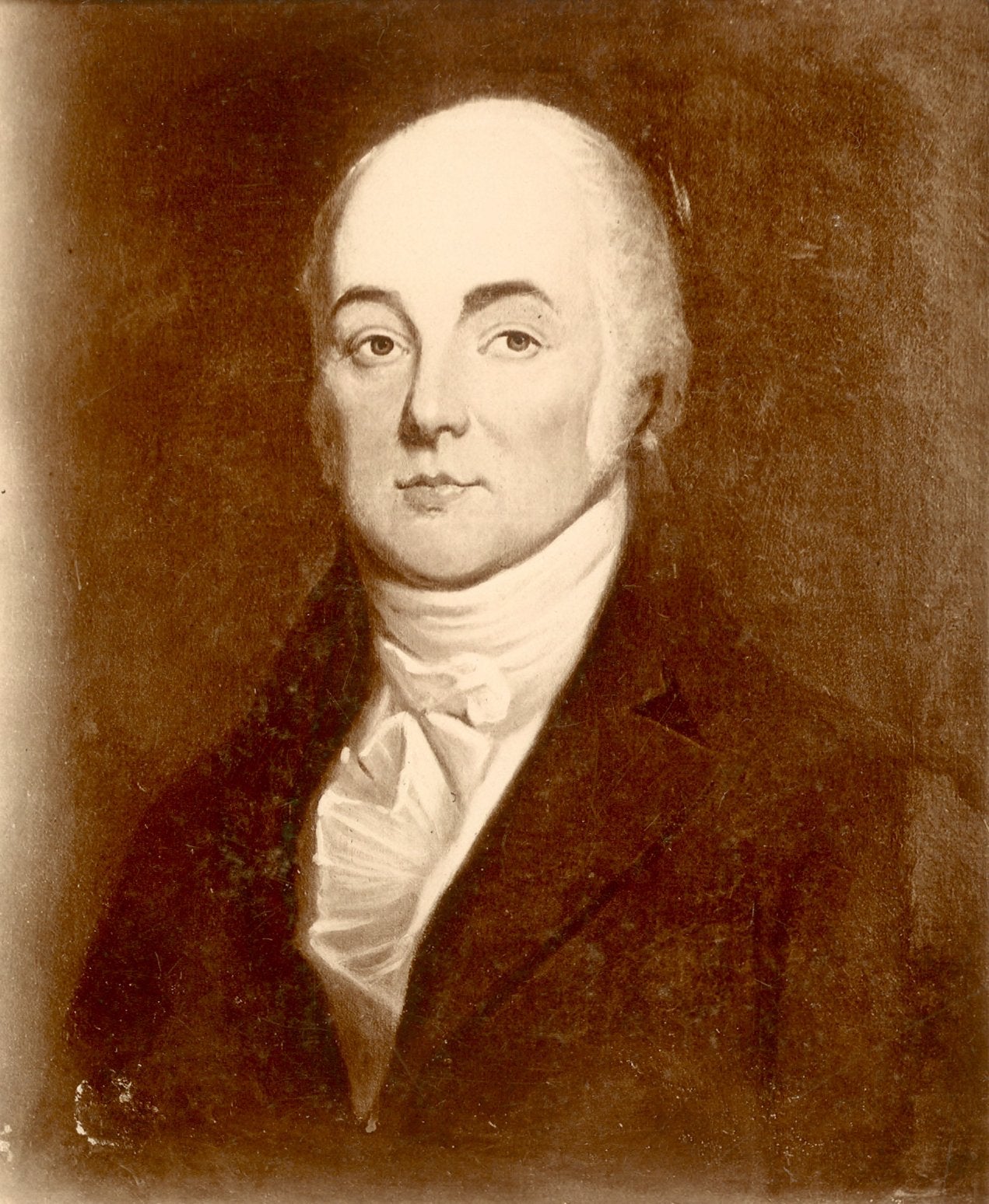

James Woodhouse was born in Philadelphia on November 17, 1770. He was the son of William Woodhouse, a bookseller and stationer, and Anne Martin. Woodhouse entered the University of the State of Pennsylvania in 1784, receiving his B.A. in 1787 and his M.A. in 1790. He studied medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush, and graduated from Penn’s medical school as Doctor of Medicine in 1792, at the first commencement after the 1791 union of the medical departments of the College of Philadelphia and the University of the State of Pennsylvania. Before finishing this degree, Woodhouse served in the army as a medical assistant, taking part in General St. Clair’s campaign against the western Indians in 1791.

