Albert Monroe Wilson was born in October of 1841 on Spruce Street, between Eighth and Ninth Streets, in Philadelphia — only a few blocks from the University of Pennsylvania’s campus on Ninth Street between Market and Chestnut Streets. His parents, Albert Wilson and Frances J. Wilson, had also grown up in Philadelphia, as had their parents before them. After Albert’s family moved to Buckley Street (now Cypress Street) near Sixth Street, Albert attended Bird’s School on Sixth Street above Lombard and below Pine Street. Albert was consistently at the top of his class, but his formal education did not last long. Clashes between rival volunteer companies during the social unrest of 1850 sometimes led to riots, and during one of these free-for-alls, nine-year old Albert was hit in the head by a brick thrown by a rioter. The resulting head fracture and surgery left him with a lifelong scar and also ended his formal schooling.

The 1850 Census lists a household in the Pine Ward headed by Elizabeth Monroe (age 60) and including Hannah Pearce (age 33) and Frances Wilson (age 25) and her four sons: Iram (age 10), Albert (age 8), George (age 6), and Charles (age 3). All were identified as African Americans born in Pennsylvania. There is no mention of Albert Wilson, Sr. Apparently he was now dead and Frances Wilson, Albert’s mother, was now a widow with $3,000 of property. At the time of this census in the summer of 1850, both Albert and his older brother were listed as students, but not long after Albert entered the labor force. His first job was in a tobacco factory, but soon he found his life’s work at the University of Pennsylvania.

Albert Wilson began his employment in the College of the University of Pennsylvania in 1854, when he was only 13 years old. His career began as errand boy under the charge of the College “janitor,” first Francis Dick (died 1859) and then his brother “Major” Frederick Dick (1805-1875). Wilson would remain in the service of the University until his death fifty years later in 1904, serving under five provosts and outliving all other staff and students who had been part of the College when he first arrived.

Young Albert Wilson arrived on the Penn campus about the same time the members of the College Class of 1858 began their freshman year. Wilson endured some good-natured practical joking from students and sometimes became engaged in physical clashes with them, but the students soon became warmly attached to Wilson’s kind heart and merry nature. They also appreciated the tact and skill with which he balanced his loyalty to the University with his loyalty to the students. Wilson soon acquired the nickname of Pompey, or more often “Pomp.” Pomp had special affection for the College Class of 1858; not only were these students the first he knew for all four of their undergraduate years, they were also close to his own age. The Class of 1858 reciprocated his affection, naming him an honorary member of the class and always visiting with him when they returned as alumni. When the Class of 1858 put together Penn’s first class photograph, Wilson obtained a copy and hung it in his working quarters until the end of his life.

