George Wharton Pepper, distinguished Philadelphia lawyer and U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania, was born in Philadelphia on March 16, 1867, to George Pepper, a physician, and Hitty Markoe Wharton. His parents were descendants of two old and socially prominent Philadelphia families. Pepper’s birthplace and first residence, 1215 Walnut Street, evidences the extent of his family’s wealth; at the time, an address on Walnut Street was a statement of financial and social success.

Pepper’s father, who graduated from the College of the University of Pennsylvania in 1862, died in 1872, when Pepper was only five years old. Thereafter, his mother assumed responsibility for his early education. From a young age, Pepper’s poor eyesight prevented him from attending school; consequently, he was taught at home, first by his mother and later by a tutor. Home-schooling provided the opportunity for Pepper’s mother, a deeply religious woman, to instill in her son a strong religious conviction. Through her, he became and would remain an active parishioner at St. Mark’s, an Episcopal Church still located in Center City, Philadelphia.

In 1883, with his eyesight vastly improved, Pepper entered the University of Pennsylvania as a member of the Class of 1887. According to the 1887 Record, Pepper was an outstanding undergraduate, not just academically but also in the areas of athletics, drama, publications, and student government. As an athlete, he participated in a wide variety of class sports teams, ranging from crew to football, cricket, and baseball, serving as captain of his class football and cricket teams. At the University level, he was a member of the varsity football and cricket teams and the winner of the half-mile run and the hammer throw on the track and field. He was also involved in a number of social organizations and committees, including the Zeta Psi fraternity, the Sketch Club, and bowl fight committee. A member of the Philomathean Society, Pepper was also editor-in-chief of both the student newspaper, The Pennsylvanian, and a student literary magazine, the University Magazine, before the two merged to become the Daily Pennsylvanian.

Additionally, Pepper played the leading role of Dikaiopolis in the College’s 1886 production of The Acharnians, a Greek play by Aristophanes. Pepper served his class as class president the first term of his freshman year; at the conclusion of his senior year, he was named Spoon Man, the first of four honor awards given during Hey Day to senior men. Pepper received his B.A. in 1887, graduating first in his class.

Following graduation, Pepper immediately entered the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He worked for the prestigious Philadelphia law firm Biddle and Ward while in school and graduated, again first in his class, in 1889. Upon graduation, Pepper received two awards from the Law School: the Sharswood Essay Prize and the P. Pemberton Morris Examination Prize. His prizewinning essay, “The Borderland of Federal and State Decisions,” was cited by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis nearly fifty years later in the landmark Erie Railroad v. Tompkins opinion. Pepper also was selected to deliver the Law School’s commencement address. His topic, “The Rights of Married Women,” proved rather prescient. One year later, on November 25, 1890, Pepper married Charlotte Root Fischer, the daughter of George P. Fischer, a Yale professor and dean of the Yale Theological School. They had three children.

Over the next twenty years, Pepper developed an increasingly successful private law practice while also teaching at the University of Pennsylvania and editing and writing legal reference works. After four years as a teaching fellow at Penn, he became the Algernon Sydney Biddle Professor of Law in 1893, a position that he held until 1910. Following his retirement from teaching, which was a result of his expanding private practice, Pepper became a trustee of the University in 1911.

His work in both the classroom and at the bar concentrated primarily on constitutional and corporate law. At the Law School, he taught classes on the nuances of corporations, partnerships, and insurance. He advocated that law students work by induction from the examination of judicial decisions instead of listening to lectures or studying textbooks. In 1895, at a meeting of the Pennsylvania Bar Association, Pepper presented a paper on legal education and admission to the bar that became a focal point for later reforms.

Pepper’s publications while at Penn were both practical and scholarly. He compiled, in collaboration with William Draper Lewis, the massive Digest of Decisions and Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Law, 1754-1898 (1898-1906). In addition, he authored The Way: A Devotional Book for Boys (1909), A Voice from the Crowd (1915), and Men and Issues (1924). For several years, Pepper also served as the editor of the American Law Register and Review.

Politically, Pepper’s party affiliation changed abruptly in the last years of the nineteenth century. A Democrat prior to 1892, Pepper had voted for Grover Cleveland in 1888. In his mid-twenties, however, Pepper changed his views and became henceforth a loyal and conservative Republican. The same year that he resigned from the faculty of the University, Pepper served as counsel to Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot, who had been dismissed after publicly accusing Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger of mismanaging coal lands in Alaska to assist corporate interests. Pepper’s involvement in a national political event catapulted his political career, making him an even more popular speaker and well-regarded leader on the national level. In 1915, he gave the coveted Lyman Beecher Lecture Series at Yale University; at the time, Pepper was the first layman ever invited to deliver the lectures on religion.

