The first Japanese student to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania appears to have been Tosui Imadate, who graduated with a Bachelor of Science in 1879. The first Japanese student to have graduated from the Medical School seems to be Osam Nagura, who graduated with a Medical Degree in 1880. The Japanese alumni from Penn seem to have been quite active in the first half of the twentieth century: for example, Sadijiro Suguira established “The Same Window Society,” the first Penn alumni association, in Japan in 1903. Also, the Japan Students’ Club was active as early as 1928. But it is easier to mark trends and patterns in Penn’s relations with Japan during and after World War II.

In 1942, Sannosuke Yamamoto, a Japanese man whose daughter attended the Penn campus, began to teach the language of Nippon to men in the military at the University of Pennsylvania (pictured below). Of course, it must be understood that Yamamoto had been in the United States since 1905.

*Anti-Japanese sentiment was perilous to people of Japanese descent in America after Pearl Harbor. In mid-1942, 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast were rounded up and confined in government camps. While Philadelphia was far from the Pacific Coast, the Penn campus was not unaffected. The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania made a clandestine policy following the outbreak of war not to accept any new students of Japanese ancestry for the duration of the war. The handful of Japanese American students who were already students at the University would be permitted to continue their studies and obtain their degrees, but not to go beyond the program they were already enrolled in (for example, an undergraduate student could complete his Bachelor’s degree, but would not be accepted into graduate school). As a result, two Japanese American students from Hawaii, Koshi Miyasaki and Robert Yoichi Sato, were denied admission for further studies after completing their degrees. Another student at Penn wishing to pursue graduate study who was affected by the policy at this time was Naomi Nakano (pictured below). Born in Philadelphia, the daughter of Yosuke “Nick” Nakano, a Japanese immigrant who was a Penn alumnus, Nakano was an honors student and President of her junior class at the College for Women. However, she was denied admission to the graduate school as a result of her Japanese descent. While Nakano enrolled at Bryn Mawr for graduate studies, a group of her friends, led by Carolyn Merion, were outraged by such an apparent case of racial discrimination. Merion and Dr. George H. Menke, the Regional Secretary of the Student Christian Movement, attempted in vain to obtain an official explanation for the exclusion. Penn administrators refused to comment beyond vague statements that the policy was adopted “at the suggestion of the Navy.” However, when newspaper reporters interviewed the head of the local Navy security program, Bureau of Personnel Chief Admiral Randall Jacobs, he remarked that he had never heard of such a[n exclusionary] rule it sounds cockeyed to me.” In the end, the University withdrew its opposition and admitted Nakano, but by that time Penn’s exclusionary policy had attracted nationwide condemnation.*

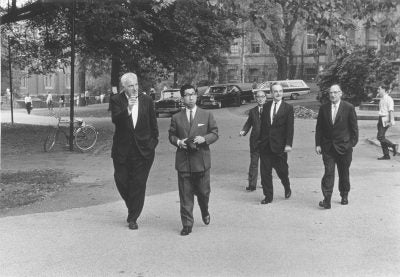

In 1965, the University of Pennsylvania was visited by members of the Japanese royal family. Prince Mikasa, Princess Mikasa and their daughter, the Princess, attended a luncheon and toured the campus. Prince Mikasa was the youngest brother of Emperor Hirohito. The royal entourage, composed of ten individuals, were greeted by Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell. The Prince (pictured below with Harnwell), who was a student of Near East history went to see that collection at the University Museum and spoke with other Japanese countrymen in the Oriental studies section in the library. In 1968, the Department of Oriental Studies was aided in its East Asia Division by the efforts of Dr. Saburo Kitamura in Japan, who had graduated in the College class of 1930 and the Medical School in 1936. Kitamura helped develop a book fund whereby the University Library would receive more texts in Japanese. He explained that the year was a good one to develop such a program as it was the 100th anniversary celebrating the Meiji Emperor opening Japan’s doors to the West. As Western knowledge had poured in one hundred years prior to Japan, it was only right that Japanese knowledge would flow into America as well. That knowledge flowed into the University of Pennsylvania. At the time, Penn offered courses in Japanese “medieval prose and drama… [as well as] the linguistic approach to the study of [Japanese] history and structure of the [Japanese] language.” It was one of the only institutions to do so. The book fund would aid this work as well.

Kitamura’s story is an interesting one in and of itself. After graduating from Penn, he went home in 1940, only intending to be there for a short visit. It would last twenty-five years. After having worked in a Tokyo hospital in 1942 as the only doctor on site, he was found after the war by Penn professor Eugene P. Pendergrass. Through Pendergrass’ efforts, Kitamura (pictured below) became the head of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, an organization designed for the treatment of victims of the Atomic bomb. After spending some time in Hiroshima, he returned to Tokyo where he opened the Kitamura Diagnostic Clinic.

The Wharton School and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, in early 1980, held a symposium on the Japanese economy, Japanese history and Japanese sociology. There, the former United States Ambassador to Japan, James Hodgson, stated that “The American-Japanese bond has become the singlemost relation. They have the two great economies in the world. Each nation, however, needs a better understanding of the other in the years ahead.” The envoy to the Japanese mission to the United Nations, later stated that, “[t]hrough these seminars, the differences between the two nations can be better understood.”

In May 1983, with the aid of two grants, the Institute of Medieval Japanese Studies was enabled to purchase materials that would aid in scholars using the slide and microfilm archives therein. The Institute had been established in 1968, financed by grants from both the University of Pennsylvania and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). As of 1983, it was the only one of its kind outside of Japan. The materials being purchased in the 1980s would also aid in the analysis of reference materials that the Institute had acquired through Dr. Barbara Ruch, while she was in Dublin, Ireland. What she had acquired were the “only such materials in the world.” The grants for the research materials, which included a purchase of a five-hundred volume set of reference works, were donated by the Japan World Exposition Commemorative Fund and the Japan Foundation.

That same spring, a new United States-Japan Center was created at Penn as “the first university-based research operation to develop data on the Japanese economy and its interaction with the U.S. economy.” For eight weeks that summer, a Japanese delegation composed entirely of executives stayed at the Wharton School studying American management techniques. The Center was financed by the efforts of both American and Japanese companies.