The Vietnam War lasted from 1959 to 1975. The United States entered the war in 1964 and peace talks began in 1968, followed by President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization,” with the total withdrawal of United States personnel in 1975, during the fall of Saigon. College campuses are best known for their opposition to the Vietnam War, mostly beginning in 1964. The University of Pennsylvania had a large amount of student activism – as much, if not more, than many of the other college campuses in the United States. This report can not seek to cover all of the opposition that occurred on the Penn campus, and there extensive information on it in the University Archives, but it does seek to give a general overview of it. A more complete story of student activism against the Vietnam War at the University of Pennsylvania would be a worthy subject in itself for another report.

Posters appeared on the Penn campus in April 1965 for students to join the Washington March against the Vietnam War, which would occur on April 17. Only a little more than a week prior, 1,200 people had attended a teach-in in Irvine Auditorium, which featured Representative George Brown (a Democrat from California) “call for American acceptance of “self-determination” by the people of South Vietnam.” From April 8 to April 15, 1967, Vietnam Week was held on campus, with events including teach-ins by members of the Penn faculty, and ended with a mass march and rally at the United Nations. In the Vietnam Week Committee Demonstration in 1968, forty-six faculty members participated including W. Allyn Rickett, mentioned earlier in this report, and Humphrey Tonkin, who would later become the Director of the Office of International Programs in 1977.

In the New York Times, on Sunday, June 5, 1966, a large petition appeared, calling upon the government to halt its current policy in Vietnam and re-evaluate the situation there. The petition was signed by faculties from colleges and universities across the country and professionals in various academic fields. Sixty-seven Penn faculty members’ names appeared on that petition. However, feelings of the Penn faculty at this point were mixed – in a poll from the Almanac in February 1966 of one hundred and thirty two faculty members, twenty-eight members agreed with U.S. policies, thirty-four disagreed, and besides seven others who gave qualified answers, sixty-four of the faculty polled had no response. Students, though protesting en masse throughout the war years, in 1967, according to a referendum by the Student Government had mixed feelings on the war as well.

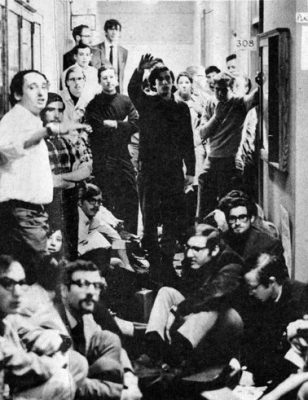

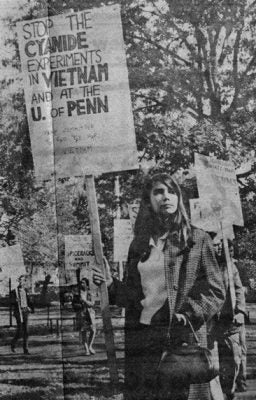

One reason for protest was Penn’s involvement with the Dow Chemical Company. In early November 1967, at a recruitment effort by Dow Chemical Company and the Central Intelligence Agency, Logan Hall was filled with approximately eighty protesters lining the hallways in a large sit-in (a type of event to occur frequently at college campuses in the years of the Vietnam conflict) to disrupt recruitment efforts (pictured at left). The Dow Chemical Company was the principal supplier of napalm to the Department of Defense. The acting Dean of Men, Gerald Robinson, did what he could to calm the situation. It was to no avail – Robinson apparently had to ask the Dow recruiter to leave and the CIA recruiter, eventually having the office he was using flooded by students, left in a hurry, flanked by campus security. Robinson had earlier “told the demonstrators that they would be removed by campus guards if they attempted to block doorways… his threat was not carried out [because] it would be ‘an inappropriate function for guards to carry them out.’… also… the guards were not capable of doing it.” In the same week, it was decided that an open discussion on the University and its connection to the Vietnam War would be held in Irvine Auditorium. That month, some students had also demanded that the University withdraw Navy and Marine information officers from the campus.Another question for protest was the issue of Penn’s “bacteriological warfare unit.” In a letter between campus officials, the concern was raised that “civil disobedience” would break out at demonstrations on Friday, October 15, 1965, which would “include throwing themselves [the demonstrators] on the stairs of “the University’s hidden, top-secret bacteriological warfare unit.” It was also suspected in that year that the campus Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had been infiltrated by communists at the national level. The SDS and the Philadelphia Area Committee protested outside the Institute for Cooperative Research (ICR) did protest at Penn that month. It was the ICR that was the alleged “bacteriological warfare unit.” While the campus did admit that it researched biological and chemical warfare, it was stated that it was being done from “a defensive standpoint.” In October 1966, the University Committee to End the War in Vietnam (UPCEWV) held their second rally at Houston Hall (pictured at right). One of the items they protested was the ICR, though at that time, the University reported that the ICR had been disbanded, even if in January 1966, Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell had stated that the work of the ICR had no direct relation with warfare in Vietnam.

