India gained independence from the British in 1947; at the same time, Pakistan was created by carving out of India its majority Muslim-populated territories. Penn’s relationship with India seems to have come out of or at least gained in impetus by that country’s independence. However, before that occurred, in May 1947, Penn created a summer program of language and area studies of India. That faculty included not only professors from Penn but one from Princeton, another from Hood College and a third who had been with the United States Foreign Economic Administration in India. After that summer, Indian independence was declared on August 15, 1947.

The Carnegie Corporation in November 1947 gave a $155,000 grant to the University of Pennsylvania for purpose to support over five years an Indian and related Asian studies program. The program was interdisciplinary and was especially created to examine this new Union of India and Pakistan, though when the Carnegie Corporation had first seen the proposal, India had still been one unit. It was reported that “the program is believed to be the first comprehensive one dealing with the two nations on a regional basis to be undertaken at an American university.” The special department created to handle the affairs of the program would be headed by Dr. W. Norman Brown (pictured at left), then the Chairman of the Department of Oriental Studies (which he stepped down from) and a professor of Sanskrit. The program was expected to have been completely established at Penn by late 1948. Brown, an authority on Indian studies, had worked for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, conducting research on India. New faculty appointments were created to aid in the undertaking of this program, including those who specialized in not only India, but also Pakistan and Iran.Over the summer of 1955, seven educators Indian educators spent twelve weeks at the Penn campus “studying American methods of vocational education.” Arranged by the United States Foreign Operations Administration, and headed by Dr. Walter B. Jones from the School of Education (he was the Director of Vocational Teacher Education there), they received certificates upon completing the twelve week course (half of which had been various tours) from Penn’s Dean of the School of Education, then Dr. E. Duncan Grizzell.

On December 4, 1955, the chief of the Indian delegation to the United Nations, V. K. Krishna Menon was a guest at a dinner at Bennett Hall. He was invited to campus under the auspices of the Indian Students Association of the University of Pennsylvania. His lecture was entitled “Dynamic Neutralism,” and Menon was at the time an advisor to Prime Minister Nehru. International House arranged the reservations for the dinner and lecture, which was to be attended by the entire Indian delegation to the United Nations. In 1959, the University of Pennsylvania as well as the University of California and the Midwest Inter-Library Center in Chicago began to receive books directly from India as ordered by the Federal Government. In 1951, India had received a Wheat loan from the Federal Government, and to pay for some of the interest, in exchange, the Federal Government accepted government publicans, books, etc. from India, some of which wound up in the Library of Congress and others to the institutions mentioned. Penn Professor of Indian History, Holden Furber, thanked the Federal Government for the materials at an acceptance ceremony attended by L. Quincy Mumford (Librarian of Congress), the head of the Division of Cultural Affairs of the State Department, Robert H. Thayer and others.

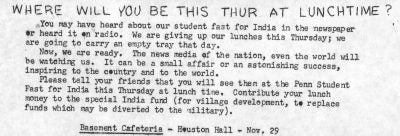

When the Sino-Indian War began in October 1962, the Penn community looked to aid those affected. In November 1962, some Penn students fasted so as to be able to give their donate their lunch money to help Indian victims from the war. The fund, which was created through the efforts of a graduate student, George R. Lakey, stated that “[i]t is well known that we are the wealthiest students in the world. A sheer monetary contribution will not be as meaningful to those who receive or those who give as money obtained through fasting.” Penn students would go through the lunch line at Houston Hall with empty trays, and when they approached the cashier, would give their lunch money to a specific register set-up for the purpose. Whatever was raised would be sent to Acharya Vinoba Bhave, a disciple of Gandhi’s. A flyer was made to draw attention to the event (pictured below).

However, not everyone agreed with getting donations through fasting. Most notable were the Young Republicans who stated,

[w]hile we sympathize with the Indian people in their attempt to throw off the yoke of Chinese Communist aggression, and while we believe it necessary to keep Indian territory out of Communist hands, we object to the attempt to use the recent turn of events to demonstrate that India is now a trusted ally… If anything, India’s recent actions have shown her unworthy to be trusted with uncontrolled assistance.

Earlier in their statement, they had cited Nehru’s endorsement of Krishna Menon’s policies, the same person who had come lectured at Penn seven years prior. Menon policies had apparently failed, as he had been the foreign affairs advisor to Nehru. India had been caught unprepared for war with China. They were also upset about India’s actions in the United Nations and against Indian actions used against the people of Kashmir. The Young Republicans at Penn were very clear in their statements. They wished to aid India if only to halt the Chinese and slow communism.

