Introduction

From Penn’s beginnings in the mid-eighteenth century, students have engaged in athletic activities; the earliest recorded student athletic event occurred in the 1760s, a foot race recorded by student Alexander Graydon in his 1811 memoirs. Impromptu contests and games are inevitable wherever young men gather, and the Academy and College of Philadelphia would have been no exception.

The Trustees and the Provost first became interested in supporting athletic exercises in the spring of 1831, after some complaints that the health of students was being compromised by too much studying. An arrangement was thereby made with Mr. Roper’s gymnasium whereby College and Academy students, for a reduced fee of twenty dollars per annum, were entitled to an hour of gymnastic instruction each day. By the 1850s, many students learned to spar and fence at Tom Barrett’s gymnasium, on the upper floors of a building on Market Street above Eighth Street, around the corner from Penn’s Ninth Street campus.

Organized student sports with teams and scheduled contests, however, emerged later. The first sports organizations made up exclusively of Penn students were the Junior Club, founded in 1842, and the Barge Club, founded in 1854, to organize cricket and rowing respectively. Both of these organizations did not endure as Penn athletic organizations. The Junior Club, although very popular for four years, faded away after 1846; and after a few years, the Barge Club began admitting non-students. New student sports organizations devoted to cricket and baseball appeared in the 1860s; rowing, football, and track and field followed in the 1870s.

As Penn athletics began to take shape in the 1860s and 1870s, sports teams and events were initiated, financed and run by students. By the end of the nineteenth century, responsibility and control would shift from students to the trustees, administration and faculty of the University. Changes and expansion in Penn’s campus, curriculum and student enrollment would be accompanied by changes and expansion in athletics. The University would not only provide facilities and financial support, it would also exercise significant control of student teams.

In the early years of collegiate athletics, the organization of teams on the Penn campuses bore only limited resemblance to its current form. Organized college athletic programs and intercollegiate sports were still in their infancy in this post Civil-War era. Student athletes were not working within the organizational framework we know today. As the last half of the nineteenth century progressed, students progressed from pickup games to class rivalries to intercollegiate competition. First Penn alumni and then Penn trustees and faculty joined with students in the shaping of student athletics into forms familiar to us today.

Changes in Campus, Curriculum, and Student Body

The University underwent monumental changes in its campus, curriculum and student body during the last half of the century, changes which would influence the development of Penn athletics. In 1872 the campus moved from its two buildings on the Ninth Street campus to the expanding campus in West Philadelphia, providing a boost for the existing teams of cricket, crew and baseball and for the emergence of new sports on campus. In 1875, although the new campus still had only two buildings, College Hall and Medical Hall (now Logan Hall), there was enough open space to encourage informal athletics. By 1885, the campus property had expanded and new buildings built, including Hare Laboratory, the nucleus of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, a Biological Hall, and a veterinary facility as well as the University’s first athletic field. More property was acquired and more facilities built during the 1890s, including the Law School, the first women’s residence, Morgan Laboratory, Hayden Hall, the Quadrangle dormitories, the University Museum, and Franklin Field. The University trustees were now investing not only in academic and medical buildings, but also in facilities aimed at improving student life, such as dormitories and athletic facilities.

During the years from 1850 to 1900, the schools of the University expanded beyond the College and the Medical School to include law (1850), engineering (1852), dental medicine (1878), Wharton (1881), veterinary medicine (1884) and architecture (1890). These new professional and undergraduate schools attracted many more students – and athletes.

The size of the student body increased dramatically after the move to West Philadelphia. In 1850, the University graduated only 25 students from the College and 172 students from the Medical Department. By 1875, soon after the move to the new campus, the student body had not increased, but had become more diverse in its studies. In that year 21 students graduated from the College, 102 from the Medical Department, and 14 from the Law Department; five other students earned certificates of proficiency and one graduate student earned an advanced degree. The big change came in the last quarter of the century. By 1900, 2,673 students were enrolled at Penn. That year the University granted diplomas to 79 College seniors, 180 medical students, 145 dental students, 83 law students, 11 veterinary students; 24 master’s degrees and 15 doctorates were also earned this year. At this time, since a college degree was not required for entry into professional schools, most students in medicine, law and the other professions were about the same age or just slightly older than college undergraduates. Thus over time, even as undergraduate enrollment increased, the number of professional students grew even more, making them an attractive source of athletes.

