The University of Pennsylvania surely had relations with the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union before World War II, but there are scant records relaying what occurred between this institution and that country for that period, so the story of Penn’s global engagement with this great nation picks up five years after the death of Stalin, in 1958, a couple of years after the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

1950s

In February of 1958, Russian scientists visited the University of Pennsylvania. This is an early example in the Penn records on relations with Russia that show a visit of faculty in this field. The trend of scientists from Russia visiting Penn continued throughout the second half of the twentieth century. It seems that there should be no doubt that this trend grew much in the 1960s due to Khrushchev being the leader of the Soviet Union at the time, with his cooling-down of relations between the two super-powers. The picture above shows President Gaylord P. Harnwell meeting with three Russian scientists and the leaders of the laboratories of Smith, Kline and French, which worked in cooperation with the University of Pennsylvania at the time. One month later, in March, Andrei M. Ledovski, the counselor of the Soviet Embassy in Washington, spoke in Dietrich Hall on the subject of Russian education. Ledovski declared that “[i]f the climate of the Cold War isn’t a few degrees warmer – in the friendly sense – today, it is through no fault of some University of Pennsylvania students and a good-natured Russian diplomat.” The belief was declared, sometime during his speech, that the two superpowers could live in harmony with each other. In May, Dr. Harnwell made a visit to the Soviet Union with six other college and university presidents, to examine Soviet universities. Edward H. Litchfield, the chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh lead the trip, and that University, under the joint report of the seven-member delegation published a report that same year on the Soviet university system.

In June, 1958, cooperative research that was done in the field of Arctic Anthropology revealed that an ancient people of Alaska were not ancestors of Eskimos, but rather Siberians. At a conference two years prior in 1956 at the University of Pennsylvania, a Committee had met to set up scientific information and cooperative research by the International Anthropological and Ethnological Congress. Representatives in the field from the US, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Norway and the Soviet Union had met at a conference in Copenhagen in May 1958, and Dr. Froelich G. Rainey, the Director of the Penn Museum, revealed that a Russian anthropologist had spent two months in the Penn museum and in the Museum of Natural History in New York examining a collection of ancient skeletons. They had been discovered by an expedition to Point Hope, Alaska, which Rainey had headed from 1939-1941. International collaborative scientific research was familiar to Penn, and it continued many years with the USSR before that nation began its gradual collapse.

1960s

In February 1960, a delegation of twelve Russian government leaders toured the University of Pennsylvania campus and met with student representatives. The tour itinerary, written in Russian for the benefit of the leaders, is preserved in the University Archives (Appen.). Later that year, though, an extremely important event occurred. In August, the first Russian student since World War II was enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania: Valerii Aleksandrovich Postnov. He was to attend the Towne School of Civil and Mechanical Engineering in the summer. Postnov came to study and research under the auspices of the Inter-University Committee on Travel Grants (then headquartered at Indiana University). The committee had been formed to help furnish exchange between American universities and institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Postnov was sent by the Minister of Higher and Specialized Secondary Education of the USSR.

Two Soviet metallurgists visited the University of Pennsylvania campus in February 1962. Dr. G. V. Kurdjumov hailed as the chief academician of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and Dr. Leo M. Utevsky. Dr. Kurdjumov discussed “The Effect of Irradiation on Cold Worked Metals” in the Physical Sciences Building as a seminar open to the public, which was sponsored by the School of Metallurgical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. Several years later, in 1967, Igor Bubnov, First Secretary of the USSR Embassy in Washington and a number of American specialists (acting as panelists to speak) on Russia met at the National Conference on the Soviet Union, held in April at the University of Pennsylvania. Later that same year, in July, an open forum was held in Houston Hall by two Soviet diplomats (A. Bogachov, First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Washington and V. Zaitsev, circulation editor of “Soviet Life”) and two University scholars (Professors Alfred J. Rieber and Wolfgang Klaiber). This forum was held to discuss “Changes in Soviet Life.”

1970s

The 1970s would mark a change in Penn relations with the Soviet Union. The latter half of the 1960s showed more concentration on the Penn side to examine the culture and history of the Soviet Union. This trend would continue into the next decade. In 1972, President Richard Nixon took a trip to the USSR. Because of that event, the University of Pennsylvania sent a list of Russian history scholars to the government, in the event that Washington would need aid in preparations. Three members of the Penn faculty appeared on the list: Dr. Alvin Z. Rubinstein, Dr. Alexander V. Riasanovsky and Dr. Alfred J. Rieber. A notice of a campus event titled “Scriabin Happening” appeared in April 1975, as Edith Finton Rieber on April 16 performed selected piano works of Alexander Scriabin with a light show (rarely performed), which conceivably entertained more interest in Russian culture. In 1977 there was a conference held at Penn on Soviet-European Relations sponsored by the Anspach Institute for Diplomacy and Foreign Affairs and in 1979, public lectures were held on Russian science and culture in the University Museum, a program was held titled “Inside the Soviet Union” and three archaeologists from the Academy of Science in Moscow visited Penn. In the early 1980s, though, as the collapse of the Soviet Union drew near, relations between Penn and the USSR faltered as Soviet policy upset academia in the West.1980s