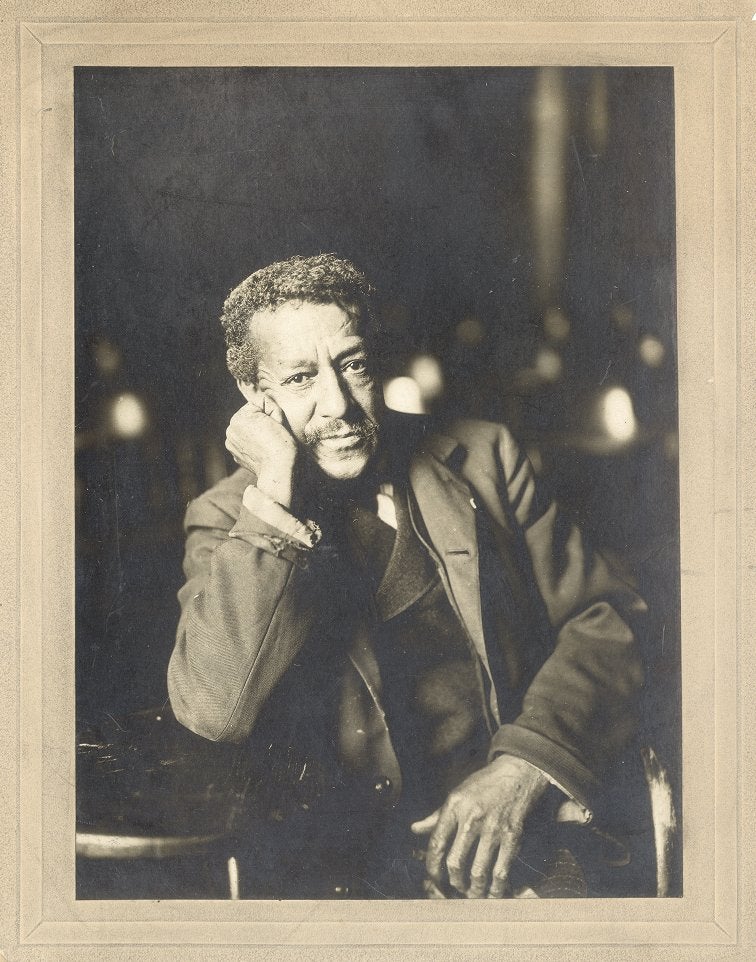

Although Albert Wilson was particularly attached to the Class of 1858, he became a key figure for all students passing through College Hall during his fifty years on campus. He and Major Frederick Dick are included in many of the earliest class photographs, in front of the College Hall on the old Ninth Street campus (see 1865, 1868, and 1871), and then on the new West Philadelphia campus in 1873. After the death of Major Dick, “Pomp” continued to appear in class photographs on the steps of College Hall or of the Library (examples are 1878, 1891 and 1892). Yearbooks from the late nineteenth century are also sources of information on Pomp, especially in the class history sections. In 1904, the year of his death, the yearbook included a special four-page section in his honor.

Wilson’s role at the University evolved over time. Under the supervision of the Dicks, he ran errands and did the menial work of keeping College Hall clean and orderly. In later years, Wilson succeeded the Dick family as janitor, locking and unlocking the doors to College Hall, ringing the College bell, lighting and extinguishing lights and fires (even for evening meetings of the Philomathean and Zelosophic societies), delivering mail and messages, and collecting lab fees from the students. Wilson rendered these services first at Penn’s Ninth Street campus and then at the new West Philadelphia campus. For some years, even after the opening of the West Philadelphia campus in 1872, he also had the duty of opening, closing, and maintaining fires at Surgeons’ Hall on Fifth Street, the original home of the University’s Medical Department which was later rented out for offices. These extra duties made his days so long that he often slept in a bunk in the basement of Surgeons’ Hall.

Professor John Fries Frazer (1812-1872), quickly recognizing Albert Wilson’s intelligence and reliability, made the young man his special assistant in place of the student assistants usually employed. Wilson was charged with setting up the apparatus and materials for lectures and experiments in chemistry and physics. He was sometimes enlisted as an assistant during Frazer’s experiments, sometimes barely escaping serious injury from unwanted explosions. After Professor Frazer’s death, Wilson helped Professor Henry Morton in his physics laboratory. Wilson pursued these scientific interests on his own, keeping several volumes on chemistry in his room at home.

It also could be argued that Albert Wilson was the University’s first archivist. After the 1872 move of the University to West Philadelphia, it was Pomp who secured the cornerstones from the Ninth Street campus and stored them in the sub-basement of the new College Hall; one of these, the cornerstone from the Presidential Mansion built in the 1790s, was incorporated into the entry of the library designed by Frank Furness and built in 1890. Wilson’s locked basement room, and then the clock tower of College Hall, housed other artifacts of College history as well. He stored more and more discarded furniture, apparatus, and materials that he thought might have value: old benches from Ninth Street, old locks and keys, leather fire buckets, various apparatus of faculty members.