With the outbreak of the war in Europe, Pepper increasingly turned his attention to foreign affairs. He became a leader in the national preparedness movement and served on the Pennsylvania Council of National Defense from 1917 to 1919. He was also a member of the First Provisional Training Regiment at Plattsburg and traveled frequently during the war to rally troops and speak at mass patriotic meetings. Following the war, Pepper was a leading and vocal opponent of President Woodrow Wilson’s Versailles peace treaty, criticizing the settlement’s harsh treatment of defeated nations. He also opposed America’s unconditional entry into the League of Nations, an organization he felt interfered too strongly in the affairs of European nations. Pepper found the use of force to preserve the status quo particularly dangerous and cautioned, in many speeches delivered throughout the Northeast, that the United States should encourage only peaceful settlement of disputes between foreign nations.

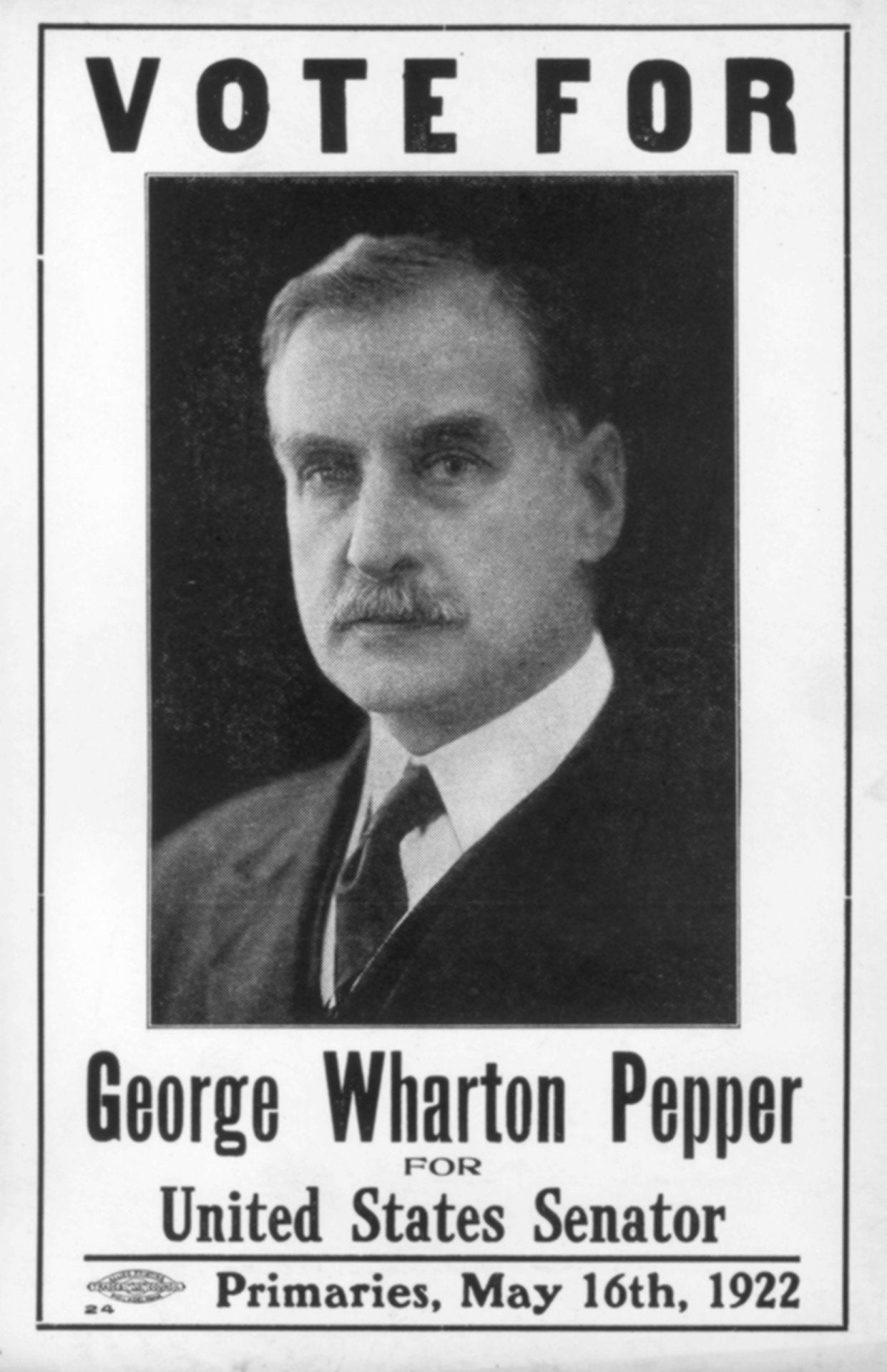

Immediately following the war, Pepper sat on the Pennsylvania Commission on Constitutional Revision. He also assumed a greater role in the national Republican Party; from 1922 to 1928, he served as a Republican national committeeman from his state. After Senator Boies Penrose died on December 31, 1921, Pennsylvania Governor William C. Sproul appointed Pepper to fill the vacancy. Pepper, who had earlier declined to serve as a federal appellate judge and as mayor of Philadelphia, accepted the appointment, persuaded by Sproul’s promise to support him in the 1922 special election for the remaining four years of Penrose’s term. On January 9, 1922, Pepper was sworn in as Pennsylvania’s junior senator. The contrast between the deceased senator and his new replacement was stark; Penrose was one of the last and most powerful of Pennsylvania’s Republican “bosses.” Pepper, on the other hand, was more reform-minded and rejected the influence-peddling methods favored by his predecessor.

During his five years in the Senate, Pepper applied his experience as a corporation lawyer to problems of government and politics. In 1922, only a few months after assuming office, he helped mediate the settlement of the anthracite coal workers’ strike. His success with the strike negotiations boosted his political reputation; in the Pennsylvania primary in May, Pepper easily defeated his Republican challenger and went on to crush his Democratic opponent in November.

While in the Senate, Pepper served on the Military Affairs, Naval Affairs, and Foreign Relations committees. He was also chairman of the committees on Banking and Currency and the Library of Congress. He was actively involved in questions of international affairs, authoring a resolution that would separate U.S. involvement in the World Court from the country’s involvement in the League of Nations. His proposal, however, was later eviscerated by subsequent acts of Congress. In the final year of his term, Pepper was appointed by the U.S. Supreme Court to represent the plaintiffs in Myers v. United States. The case, which concerned the right of the president to remove an executive official without the approval of Congress, further propelled Pepper into the national limelight.