Regardless, Lakey’s effort was appreciated. A letter arrived from the Indian Ambassador in Washington, B. K. Nehru to Ben Singer in the sociology department at Penn, which stated in part,

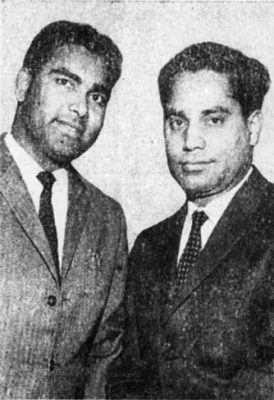

In the end, over two hundred students participated in the fasting. Not long after, the Indian Students’ Association of Philadelphia began an effort in the community to raise funds for the same purpose, and for those families of soldiers who had been killed in the war. Four college presidents, including Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell commended the effort. His name was later attached to a letter from three college presidents to try to convince the public to donate money to the Indian National Defense Fund, in which some students also participated. Two of those students were Kathirisetti Mukundarao and Jaipaul. (pictured to the right).I greatly appreciate and am much impressed with the manner in which your students have decided to show their sympathy with India. Money is important for the defence of freedom; but what is even more important is the spirit of sacrifice and solidarity, both national and international.

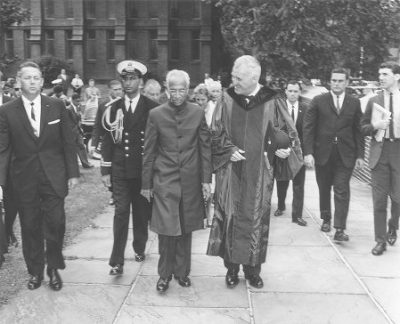

On June 5, 1963, the President of the Republic of India, Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (pictured at the top of this page) received an honorary degree from the University of Pennsylvania from Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell in Irvine Auditorium. On his visit he had also been made an honorary citizen of Philadelphia at City Hall. President Radhakrishnan hailed Philadelphia as “an inspiration to billions of suffering humanity,” when reflecting on the city as the birthplace of democracy and at the convocation at Penn, Harnwell stated that President Radhakrishnan was a “deeply prescient [man] who… lived intimately with people of both India and America and who [knew] legend, fact, poetry and history differentiate between them.” A reception was held after the ceremony at the University Museum, where the Indian President greeted approximately two hundred Indian students.

In October 1965, a program of Indian dance, performed by Balasaravati, who had been touring the United States, was performed at Penn in the Annenberg School of Communications auditorium. Traditional Indian dance would continue to be performed at Penn in the 1970s as well. A course entitled “Theory and Technique of Indian Dance” was taught at Penn in the 1970 fall semester, and the theatre troupe of the Natya Yogam performed in Houston Hall, sponsored by the Department of South Asia Regional Studies and the Graduate Students Association; the Natya Yogam troupe was made of students in the aforementioned course, then being taught by Betty True Jones, an American. That same year, in Irvine Auditorium, the internationally known Kathakali Company, from the Kerala State Academy of the Arts, presented “Ramayana – The Story of Rama” (pictured at left). In the late 1970s, Dr. Kapila Vatsysyan, then a notable member of the Indian Department of Culture, Ministry and Education, gave a lecture on “Indian Dance as a Mode of Communication” in the Fine Arts Building. In 1967, a three-year study was revealed that had been directed by Dr. Philip E. Jacob, who was then a professor of political science at Penn. The study, one of four similar reports, was designed to look at “political leadership at the grassroots level in three Indian states, Maharastra, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh.” The work was financed by the Agency for International Development, and was entitled, “The Interaction of Social Values and Political Responsibility in Developing Countries” (the cover illustration of the report, a woodcut by Gun Kessle of Irajastan wheat harvesters, is shown at right).In 1969, the University of Pennsylvania gained the use of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund to establish an Indian music program. From the Department of South Asia Regional Studies, Dr. Harold Powers would direct the program. From the 1969-1970 academic year, Penn had two Indian artists-in-residence, Sri Jnan Prakash Ghosh and Dr. Lalmani Misra. This new program was designed to be the first phase of the beginning of a South Asian Performing Arts Program at Penn. On October 2, 1969, Powers and the artists-in-residence celebrated the 100th Anniversary of the birth of Mohatma Gandhi with music and prayer (pictured below). In Logan Hall, approximately one hundred Indian and American students gathered for the centennial celebration. Penn was not alone in their commemoration of the birthday – the city of Philadelphia declared “Gandhi Week” that year, which would begin on October 14. Other events for the centennial occurred at the Penn campus, and a handful of students picketed in front of the Hill Residence in protest of the United States Government testing of a nuclear device under Amchitka Island in Alaska. The students stated that they were protesting in connection with the centenary.

One month later, an Indian teaching fellow studying for her doctorate at Penn, V. Ranganayaki, performed at Logan Hall. An Indian songstress, she was accompanied by V. Thyagarajan on violin and T. Ranganathan on mridangam, both who were in the World Music Program at Wesleyan University. Other programs of Indian music were presented at Penn for at least the next five years.

From May 26-May 27, 1977, a symposium was held at the Penn campus about Indian Studies Programs in the United States. This program was sponsored by Penn’s Department of South Asia Regional Studies, as well as the Association of Indians in America. Over thirty scholars and teachers from across the country were to arrive at Penn, and engage in various discussions and seminars. This was followed in 1984, when the Indian Ambassador to the United States, Kayatyani Shankar Bajpai lectured on “India Today and Tomorrow,” which was also sponsored by the Department of South Asia Regional Studies.

![Irajastan [India] wheat harvesters, woodcut by Gun Kessle, 1967](https://archives.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/wheat-harvesters-india-1967-300x400.jpg)