Historical development, 1765-1800

By the end of the eighteenth century, the University of Pennsylvania was made up of the same schools that had existed at the beginning of the American Revolution – the Charity Schools, the Academy (including the English, Mathematical and Latin Schools), and College. The only addition came in 1765 with the founding of the Medical School.

Even before the end of the eighteenth century, the charters for this institution show the evolution of nomenclature and organization of the various schools. In the mid-eighteenth century the institution was known as the “College, Academy, and Charity School of Philadelphia.” When the Medical School was founded in 1765, the College and the Medical School became a university, although the term “university” was not added to the institution’s official title until 1779. The creation of the “University of the State Pennsylvania” in 1779 was accomplished by acts of the new state legislature chartering this new institution and revoking the 1753 and 1755 charters of the College. For the next ten years, the medical school of the University of the State of Pennsylvania operated on the new state charter, while advocates of the College worked to have their 1753 and 1755 charters reinstated. The College charters were reinstated in 1789, and for the next few years both the College and the University of Pennsylvania operated a medical school, resulting is competition and confusion. After Pennsylvania adopted a new state constitution, the “University of Pennsylvania” was created by a 1791 charter as a union of the two rival institutions of the “College, Academy and Charity School of Philadelphia” and the “University of the State of Pennsylvania”. The 1791 charter remains in effect today.

Founding and Early Years

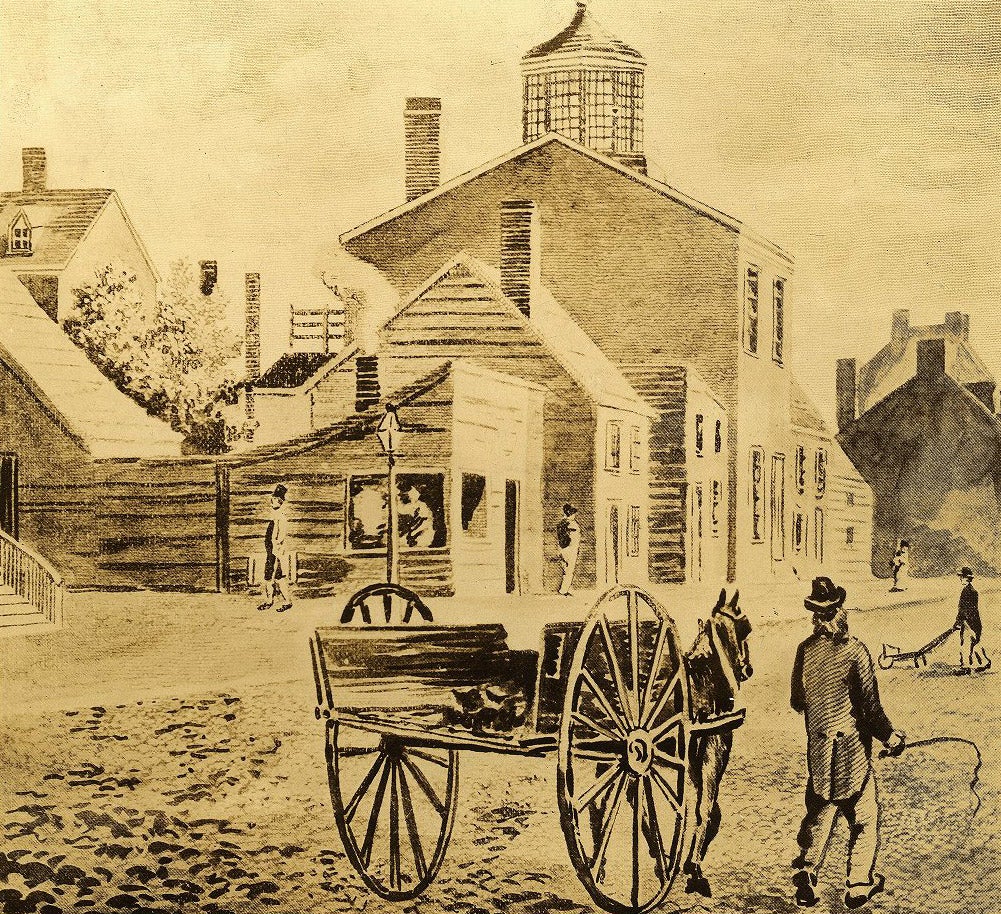

The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine was the first and only medical school in the thirteen American colonies when, in the fall of 1765, students enrolled for “anatomical lectures” and a course on “the theory and practice of physik.” From 1765 through 1801, medical lectures were held in Surgeons’ Hall, on Fifth Street near Walnut Street – not on the Arch Street campus of the Academy, Charity School, and College. By organizing a medical faculty separate and distinct from the collegiate faculty, Penn’s trustees effectively created the first university in North America, though the corporate name continued as the College of Philadelphia until 1779.

