In 1864, George B. Wood single-handily brought “science” back into Penn’s medical curriculum. Wood, who retired from teaching in 1860, remained active in the Medical School’s administration. One of Penn’s first supporters of “science,” Wood encouraged the teaching of natural sciences. Although the Medical School employed two of America’s leading scientists, Joseph Leidy and Alfred Stillé, it did not teach basic science. George B. Wood donated $50,000 to endow 5 chairs in zoology, botany, geology, hygiene, and medical jurisprudence. Each member of the auxiliary faculty delivered 34 lectures, and students were not required to attend in order to graduate. Wood’s endowment allowed students and graduates of the Medical School to attend lectures for free. This broadened curriculum provided students with a better understanding of science and medicine. Later courses in bacteriology and microscopy evolved from these auxiliary lectures. Wood’s reforms did not immediately spark transformations throughout Penn’s Medical School. Until the mid-1870s, the faculty did not receive salaries and the mandatory curriculum focused on medicine and clinical practice. But George B. Wood’s initiative did lay the foundation for more widespread and radical reforms in 1876 and 1877.

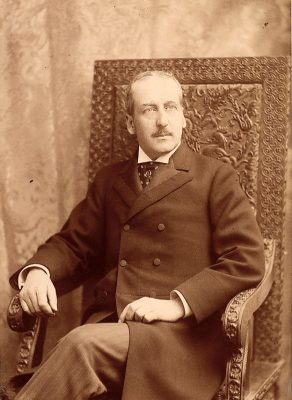

William Pepper, Jr., a talented physician and administrator, reignited the spirit of reform within the Medical School. An 1864 graduate of Penn, Pepper believed medical education needed more clinical instruction. Even though Pennsylvania Hospital and other dispensaries provided patients for students, “their aims did not fully coincide with those of the school.” In 1870, Pepper campaigned for the construction of a medical hospital in West Philadelphia, which would be directly affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. Pepper successfully acquired donations from 109 prominent citizens, $200,000 from the Pennsylvania legislature, and $250,000 from the University. On June 4, 1874, the University of Pennsylvania Hospital opened and became the first university-affiliated hospital in America. Alfred Stillé, D. Hayes Agnew, and William Pepper gave lectures in the hospital’s amphitheatre, and provided bedside instruction in its various wards. By constructing the hospital, William Pepper initiated Penn’s move to West Philadelphia, advanced medical instruction, and ended the era of inactivity within the Medical School. The University’s financial support gave the administration a newfound control over the Medical School.The University’s Board of Trustees forced the Medical School to change its outdated curriculum and financial structure. The medical faculty sacrificed much of its autonomy in order to secure the University’s $250,000 investment. The University’s trustees appointed a special committee to assess the Medical School’s structure, and ultimately suggest reforms. On March 28, 1876, this special committee presented a printed report offering major changes within the Medical School. Their reforms included: a course length of three annual terms of 5 months, a fixed salary of $3,000 for faculty members, a graded curriculum, and an addition of four new chairs to the Medical faculty. These necessary changes followed the models created by Harvard and George B. Wood a decade before. The medical faculty supported changes to the curriculum and financial structure, but opposed the addition of clinical chairs. The trustees sought to unite the Medical and Hospital faculties by adding chairs in clinical surgery, clinical medicine, diseases of women and children, and pathology. Robert E. Rogers, the Dean of Faculty, argued that the reform placed “teachers of several special and subordinate subjects upon an equality with the professors, who teach branches of medicine which include those very subjects.” Despite Rogers’ opposition, the trustees implemented all of the proposed reforms in the fall of 1887. An infuriated Rogers resigned and accepted the chair of chemistry at Jefferson Medical College. In a sign of support for clinical instruction, or from indifference, the other faculty members welcomed the additional chairs “without open demur.” New attitudes and University control restored the Medical School’s reputation as a leader in modern education and research.

Thirty years after the reform of 1847, the Medical School once again assumed the responsibility of advancing medicine and science. European discoveries developed pathology, hygiene, microscopy, and bacteriology into popular and significant fields. Throughout the 1880s, the Medical School added pathologists, hygienists, and bacteriologists to its faculty. James Tyson, Penn’s first chair of pathology, taught required laboratory courses in microscopy and morbid anatomy. In 1884, Tyson and his colleagues persuaded Canadian pathologist William Osler to accept the chair of clinical medicine. Osler succeeded Joseph Leidy as Penn’s most renowned researcher and public figure. He gave bedside instruction, taught students to look for microscopic parasites, and “brought a fresh scientific outlook to the practice of medicine.” Osler’s presence on the medical faculty cemented Penn’s position at the top of the medical ranks. William Pepper, Jr. focused his administrative attention on constructing new laboratories and medical buildings. In 1888, Pepper used his own money, donations, and University funds to construct a laboratory for the School of Hygiene. The General Laboratories Building, located on 34th and Spruce streets, opened in 1892 for the specific purpose of hygienic and bacteriological studies. To accompany this teaching facility, Pepper constructed a laboratory for medical research.