Origins Under James Wilson

The Law School‘s origins can be traced to the founding of the Republic. In 1790 the first law lectures at Penn (then known as the College of Philadelphia) were delivered by James Wilson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence with Madison the major architect of the Federal Constitution, and one of the six original justices of the United States Supreme Court.

Justice Wilson “was commonly accepted in a nation already much dominated by lawyers as the most learned and profound legal scholar of his generation.” His lectures, presented in 1790 and 1791 at Penn’s first campus on Fourth Street, offered a wide-ranging comparative and critical analysis of legal systems past and present. Drawing upon epistemology and political theory, Wilson’s instruction included such diverse subjects as natural law, common law, and international law, and culminated in a close examination of the new American Constitution. Wilson’s lectures were not only detailed but remarkably farsighted. His ideas “more nearly foreshadowed the national future than those of any of his well-remembered contemporaries. None of them–not Hamilton, or Jefferson, or Madison, or Adams, or Marshall–came so close to representing in his views what the United States was to become.” The lectures were delivered to an audience of students and notables that included President Washington, Vice President Adams, and many members of the Cabinet and Congress. Wilson supplemented his lectures with moot courts and moot legislatures for the students.

The personal misfortunes of Wilson, a brilliant but paradoxical man, led to an early termination of his lectures and his untimely death. His observations on the purposes of legal studies are as applicable today as when he delivered them. He looked beyond the law to the most profound problems of human life. Wilson dismissed the concept of legal education as “disagreeable” or “perplexed,” wrapped in “a language unknown to all but those of the profession.” Instead, he described law an “historical science” based on “metaphysics” (by which he meant essentially what today is called psychology).

Wilson’s concept of law was harmonious with the philosophies of the College which Benjamin Franklin had founded some fifty years earlier. The University of Pennsylvania, both in law an in other disciplines, explored new horizons from its earliest days. The University introduced such subjects as applied mathematics, political science, and economics; it provided a multidisciplinary education before such a term existed. Beyond offering Professor Wilson’s law lectures, it established the first Medical School and developed the now-accepted concept of a teaching hospital.

George Sharwood Establishes the Law School

After this auspicious beginning, legal education at the University was neglected for more than half a century, until George Sharswood, in 1850, was elected professor of law. He originated a broad, two-year course of study embracing subjects such as international law, constitutional law, corporations, mercantile and real estate law, and jurisprudence. Two years later the Department of Law was formally established and the faculty expanded to three. Sharswood was named dean, a position he held until his elevation to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania eighteen years later.

In the Sharswood era, Pennsylvania’s law department was different from the modern Law School. Both faculty and students were part-timers. The professors were active practitioners who also taught law, until 1872 at Penn’s Ninth Street campus and then in College Hall on the new West Philadelphia campus. The students were either undergraduates or were serving apprenticeships in law offices during the period of their enrollment in the Law School.

Moving into the 20th Century

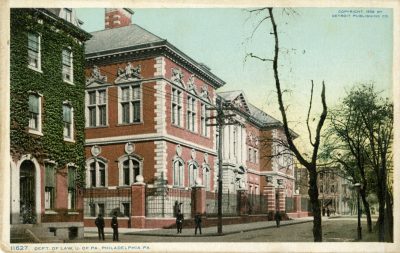

The modern era of the Law School began with the long and distinguished deanship of William Draper Lewis (1896-1914). The school was transformed from the law department to a modern professional school of high distinction. Immediately on becoming a dean in 1896, Lewis gave up his law practice and thus set the school on course towards a full-time faculty. Just two years later, in 1898, construction was begun on the Law School’s building on 34th, between Sansom and Chestnut streets.

At the end of his tenure eighteen years later, the number of full-time professors had increased to five and the total faculty from eleven to twenty-six. Another reform pioneered by Lewis (although formally adopted only after his resignation) was the requirement that applicants to the Law School hold college degrees. A few years later, Pennsylvania, along with Yale, became the first school to apply rigorous selective criteria for admissions. It was Lewis, too, who originated the idea of the American Law Institute, perhaps the nation’s most important agency for law reform. The Institute’s headquarters were in the Law School until 1948. ALI presently occupies offices a few blocks away.

Lewis’ able successors continued to advance the school’s reputation as a national leader of professional education. Added luster came to Pennsylvania during the deanship of Owen J. Roberts (1948-1952), former associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. His concern with public law was reminiscent of Justice Wilson’s.

He was succeeded by Jefferson Barnes Fordham (1952-1970) who, like his distinguished predecessors, Sharswood and Lewis, served for eighteen years. During his tenure, the Law School undertook pioneering projects in the behavioral sciences and underwent significant expansion in its faculty and physical plant. Dean Fordham’s accomplishments were not limited to his school; he set an example for active involvement in public affairs through his leadership in the reform of local government law and in founding and chairing the Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities of the American Bar Association. More recently the school has revised and broadened its curriculum, has begun a major drive to add to its endowment for scholarships, research funds, and library resources, and has added a vigorous international component to the institution.