While a medical student, Woodhouse directed his attention to the chemistry of medicine, in which he acquired a considerable reputation even before graduation. The title of his doctoral dissertation, “On the Chemical and Medicinal Properties of the Persimmon Tree and the Analysis of Astringent Vegetables,” suggests this attraction to chemistry. In 1792, Woodhouse founded the Chemical Society of Philadelphia, an organization of which he was senior president until his death. The society numbered seventy members over its years, with one corresponding member, Elizabeth Fulhane, in England. It had its own laboratory and published pamphlets on the analysis of minerals, ores and soils.

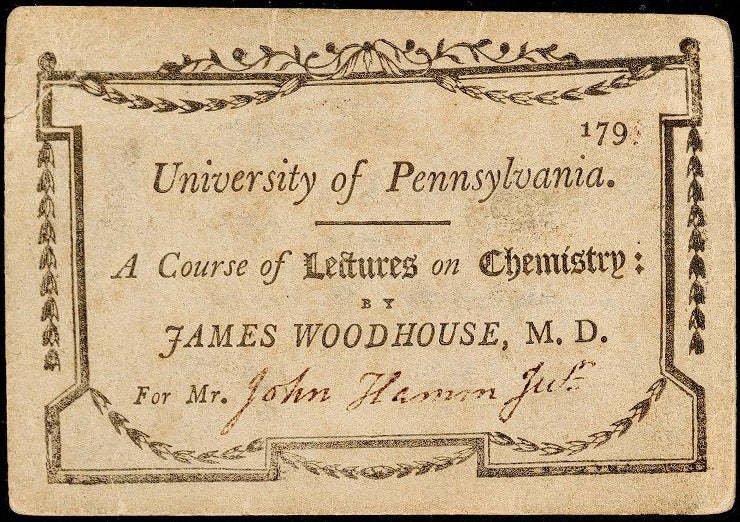

In 1793, the chair of chemistry at the University was left vacant by the death of Dr. James Hutchinson. In early 1794, it was conferred upon Dr. John Carson, a member of the board of trustees, but Carson died before he could occupy it. Dr. Joseph Priestley was then called to fill the position, but he declined, and a struggle ensued between Woodhouse and Dr. Adam Seybert, finally resulting in Woodhouse’s selection for the chair in 1795.

At the University, Woodhouse worked in a small but well-equipped laboratory, from which he produced a number of research findings and publications. Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen, was a frequent visitor of the laboratory. Priestley was an adherent of the phlogiston theory, believing in the existence of a flammable principle contained in materials that burn; Woodhouse, however, had produced some of the most telling arguments and demonstrations against the phlogiston theory. These were published in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, of which he became a member in 1796. After such presentations by Woodhouse and others, the phlogiston theory became effectively dead in the United States.

Woodhouse’s other investigations included the production of metallic potassium by carbon reduction, analytical determinations of mineral chemistry, observations on reaction of metals with nitric acid, demonstration of the superiority of anthracite over bituminous coal for industrial purposes, studies of corn and potato starch, and even a series of experiments in bread-baking.

Woodhouse filled the chair of chemistry at the University with great distinction until his death in 1809, when he was succeeded by Dr. John Redman Coxe. In general, his teaching was influential but received mixed notices. Benjamin Silliman, who came to Philadelphia to study with him, noted his “florid face” but complained that he was “wanting in personal dignity”. An anonymous commentator felt that he “lost much of his influence over his pupils, by neglecting the manner of communicating instruction.” It is possible that these criticisms merely reflected Woodhouse’s departure from the professional style of the period.

In 1797, Woodhouse published The Young Chemist’s Pocket Companion, a book of chemical experiments somewhat ahead of its time, since directed laboratory instruction was virtually nonexistent until well into the nineteenth century. He also edited American editions of James Parkinson’s Chemical Pocket-Book (1802), Samuel Parkes’s Chymical Catechism (1807), and the Elements of Chemistry (1807) of J.A.C. Chaptal de Chanteloup. His studies of plant chemistry produced Observations on the Combinations of Acids, Bitters and Astringents (1793) and Experiments and Observations in the Vegetation of Plants (1802).

Woodhouse was one of the few who helped establish chemistry as an academic and industrial study and instructed a generation of students in both the theory and practice of the discipline. He died of apoplexy on June 4, 1809, in Philadelphia. Some historians have speculated that his untimely death can be traced to a series of assays of the fuel values of various coals. These would have produced carbon monoxide, and the conditions in his ill-ventilated laboratory during the hottest summer Philadelphia had yet known may have hastened his death. Woodhouse never married.