The founder of the School of Medicine was a young Philadelphia physician, John Morgan. The early faculty, including Morgan, had earned medical degrees at the University of Edinburgh and supplemented Edinburgh’s courses with further study in London. London offered advanced training in anatomy in private schools owned by men who had become famous in their field. Clinical practice was taught by eminent preceptors in the great city hospitals.

Due to their training abroad, the University’s founding faculty introduced two important elements in American medical education. With the University of Edinburgh as their model, they chose to build their medical school within an institution of higher learning. With the background of their hospital experience in London, they chose to emphasize the need to supplement medical lectures with bedside teaching, which for some time had been provided to apprentice physicians by practitioners at the Pennsylvania Hospital. Founded by Benjamin Franklin, this hospital was located within a few blocks of the College.

Students in the College of Philadelphia’s new Medical School could work for either a bachelor’s degree (M.B.) or a doctor’s degree (M.D.). At the first commencement was June 21, 1768, ten medical students received their M.B. degrees. The College’s first M.D. degrees were granted to four of these men in 1771.

To be accepted into the M.B. course, a young man had to demonstrate knowledge of Latin and the branches of mathematics and natural and experimental philosophy as were relevant to a medical education. To earn a degree, a student had to:

- attend at least one course of lectures in the following subjects: anatomy, materia medica (now known as pharmacology), chemistry, and the theory and practice of physick (the art of healing, or medicine)

- attend one course of clinical lectures

- attend the practice of the Pennsylvania Hospital for one year

- be examined privately by medical trustees and professors and other trustees and professors who wish to attend

- be examined publicly

To be a candidate M.D. degree, a young man must be at least 24 years of age and have earned his M.B. degree at least three years previously. If he then writes and publicly defends a thesis, he will be awarded the M.D. degree.

As for the faculty and curriculum, the first subjects were the theory and practice of physick, taught by John Morgan, and anatomy, surgery and midwifery, taught by William Shippen, Jr. At first Morgan also taught a preparatory course in chemistry, botany and materia medica (pharmacy), but by 1768 these subjects were turned over to Adam Kuhn, who had been engaged as the Medical School’s third professor. In 1769, Benjamin Rush came on board as professor of chemistry, completing the faculty and curriculum offerings for the lecture course required for M.B. students. As for the course of clinical lectures, in 1766 Dr. Thomas Bond began teaching the first such course at Pennsylvania Hospital, and these lectures were included in the early advertisements for Penn’s Medical School.

This medical curriculum was supplemented by a course offered by Provost William Smith; as early as the winter of 1767 Smith offered a course on natural and experimental philosophy in the College which was open to medical students; this course afforded medical students the opportunity to improve their scientific knowledge and to work with the College’s scientific apparatus.

Revolutionary War and the Articles of Confederation

The Revolutionary War curtailed the operations of the Medical School. In October 1775 Dr. Morgan was appointed medical director of the Continental Army; the following summer Dr. Shippen was appointed director of a camp in New Jersey, and in 1777 replaced Morgan as the head of medical affairs in the army – leading to sustained hard feelings between the two men. Dr. Rush was more active in political events, being one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, but he joined the Pennsylvania militia as a surgeon and was wounded at Trenton in 1777. Adam Kuhn, by comparison, had some Tory sympathies, refused to sign the Test Oath of 1777, and after the British withdrew from Philadelphia he left Philadelphia for the West Indies; with the support of prominent citizens and the medical faculty, in 1781 he returned to his teaching and medical practice in Philadelphia.

Lectures for medical students were disrupted more and more as the War progressed; when the British occupied the city in late 1777, all classes stopped and professors attempted to store privately as much as they could of the effects of the College, including the Medical School. In 1779, the newly formed Pennsylvania legislature ended the original College charter (partly because Provost William Smith had Tory sympathies) and enacted a new charter creating the University of the State of Pennsylvania.

