The involvement of alumni in the restructured Athletic Association soon brought very tangible results. This group urged the trustees to provide students with the University’s first athletic field, resulting in the May 11, 1885 opening of Penn’s Athletic Grounds at 37th and Spruce Streets, the later site of the Quadrangle dormitories. The creation of this field provided a big lift to all Penn sports, including baseball. It was also an important first step towards University influence on Penn athletics. The opening of a newer athletic facility, Franklin Field, in 1894 would further enhance Penn’s intercollegiate prominence in athletics; the building of Franklin Field was also a visible symbol of the new significance of University trustees and faculty in the shaping of sports at Penn. These trends are illustrated in the development of Penn baseball during the 1890s.

Class Teams Continue

During the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century, class teams would continue to play not just each other, but also teams from other institutions. For example, upon its graduation, the Class of 1893 made a great deal of the fact that their class team had won all the championship during all four of its College years. Five years later, the 1898 Record stated that, as freshmen, the Class of 1898 had played Penn Charter and Haverford Grammar School teams as practice for the class games. The classes continued to compete for a trophy.Growing Success and Popularity of Varsity Teams

Gradually, the Penn nine began playing more games and improving their record as each season passed. The varsity’s first winning seasons were 1886 and 1887. Two dismal losing seasons followed in 1888 and 1889. The May 15, 1889 issue of the Red and Blue contained an article encouraging Penn students to come out and support their baseball team by buying tickets and attending games: “Team can’t be encouraged by only 10 or 15 students as an audience. And if the manager gathers only $8 to $15 in gate receipts, but has to guarantee $35 or $40, there is a problem. Complimentary tickets are available for ladies, so bring them out and cheer on your team.”

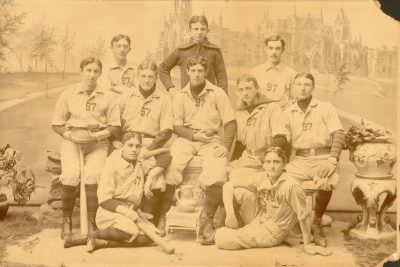

A turn of fortune was on the way, however. The standout season of 1890 marked the beginning of baseball prominence at the University. The team had one of their best seasons ever in the spring of 1890 when they won twenty-one games while only losing three. The 1890 team’s outstanding performance on the diamond seemed even more remarkable in contrast to the dismal record of the 1889 team.

From 1890 to 1904, every baseball season was a winning one for Penn. The period up until 1896 was particularly successful and exciting. By 1893, even before Franklin Field was completed, attendance at baseball games often reached two thousand, sometimes even five thousand; newspapers listed socially prominent men and women sitting in the stands. Not surprisingly, these were the years when varsity players were most likely to go on to play professional ball.

Growing Regulation of Player Eligibility

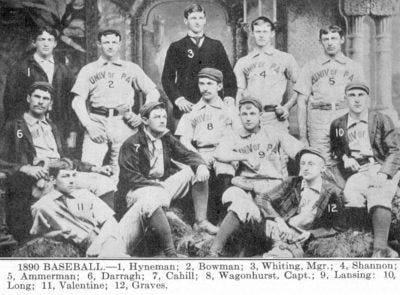

Varsity teams increasingly drew their members from Penn’s growing professional schools. From 1887 through 1898, more than half of each season’s varsity team was drawn not from the College, but from Penn’s Medical, Law, Dental and Veterinary Schools. Although professional school students no longer made up a majority of the teams in 1899 and 1900, players from the Medical, Law and Dental Schools were still included. This professional school presence was a conscious decision by Penn’s players, alumni and faculty to go against the Pennsylvania Athletic Association‘s 1893 limitation of player eligibility to undergraduate students.

The Penn faculty took the lead in providing Penn with alternate reforms. The committee led by Simon N. Patten and George Wharton Pepper issued new eligibility rules in December of 1893 which lay the groundwork for the make-up of Penn varsity baseball teams to follow. These rules addressed issues that faced all American college athletic teams as intercollegiate athletics came of age in the late nineteenth century. Issues such as the use of professional baseball players and the academic performance of student athletes had to be faced and dealt with.

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, as both professional and intercollegiate baseball were taking shape, the presence of professional ball players on college teams was still a gray area increasingly open to criticism. The University of Pennsylvania regulations enacted in 1894 included a clause excluding athletes who had earned money playing professionally from participating in University teams. Interestingly, Penn’s decision to exclude professional players came at the same time many at Penn were pushing for Penn’s entry into an athletic association with Yale, Harvard and Princeton. As one student wrote in the May 1892 issue of the Red and Blue:

Our base-ball nine is conceded to be [one] of the strongest, if not the strongest of college teams on the field. There seems to be no reason why we should not apply for admission to the Inter-collegiate League at present composed of Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. We can see no valid reason on which our admission could be refused. The nine is strictly an amateur one, and has clearly shown by its record that to travel in such company would not be too fast.

This exclusion of professional athletes applied to only three nineteenth century baseball players who played on the 1890, 1891 and 1893 (but not the 1892) varsity teams: Wagenhurst, McGrillis and Bowman. A total of seventeen men who played baseball professionally attended Penn from 1880 to 1900; the timing of their professional playing and any involvement on a Penn team falls into the following categories:

- Two men had played professional baseball before joining Penn’s varsity team: Wagenhurst (1890 and 1891 teams), and McGrillis (1893 team)

- One man played professional ball while a member of Penn’s varsity team: Bowman (1890-1891 teams)

- Six students were varsity baseball players at Penn before playing professional baseball: Cahill (1889-1891 teams), Darragh (1890-1891 teams), Coogan and Thomas (1892-1895 teams), Boswell (1893-1894 teams), and Goeckel (1893-1895 teams)

- The other eight men, all students in Penn’s professional schools, are not documented as playing varsity baseball while they were at Penn:

- Jesse Allen, Gunning, Thompson, and Sexton played professional ball before coming to Penn.

- Cyrus (Jack) Allen, Bushong, and Smith played professional ball while a Penn student.

- Hayden played professional ball in 1901 after leaving Penn

By the mid 1890s, Penn’s University Committee on Athletics examined each sport’s proposed list of varsity players to decide eligibility. Previous professional experience was one consideration, but other factors also emerged. Penn was part of the wave of reform against “summer baseball” which swept eastern universities. Summer baseball teams, including one in Cape May, had served both to train young athletes and also to allow professional teams a venue for scouting out potential players, but now this kind of play was seen as suspicious, particularly if the young athlete had received monetary payment, room or board, or any other kind of compensation. Penn also instituted prohibitions against athletes playing on both class and varsity teams in one sport and against playing multiple varsity sports. And of course, more attention was now paid to the academic standing of varsity players. For a time there was confusion and uncertainty among student athletes as the new system fell into place. And the new standards led to rejections of some student athletes, but these rejections were offset to a certain extent by the increasing size of Penn’s student body.