However, as of 1969, the official attitude of the campus did not really move against United States involvement in Vietnam as a group. The Trustees did not wish to engage the University in questions of national policy. Here again appears the issue of institutional morality that would plague the University in its relations with Iran in the 1970s and South Africa in the 1980s, mentioned earlier in this report. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences decided “not to consider a resolution which, if passed, would have committed the faculty to condemn[ ] military involvement in Vietnam. The University Senate stated that, “It is inadvisable for the University Senate to act upon a resolution concerning United States involvement in Vietnam, and the University Senate therefore declines to consider the merits of such a resolution.” Finally, President Harnwell, issuing a statement while flying the United States flag at half-mast, said,

…Individual freedom of expression is fostered at the University of Pennsylvania, but acts disruptive of the University’s purpose, or those which would by inference be misunderstood as abrogating individual freedom of expression through committing all members of the University to a common institutional position, are not condoned.

No doubt, this was said in response to a student attempt to stop the flag from being raised on the morning of October 27, 1969. A fifty-year old faculty member, Dr. Robert E. Davies, took it upon himself to scale the flagpole (with his mountain-climbing gear) which had been greased and from which the ropes had been cut. Davies succeeded and the flag flew in the morning. Davies stated quite clearly that his efforts were only to “avoid ‘bad publicity’ for the University.” Not entering into discussions of institutional morality was and always will be a question for college campuses, and will probably increase as globalization continues.

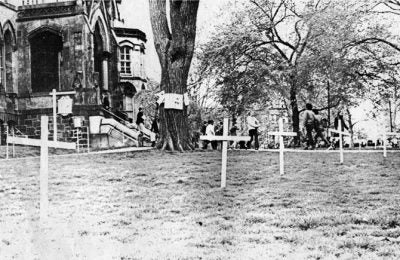

This attitude of not entering into questions of institutional morality, though, was only prevalent in official campus policy. Other organizations did protest the War in Vietnam. A joint editorial in 1969 was printed by the eight Ivy League university and college student newspapers calling for the immediate withdrawal of troops from Vietnam. In the School of Social Work, the Graduate Students Association “call[ed] for the immediate withdrawal of all American forces from [Vietnam] and [d]emand[ed] a reversal of national priorities away from militarism in all of its guises and toward social reform in this nation.” An “ad hoc committee” of students and faculty held a “Vietnam Commencement” in 1969 to commemorate those 1969 graduates who were expected to perish in the Vietnam War. Another one of these ceremonies was held in 1970 (pictured below). The official campus line, though, did sanction individuals protesting United States involvement there. For example, Penn President Harnwell would appeal as an individual to Nixon to step-up the timetable for withdrawal from Vietnam along with seventy-eight other college heads, who appealed as individuals, themselves.

However, in times of war, though people may be opposed to a government’s policy, many do not find problem with supporting the soldiers left to do the duty the government asks of them. Sympathizing with the common American soldier in Vietnam came easily to the Penn campus. In 1965, in a “Mail Call Vietnam” program, headed by sophomore James J. Restivo and junior David B. DuPont, purchased at least 20,000 greeting cards to be sent to soldiers in Vietnam. Many student organizations joined in this project.

October 15, 1969, was Vietnam Moratorium Day, and Penn University students joined with students from across the country for two days to protest in Washington, D.C. The first half of the 1970s was permeated with questions about what was happening in Vietnam and when the United States would completely withdraw. The opposition to United States involvement in Vietnam continued at college campuses. For example, at Hey Day in 1972, some students followed campus tradition while others carried on antiwar protest. In fact, the University of Pennsylvania Marching Band, while moving through the campus during Hey Day festivities was followed by protesters demonstrating against the war (pictured below).

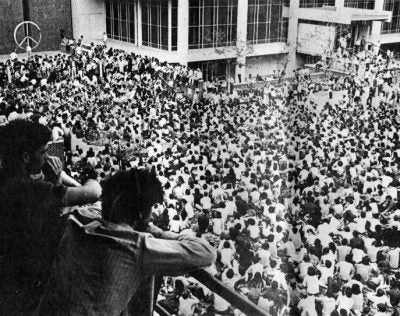

When United States President Nixon announced American military involvement in Cambodia, faculty and students were once again shocked. On the College Hall green, more than 2,500 students gathered to protest (pictured below), and the Deans of fifteen medical schools, including Dean Alfred Gellhorn at Penn, “implore[d] [Nixon] to take unequivocal actions to demonstrate [his] determination to end the war quickly without extension of misery to military and civilian populations.” Protests also erupted with South Vietnam’s movement into Laos. Throughout the early 1970s, the protests continued, at least until the fall of Saigon in 1975.