Literary journal vs. chronicle of university experience

The earliest issues of the University Magazine contained long essays arguing in favor of “Book Worship” or describing “The Museum of Practical Geology.” Punctuated by rhetorical flourishes, and with a marked oratorical style that called for each piece to be declaimed, rather than read, the “literary” essays dominated the Magazine until the fall of 1879.

Sports news, university news, and communications to the editors had been present from the first, but took on greater prominence as the essay’s popularity waned. After the Magazine switched to a semi-monthly publishing schedule, editors no longer had to cram the results of every cricket match and football game of the last month into one issue; news columns from the law and medical schools were added to supplement the “Penn and Pennsyl Sketches” column, which consisted of tidbits of university news, announcements from the faculty, and notices from different class organizations.

It was common practice for collegiate newspapers and magazines to “exchange” issues with one another and write up a brief critical review to be published in the next issue. In September 1878, a mere three years into publication, the University Magazine acknowledged the receipt of some forty-three different college papers and magazines, including the Acta Columbiana, the Nassau Lit., from Princeton, and the Wittenberger, from Wittenberg College in Springfield, Ohio.

The exchange column shows the changing prerogatives of the University Magazine‘s editors over the years: while in 1878 the Exchange editor stated that “Owing to its not containing any essays it is rather hard to review justly,” subsequent editors after 1881 declared other journals too full of essays to be worth their time. The “Among Our Exchanges” column continued until the November 5th, 1883 issue, when it was declared that the Exchange column had become too much of a mutual admiration society to be of any use whatsoever, and that henceforth it would be combined with the “Other Colleges” column, and contain instead a synopsis of the news from other peer institutions, “with such brief comment as may be called for.”

From 1880 until 1884, the University Magazine also published short stories, usually either sentimental or satirical in nature. The four-part “A Hunt for a Provost,” published after Provost Stillé’s resignation in 1880, lampoons different “types” in American higher education: the foolish “aesthetic” professor at the University of Timbuctoo, located in very rural Indiana, the snobbish English expatriate who hopes to be able to split his time between Philadelphia and his newly acquired land in North Dakota, and the holier-than-thou Harvard professor, who can’t understand why anyone would ever go to a university that wasn’t Harvard.

After 1882, the tone shifted towards sentimental fiction, dominated by tales of old school chums meeting again after a great many years to discuss their adventures since their bucolic days at the old alma mater. Another common trope was the story of the avowed bachelor falling for a “charming” young lady, who was usually the sister of a college friend, or a friend of the family of a college friend. College ties and the joys of matrimony were the two predominant themes of these cozily domestic stories.

Curriculum Matters

Certain topics repeatedly drew the ire of the University Magazine‘s editors. In the late 1870s, after a brief period of staunchly defending the tenets of a classical education dominated by studies in Greek and Latin, the Magazine began to call for increased choice for students in their course of study. Within the department of Arts, juniors and seniors were permitted three “elective” courses, outside of the ordinary college curriculum. In 1877, juniors were required to take philosophy, physics, English composition, and organic and inorganic chemistry, with the choice of three other courses: Greek or German, Latin or French, and higher mathematics or history. Even with the choice of modern languages, the vast majority of students chose to continue in the classical languages. The Magazine took the position that it was illogical to present students with binary choices in three categories: what of the man with no interest in either Latin or French, but who was determined to study both Greek and German? Students should be allowed to put together any combination of three subjects to create a program suited to each man’s individual strengths.

The concept of an elective system was the major dividing issue of the day in American higher education. Under the leadership of President Charles Eliot, Harvard University embarked on a massive expansion of its undergraduate curriculum, even taking the step of dropping the Greek requirement for freshmen in the mid-1880s. The University of Pennsylvania took a more moderate path, offering a small degree of choice for juniors and seniors beginning in the late 1870s, and then progressing to the development of two separate degree tracks, one with instruction in the modern languages in place of Greek or Latin “after the close of second year,” and a second course “for those designing the study of Medicine,” which included the traditional subjects of Latin and Greek, but also included work in biology. Greek remained on the books as a requirement for an A.B. degree until 1915.