Changing Roles of Students, Alumni, and Trustees and Faculty

During the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century, first the alumni and then the University administration became more involved in student athletics. Students tried to address issues of organization and financing with the formation of Penn’s student Athletic Association in 1873, just a year after Penn’s move to West Philadelphia opened up new possibilities. But as it became increasingly apparent that more financial help was needed, alumni became more and more involved. In its first years, the Athletic Association limited its membership to undergraduates and focused on the promotion of track and field. In 1879, however, alumni were also invited to join the membership, thus opening up a new source of financing and organizational leadership. At the same time the Athletic Association was discussing the possibility of expanding oversight to include baseball, cricket, rowing and other sports. In November of 1882, when the Athletic Association officially reorganized its officers and board of directors, alumni were named to key positions. The involvement of alumni in the restructured Athletic Association soon brought very tangible results.

These alumni, led by John C. Sims, worked with Provost William Pepper and the University trustees to provide the land for an athletic field, the first involvement of the University in student athletics. In May of 1883 the trustees approved the use of the land between 36th and 37th, Pine and Spruce Streets for athletic purposes. The tangible results of the trustees’ commitment came in 1885. First, in January, the Trustees formally instituted a Department of Physical Education, with Professor J. William White, M.D. at its head. Then, on May 11, 1885 came the opening of Penn’s “New” Athletic Grounds, the later site of the Quadrangle dormitories. In December, a gymnasium was opened on the lower floor of College Hall.

The existence of the athletic field provided a big lift to all Penn sports, including baseball, and also initiated a new emphasis on intercollegiate sports at the University. Within a few years student athletes were lobbying for more facilities, leading to an even greater commitment by the University to student athletics. Since the University was beginning to build the Quadrangle dormitories south of Spruce Street, the Trustees, on October 4, 1892, began the process of securing another piece of land so that the Athletic Association could build an athletic field and also a training house:

On motion the question of authorizing applications to the City authorities for the vacation of Woodland Avenue, and of dedicating temporarily to the Athletic Association the plat of ground bounded by 33rd Street, Marston St., the Junction R.R. and South St., was referred with power to the chairmen of the Athletic Association (Mr. Sims) and of the Committees on Law and Ways and Means.

Within a decade, the “New” Athletic Grounds had become the “Old” Athletic Field; it would disappear completely with the completion of the Quadrangle dormitories on the site.

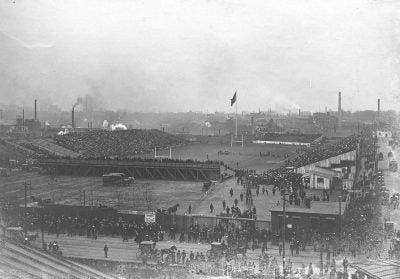

Franklin Field, in its first rendition, was built east of 33rd Street in time for use during the 1894-1895 sports season; its playing field and wooden bleachers were surrounded by a plain wood fence. Permanent Franklin Field construction did not begin until after the turn of the century. Weightman Hall and permanent grand stands were erected from 1903 to 1905. Two years later the J. William White Training House was added alongside the north wing of Weightman Hall. Franklin Field’s grandstands were torn down and rebuilt in 1922, with an upper tier of stands and arcade added in 1925. The Palestra and Hutchinson Gym were the last buildings in this complex, built 1926-1928.

The Athletic Association balance sheet which survives from the year ending June 30th, 1896, provides insight into the financing of Penn varsity athletics at the end of the nineteenth century. Football receipts was the biggest source of income, supporting over half the cost for the entire varsity sports program. The combined receipts for all other sports contributed not even a third of what football brought in. Athletic Association dues, contributions to the building fund, and donations from a variety of individuals and businesses provided the rest of the revenue. Each team had expenses for equipment, uniforms, special meals provided to athletes in training, hotels and transportation. Expenses also included upkeep of Franklin Field and the Training House, pay for managers and coaches, and payments to photographers and printers.