Pepper lost the 1926 Republican senatorial primary, an election he had expected to win. In what turned into an expensive and vicious campaign, Philadelphia “boss” William S. Vare triumphed in a three-way race that also included Governor Gifford Pinchot. Although Pepper carried sixty-two of Pennsylvania’s sixty-eight counties, he could not overcome the political influence of Vare in his home city of Philadelphia. Running on an anti-prohibition platform, Vare successfully clinched the Republican nomination but was immediately criticized for campaign fraud. The U.S. Senate opened an investigation into Vare’s campaign expenses and possible false ballots, and, after Vare’s victory in the general election, continued to look into charges of corruption. In 1929, Vare was barred from taking his Senate seat because of excessive campaign expenditures; the newly-elected Governor John Fisher appointed Joseph Grundy, one of his strongest supporters, to fill the vacancy.

Following his defeat in the Republican primary, Pepper returned to his law practice in Philadelphia. He never again sought public office but continued to be a vocal figure on political issues of the day. In 1936, Pepper, who was an open critic of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, was one of the leading lawyers in United States v. Butler, the Supreme Court case that declared the Agricultural Adjustment Act unconstitutional. He was also a member of the platform committees at the 1940 and 1948 Republican National Conventions.

In addition to his continued political interest, Pepper also resumed his active involvement in the Episcopal Church. Before his time in the Senate, Pepper had been a delegate to many General Conventions of the Protestant Episcopal Church. For the rest of his life, he continued to promote all movements for Christian Unity. He was also an avid supporter of the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. and remained extremely active in Philadelphia’s Protestant churches.

Until his death in 1961, Pepper continued to practice law and to serve professional organizations. He remained for the rest of his life a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania and the Carnegie Foundation. For many years, he was the director of the American Law Institute and for a time its president. He was a former president of the Pennsylvania Bar Association and chancellor of the Philadelphia Bar Association.

In his post-Senate career, Pepper published four books: In the Senate (1930), Family Quarrels (1931), Philadelphia Lawyer (1944), and Analytical Index to the Book of Common Prayer (1948). His autobiography, Philadelphia Lawyer, was hailed by critics as one of the best literary achievements of the year. It serves both as a memoir of his life and as an informal history of United States and Pennsylvania history in the early twentieth century.

Pepper died on May 24, 1961, at the age of 94 at his home, Hill House, in suburban Devon, Pennsylvania. He left a legacy as a distinguished lawyer and politician and one of Philadelphia’s greatest sons.