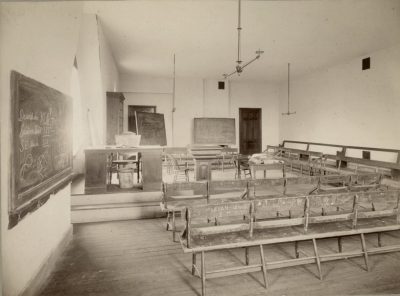

The Physical Campus

The Magazine editors were similarly concerned with the physical aspects of the university. After 1878, many students walked to class in the morning across the South Street Bridge; why was there no gate on the south-east corner of campus for their use? The cloakroom in the basement of College Hall had insufficient hooks for the students; could the University authorities not make some provision, either for more hooks, or, better yet, individual lockers for each man’s belongings? Occasionally pleas for change were made on the grounds of health and safety. In a letter to the editors published in March, 1885, a student called the attention of the faculty and students to the risks posed by the system of individually heating the recitation rooms:

“Some of our professors seem to like to get their rooms as close and stuffy as they can, while others are equally fond of the cold. This is very pleasant for the professors who stay in the same rooms all day, but for the students who go from one to the other, it is not only disagreeable but dangerous. The month, through which we have just passed, has been extremely trying in the way of colds and all other diseases that are caused by the changes in the weather.”

(March 5th, 1885)

College Regulations

The latter years of the University Magazine contain a sort of running fugue on the topic of compulsory chapel attendance. Although a secular university, Penn required its undergraduates to attend a compulsory chapel service in College Hall every morning before classes, much to the displeasure of the students. Juniors and seniors were required to give brief orations, and many university announcements were made; professors were not required to attend, which resulted in a large number of empty seats on the podium at the front of the room. The University Magazine editors argued that the service should either be made more spiritual and interesting, perhaps by the inclusion of music, or should be made optional. At the same time, however, they supported the actions of the faculty in trying to reign in the students and frequently chastised students who talked or did their homework during the service. On one occasion, the editors published a list of the worst troublemakers; on another they roundly condemned the man who tried to make the service livelier by introducing an irate chicken into the proceedings. While the official history of The Daily Pennsylvanian identifies the 1960s as the decade that gave birth to student engagement in activist journalism, the editors of the University Magazine maintained the right to agitate on behalf of the students and to respectfully question the decisions of the faculty and the trustees.

“Our platform is expressed in few words. It will be our endeavor to make the paper what it should be, the organ of the students. It will be run in the interest of the students and will be, as far as we can make it, the expression of their views.”

(20th January 1884)

Co-education

Co-education was also a sticky subject. The trustees of the University of Pennsylvania convened in the fall of 1882 to discuss whether it would be advisable to admit women to all the departments of the university; the Magazine reported the result as “an emphatic negative vote.” When a subsequent article in the Yale News claimed that “all departments of the University of Pennsylvania are now open to women,” (December 20th, 1882) the editors of the Magazine furiously denied the assertion, and then proceeded to publish a series of waspish comments about the dangers of college newspapers re-printing snippets of news about fellow institutions without bothering to check their facts. In the editorial responding to the Yale News, the Magazine declared themselves in favor of the education of women, but in separate, linked institutions such as the Harvard Annex, re-chartered as Radcliffe College in 1894. The idea of men and women taking the same classes, together, and participating on an equal basis in all aspects of university life was, however, simply unacceptable.

Although the University Magazine published communications to the editor which spoke both against and in favor of co-education, the Magazine itself was consistently opposed to co-education throughout its existence. However, the University Magazine exchanged issues with many co-educational colleges, as well as several women’s colleges; several “Exchange” editors were inclined to swoon over “our fair correspondents from the Lutherville Female Seminary.” In the issue for December 5th, 1882, the “Exchanges” editor noted that the Magazine had received a copy of the Delaware College Review and commended the publication for making a “very creditable showing,” despite originating, “as it evidently does, from a small institution, on which co-education has set its blighting seal. The hand of a co-ed is amusingly apparent in the first story…”

The editorial board could refute the possibility of co-education at Penn, and could quote the strong resolution passed by the men of Columbia in October 1882 declaring their opposition to co-education “on an educational, as well as from a social and a moral standpoint,” but the editors of the Magazine couldn’t deny that co-education existed and was gaining popularity across the United States. In 1882, the “Penn and Pennsyl Sketches” column noted “Nearly 200 out of the 358 colleges in the United States are co-educational.” (In the same issue, the “Medical Notes” column contented itself with publishing a brief quote from Provost Pepper’s inauguration speech in 1880: “I regard it as settled beyond dispute, that the co-education of the sexes is inadmissible.”) The land-grant state universities established by the 1862 Morrill Act were overwhelmingly co-educational; the majority of the state universities which pre-dated the Act were also co-educational by the start of the 1880s. Co-educational institutions were more common in the West and Midwest, but Swarthmore College, ten miles south-west of the University of Pennsylvania, had been co-educational since its founding in 1864. Nonetheless, a survey of Penn’s senior class in 1883 resulted in four men in favor of co-education—and twenty-six against. In its opposition to co-education, and in its defense of Penn as a male-only institution, the University Magazine was merely reflecting the prevailing attitudes of its editors, and the students, faculty, and trustees of the University of Pennsylvania.