Albert Wilson never married, instead devoting himself to the College. He was in attendance regularly from seven in the morning until later than seven at night, each day except Sunday. Wilson even came to work on holidays, except for New Years Day when he usually traveled to New York to purchase a suit. In later life he lived with family members at 1130 Lombard Street. The 1880 census lists this Lombard Street household as headed by Albert’s widowed mother, Frances Wilson, age 55. Also in the household were Albert (listed as a 38 year old messenger). Albert’s brothers Charles H. (a 30 year old messenger) and George H. (a 36 year old shoemaker), and George’s wife Anna and their two three-year old sons, George and Charles. Two of Albert’s other brothers, William and Jacob (both barbers, ages 27 and 26 respectively) lived in the rear of the house next door, along with William’s wife Emma and his three children Clarence (age 7), William Jr. (age 4), and Celestine (age 3).

Twenty years later, Albert was still living in the same house with his brother George and his family. The 1900 Census lists this African American household as headed by George H. Wilson (born 1845) and his wife Anna M. Wilson (born 1847), along with George’s unmarried brothers Charles H. (born 1852) and Albert M. (born 1841) — the man known at Penn as Pomp. As in 1850, all are listed as born in Pennsylvania to parents who were also natives of Pennsylvania. Also in the household were George Wilson’s widowed mother-in-law (Ruth Campbell, a cook) as well as his three sons and two daughters — Albert Wilson’s nieces and nephews. The members of this youngest generation, ranging in age from ten to twenty-two years, were the young girls Anna M. and H.B. (both still in school) and their brothers: mailman George H., Jr., artist Charles H., Jr., and laborer Albert, Jr.

In 1904 alumni rallied to plan “Pomp’s Jubilee” to coincide with commencement week in June of that year. Public ceremonies were planned and considerable money was raised with the intention of using the income to provide retirement income for Pomp and then, after his death, a scholarship fund in his name. The “Albert Wilson Scholarship, founded by the Alumni of the College of the University of Pennsylvania in memory of a faithful servant and loyal friend.”

Unfortunately, Albert Wilson died of pneumonia on Saturday, March 9, 1904, several months before this public recognition was to take place (and just two weeks before the death of athletic trainer Samuel White, another African American figure familiar on campus in the late nineteenth century). Although he had not been in the best of health for the last year or so, he had continued to work his usual long hours. It was not until the Thursday before his death that the concern of those in College Hall convinced him to go home sick early in the afternoon.

Albert Wilson was buried from College Hall with all the affection and respect the University could provide. On Tuesday morning, the honorary pallbearers, drawn from the junior and senior classes, accompanied the hearse from 1130 Lombard Street to College Hall. Students assembled by class to participate in the viewing along with hundreds of alumni. At 2 p.m. the funeral service took place in the College Hall Chapel, filled with flowers and a standing-room-only crowd of faculty, alumni, students, and others. Rev. Dr. Jesse Y. Burk, secretary of the trustees and a friend of Wilson, read the service. Penn’s professor of music played the organ to accompany the University’s best singers. The body was then carried from the Chapel as the college bell tolled fifty times, one stroke for each year of Albert Wilson’s service to Penn. Wilson was buried in Merion Cemetery in Cynwyd.

Faculty members and students alike recognized Wilson’s devotion to the University and the depth of his knowledge about how it functioned. At times Wilson could be crusty or stubborn, but only when he felt others were not doing the right thing by the University. Everyone valued Pomp’s friendship; students and faculty remembered with pride the first time Pomp called them by name. He was memorialized in 25 pages of reminiscences printed in the Alumni Register of April 1904 as well as in the 1904 Record. The many tributes echo the sentiments expressed by Persifor Frazer, A.B. 1862 (the son of the Professor John Frazer who first took on young Albert Wilson as laboratory assistant) at the end of his memorial:

He was brave and intelligent, loyal and true, affectionate and proud. He devoted his sole and only treasure and inheritance to the University of Pennsylvania — his whole life.