grew steadily, the Iranian intellectuals supposedly felt protected from their own government due to American involvement in Iran. Pahlavi University was supposedly one of those protections. That same year, Penn President Martin Meyerson defended the project, stating that “Iran is a country not given to political and academic rights.” He felt that, as an institution, Penn should not involve itself in Iranian domestic politics outside of the scene of its affiliations. The idea that became known and which would be used again to defend Penn’s investments in South Africa in the 1980s was that using its influence in its affiliations, Penn could affect subtle change in society in whatever country it had dealings with. Through Penn’s involvement at Pahlavi, perhaps the situation in Iranian society could improve.

To some on the campus, though, this was a long shot. In a Letter to the Editor in a March 1977 issue of the Daily Pennsylvanian, Naomi Schneider, a member of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, stated

“[w]ould the United States establish exchange programs with Nazi Germany during the 1930’s in order to ‘subtly’ alter the cultural or political climate of the nation? Could a ‘professional challenge’ justify the establishment of a relationship with Hitler’s regime? I fail to see how any environmental program initiated in Iran could possibly change the political climate of the regime and be interpreted in any manner except as complicity with the Shah’s dictatorship. A boycott of any program with Iran is the only way to voice our opposition to the Shah.”

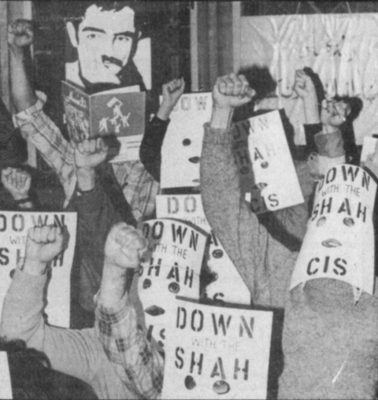

To clear up the exact relationship between Penn and Pahlavi University, the administration published the six-page contract which had been signed in 1971. However, this action did not help feelings on the campus much. A hunger strike was organized, and not soon after there were more protests against the dictatorial regime of the Shah (the picture at left is from April 1978), the remaining contract between Penn and Pahlavi expired in May and was not renewed.

However, events in Iran continued to affect the Penn campus. The situation in Iran changed in 1979, with the Islamic Revolution: the Shah went into exile. While the Shah was receiving medical treatment in the United States under the Carter administration, the Iran hostage crisis occurred. Eager to have the conflict relieved, the Shah left the States after receiving medical attention, spent a brief time in Panama, and wound up in Egypt, where he died on July 27, 1980. Pahlavi University became Shiraz University. Power in Iran had changed hands, and the Iran hostage crisis continued.

The crisis provoked discussions at the Penn campus. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s action upset a lot of the Iranian student population. In November 1979, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) forced the Iranian students across the country to report to officials. If they did not, they faced a possibility of deportation. Penn complied and set up interviews for the 115 Iranian students on campus at the time. It wasn’t just the United States government that was concerned about Iranian students’ reactions to the news from home – it was also individuals. Although some student groups, like the Black Student League gave official support to the Iranian student population, others individuals made statements like “Send back the Iranians” and even “Nuke Iran.”

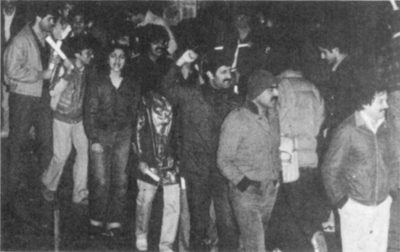

The two Iranian student groups, the Iranian Students Association (ISA) and the Confederation of Iranian Students (CIS), though both had officially opposed the Shah, opposed each other. This was evident on the night of March 31, 1980, when the ISA protested against the CIS (pictured at right) as they celebrated the Iranian New Year. Despite the fact that Ali Tousi, the organizer of that night’s CIS festivities, stated that the CIS supported the Khomeini government, the ISA claimed that some members of the CIS were agents of the Iranian secret police and that the CIS were funded by both the CIA and the Iranian Embassy in Washington, D.C.

On April 25 of that same year, a fellow at the Penn Middle East Center, Dr. Christos Ioannides spoke for two hours with “Mary”, revealing that the Iranian militants believed that they would triumph, the Shah would stand trial, and Western imperialism would fall. “Mary” (shown in a picture to the left during one of her news reports), was a student militant in Iran and the spokesperson for the news-media during the entire course of the Iran hostage situation. Ironically, her father, who taught at Tehran University, had received his doctorate from Penn. Niloofar Ebtekar, Mary’s real name, had lived for three years in the Philadelphia suburb of Upper Darby. Not soon after that interview, though, the United States failed at an attempt for military retrieval of the hostages, another action contended by intellectuals on the Penn campus. The resolution of the hostage crisis was hastened by Iraq’s invasion of Iran in the fall of 1980, leading to the release of hostages after 444 days, on January 20, 1981, soon after President Reagan was sworn into office. Nevertheless, subsequent problems in Iran aroused emotions in the Iranian student population, and they continued to protest on the Penn campus.Another Instance of Penn Involvement in the Middle East

In 1979, the University trained ten junior diplomats from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in a year-long program, which caused some controversy, mostly over the issue of the program possibly politicizing the University. There was a concern that the program was being used as a front for Penn to engage in the international arena. Some were upset with any relations with the United Arab Emirates, a country known for discriminatory policies against women and Jews. Nevertheless, the program continued under the leadership of Frederick Frey and Thomas Naff (pictured at right). Frey was Chairman of the Graduate Group on International Relations and Naff was the Director of the Middle East Center and a professor of Middle East history.Penn and Afghanistan

In the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on December 24, 1979, various efforts were organized on campus. The Muslim Students’ Association at Penn participated in the nationwide “Afghan Relief Fund” in which donations were airlifted to refugee camps in neighboring Pakistan. Provost Vartan Gregorian expressed hope for the situation when speaking to Penn alumni at the University Museum and the City of Philadelphia made Friday, August 15, 1980 “Solidarity Day” with the Afghan refugees. The Afghan Relief Committee urged Philadelphians to join the effort to aid the refugees. The proclamation, received by Jamal Mimouni, chairman of the local committee which was based at Penn (Mimouni was a graduate student), received the proclamation of “Solidarity Day” from the Deputy Mayor of Philadelphia, Evelyn J. White on August 13, 1980. Two weeks later, a news conference was held at Penn to discuss the situation in Afghanistan. Some of the speakers included a former professor from Kabul University and a professor from Villanova University who was a former official in the Afghan government.