Intercollegiate Athletics and the Regulation of Student Athletes

Intercollegiate athletic events began in the 1860s and 1870s, but did not come to dominate the college sports scene until the late 1880s and early 1890s. Harvard, Princeton and Yale led the way in organizing early intercollegiate sports, but the 1894 completion of Franklin Field, in its first rendition, positioned Penn for a major role in the important intercollegiate athletic world that was emerging. As the 1890s progressed student publications contained more and more articles about intercollegiate athletic events and organizations. Although the National College Athletic Association was not formed in New York City until 1906, Penn alumni and athletes already attended meetings of the influential intercollegiate Athletic Association in New York City. The Penn Athletic Association was also affiliated with the Pennsylvania Intercollegiate Athletic Association which was already in existence. Many at Penn also wanted to join the athletic association formed by Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

These early attempts to standardize intercollegiate athletics were not without conflict, as can be seen in Penn’s actions in the controversy over player eligibility. In 1893 the Pennsylvania Intercollegiate Association passed the Swarthmore amendment which limited intercollegiate athletics to undergraduates only. The University of Pennsylvania, with its many professional schools, was the only institution in the state to object; Penn even withdrew from the state intercollegiate association as a protest to this regulation.As an alternative, Penn advocated following the rules proposed by Harvard. The Harvard proposal limited an individual’s intercollegiate participation to four years for any school, leaving open the participation of students in professional schools as well as those who attended more than one school.