The trustees of the University of the State of Pennsylvania moved in the spring of 1780 to get the new medical school established within this new framework by directing that two students in the former medical school be granted their degrees from this new institution that month and also by offering the faculty of the former medical school the same positions in the new medical school. Dr. Shippen accepted at once, Dr. Kuhn was still in exile and Dr. Hutchinson declined completely and Dr. Rush hesitated, being two of those (along with Benjamin Franklin and William Smith) who regarded the disbanding of the original college and the take-over of its property to be unjust and unconstitutional. The faculty of the new medical school took shape very slowly. In the October of 1781, the elderly Dr. Bond agreed to give both the clinical lectures and the lectures on the theory and practice of physick usually taught by Morgan. By the next month, November 1781, Dr. Rush began teaching chemistry and the practice of physick. In the spring of 1782, William Bartram was appointed professor of botany. Finally in 1783, a new election took place, and all of the professors in the original medical school accepted their former positions under the medical school as constituted under the University of the State of Pennsylvania.

1789 Reinstatement of the College

On March 6, 1789, the institutional framework shifted again when the former College succeeded in having declared unconstitutional the act which had, in 1779, terminated its charter in favor of the creation of the University of the State of Pennsylvania.

In the reinstated College, William Smith was restored as provost and the faculty as it existed before 1779 was invited to return. In the medical school of the College, Dr. Shippen returned as professor of anatomy, surgery and midwifery, and Dr. Kuhn was invited to return as professor of botany and materia medica, and Dr. Rush as professor of chemistry. Dr. Morgan, disillusioned by how politics had affected his medical work, had retired, and died in October of 1789, at age 54. Morgan’s death and the existence now of two rival medical schools led to several reshufflings and additions to the respective faculties. At the College’s Medical School, Dr. Shippen was joined by Dr. Rush; new faculty were Caspar Wistar (chemistry and the institutes of physick), Samuel Powel Griffitts (materia medica) and Benjamin Smith Barton (natural history and botany). Dr. Kuhn however chose to be a part of the University of the State of Pennsylvania medical school; he was joined there by James Hutchinson as professor of chemistry and materia medica. The College and the University of the State of Pennsylvania now not only had separate faculties, each also had its own entrance requirement, course offerings and degree requirements.

1791 Charter Creating the University of Pennsylvania

The conflicts and confusion resulting from the existence of the two medical schools was resolved by the act of the Pennsylvania legislature passed on September 30, 1791, uniting the College and the University of the State of Pennsylvania in a new institution, the University of Pennsylvania. When the dust finally settled, the new faculty was comprised of the three surviving professors from Penn’s original Medical School (Shippen, Rush and Kuhn) plus four physicians who had become affiliated with the medical schools as instituted in the 1779 to 1789 period.

The Medical Department (or Medical School) as organized after the 1791 charter consisted of six chairs or professorships.

- Professor of Anatomy, Surgery and Midwifery: William Shippen, Jr. appointed January 23, 1792

Adjunct Professor of Anatomy, Surgery and Midwifery: Caspar Wistar appointed January 23, 1792 - Professor of Materia Medica: Samuel Powel Griffitts appointed January 23, 1792

Materia medica refers to the knowledge of substances used for healing, now known as pharmacology. - Professor of Chemistry: James Hutchinson appointed January 23, 1792

- Professor of Natural History and Botany: Benjamin S. Barton appointed January 23, 1792

- Professor of the Practice of Physic: Adam Kuhn appointed January 23, 1792

Physic refers to the art or profession of healing or medicine. - Professor of the Institutes and Clinical Medicine: Benjamin Rush appointed January 23, 1792

During the last decade of the eighteenth century, death and retirement took many of these men from the faculty. When Hutchinson died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1793, the trustees voted to replace him with Dr. John Carson, who himself died the following year, 1794. Griffitts and Kuhn retired in the last years of the eighteenth century; Shippen gradually taught and practiced less and less. Rush, Wistar and Barton would remain, joined by the newcomer James Woodhouse.

Requirements and courses for medical students also underwent change with the reorganization of the new medical school under the University of Pennsylvania. On March 1, 1792, the Trustees abolished the M.B. degree and set out the new qualifications for the M.D. degree. All degree recipients now had to be at least twenty-one years of age and had to have studied medicine for a minimum of three years, with at least two years of this study taking place at the University of Pennsylvania. The required course included anatomy, surgery and midwifery; chemistry; institutes and clinical medicine; and practice of physic. A course in natural and experimental philosophy was also necessary, unless they had attended these lectures in another educational institution. In the year he was to graduate, a student was to be examined privately by the medical professors and then again by the University faculty and trustees; finally the candidate wrote a thesis on an approved topic, paid for its printing, and finally defended this thesis at the annual May commencement.