A sure mark of problems accelerating occurred in 1979, when the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Afghanistan. In April 1980, Muslim students at the University of Pennsylvania organized a relief fund to aid those refugees fleeing Afghanistan in the wake of the Soviet attack. Money and clothing, donated by the community of the University of Pennsylvania, was integrated into a nation-wide campaign and the items were to be airlifted to Pakistan for the refugee camps. But the Soviet invasion was not the only outcry against the Soviet Union in the 1980s seen on the Penn campus. In April 1980, the Penn Physics department joined an international appeal on behalf of Naum Meiman, a Russian physicist. Although the Soviets argued that Meiman’s release from an isolation enforced upon him (which began in 1975) was a national security issue, many people in the West including Penn community saw the problem for what it was. The Soviets focused on halting the progress of their Jewry, of whom many had been applying for exit visas to Israel. Meiman was one of them. In protest, Professor Sidney Bludman held a “Seminar-in-Exile” in his apartment in March 1981, protesting through mockery the isolation of Soviet scientists who had become dissidents, better known as “refuseniks” or those who had applied for exit visas and had been denied by the Soviet government.

Regardless, the Soviet policy against the Jews continued and was apparent to Penn when the story of Anatoly Shcharansky was revealed through a rally on the College Hall Green by the Philadelphia Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. Shcharansky had been exiled to a Soviet labor camp, become nearly blind and was ailing, and was reported close to death. The Soviet government was to return him to solitary confinement and Susan Friedman (SSSJ Chairman) stated that he would probably die from such treatment. Friedman urged the crowd at the Van Pelt Library to protest. One hundred signatures were collected for a petition to Brezhnev to free Shcharansky. Fortunately the story ends well: Shcharansky was released in late 1985 under the new Soviet President Gorbachev and went on to become the Israeli ambassador to the United Nations in 1997.

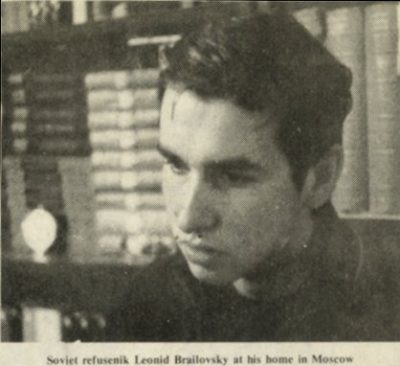

Perhaps the most apparent campus protest of Soviet policy against the Jews, though, occurred the next year, in 1982 when “A Letter from Leonid” appeared in the April 23rd issue of the Daily Pennsylvanian. The text read as follows:Dear Friends,

My family applied for exit visa in September, 1972 when I was 11. I began to feel what is to be in refusal when the teachers of my math school heard of application in 1976 and I was expelled. I got the secondary school diploma from the school of adults. I’m interested in mathematics but had no possibility to enter the University, being a Jew.

When I become 18 and was allowed to apply for visa alone I immediately used this opportunity, but got the refusal under the pretext that Soviet officials don’t want to split my family. I try to study math myself and keep trying to get out of the country. The only thing that keeps me relatively safe here and the only thing which may help me to get my visa is the help from your side. Besides, being in a way excluded from Soviet society it’s awfully important to feel your sympathy and support. I’m very grateful to you for your efforts and I still hope that I’ll have the chance to see your university and speak to you directly.

Yours,

Leonid

Leonid Brailovsky had been accepted to the University of Pennsylvania as a member of the class of 1985. However, the Soviet government refused him an exit visa, and he was unable to attend. Brailovsky’s picture can be seen above (the photo was taken in January 1983 when Penn students visited him in Moscow on a trip to the Soviet Union). In that same issue of the Daily Pennsylvanian, it was revealed that more than sixty-five members of the US Congress had signed a letter to Anatoly Dobrynin (then the Soviet Ambassador) on behalf of Brailovsky. Nonetheless, Brailovsky was not granted an exit visa. On September 20th, President Sheldon Hackney stated that the University had continued to protest for Brailovsky. Hackney received a citation from William Green (former Mayor of Philadelphia) for his efforts, and on the date of that ceremony, Locust Walk was renamed “Brailovsky Way.” The ceremony date was also Brailovsky’s 21st birthday.

The campus continued to protest throughout the rest of 1982 and 1983. A 5-kilometer run was organized in which members of the University community, including faculty, ran in protest of the Soviet government. The picture of the event, shown to the left, was taken by Mark Pochapin of the Daily Pennsylvanian. In February 1983, Penn students joined students across the nation to rally in Washington D.C. Although the protest outside of the Soviet Embassy was officially canceled due to the weather, students nevertheless gathered there; the picture below shows the protesting University students. Later in the day, twenty-five students from Penn met with Shep Donager (an aid to Senator John Heinz, then the US Ambassador to the Soviet Union) to explain the Brailovsky situation and the bigger picture. As they told him, only two thousand Jews had been permitted to leave the USSR in 1982. In 1979, the number allowed had been 51,000.

Although two positive examples of engagement between Penn and the USSR did occur (the Wharton School graduate, Mike Storm, accepted an offer from the Soviets to be trained there for the 1984 Olympics and a non-credit Soviet film series was mildly successful), the issue of Soviet policy against the Jews could not be overshadowed.

The section on study abroad will provide background on Penn-Soviet student exchanges in later decades, during the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the Russian Federation. It is only pertinent to mention that the Soviet Union would collapse less than a decade after the Brailovsky protest, and relations between Penn and that country would gradually be repaired.