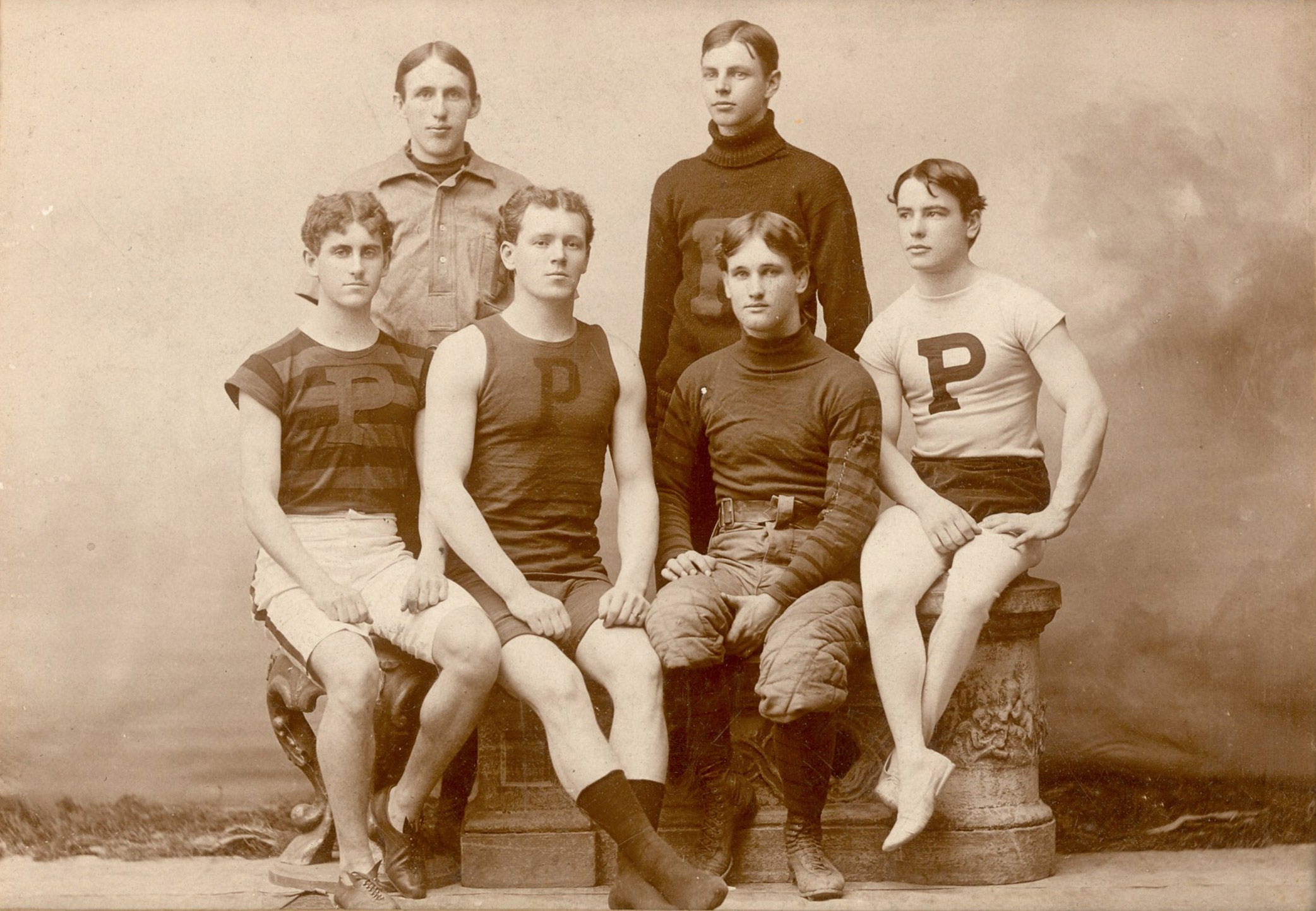

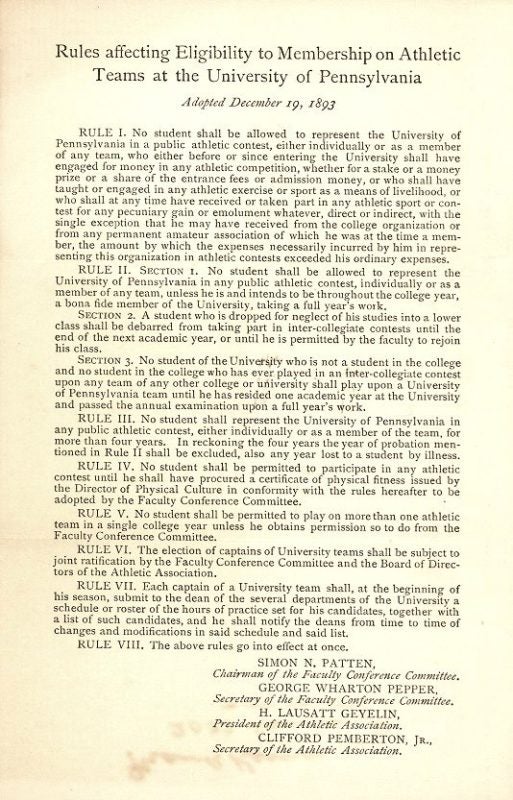

As Franklin Field was being planned and built, the Penn faculty became seriously involved in the regulation of student athletics. In December of 1893 the Faculty conference Committee, led by Simon N. Patten and George Wharton Pepper, issued Rules Affecting Eligibility to Membership on Athletic Teams at the University of Pennsylvania. These rules barred athletes from Penn varsity teams if they had profited financially from playing baseball. Athletes had to be enrolled full-time at Penn, could not play if they had to repeat an academic year, were required to pass a physical exam, and could not play for more than four years; transfer students could not be varsity athletes during their first year at Penn. No student could play on more than one varsity team in any academic year. The choice of team captains now had to be ratified by both the faculty committee and by the Athletic Association, and lists of team members had to be submitted to the deans of the various schools to ensure that players were on sound academic footing.

By the turn of the century, class teams still enjoyed their rivalries in most sports, but intercollegiate varsity teams had come into their own, with regular schedules of contests between Penn and other colleges. Professional coaches and playing facilities were now available, paid for and administered by the University. Both the University and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association were now setting the rules governing player eligibility and other issues formerly in the hands of the students.