Penn’s undergraduate and graduate metamorphosis was complete by the late sixties and by the early seventies the University had devised an overall scheme by which to attract more applicants but constrain the number accepted, in order to become more selective academically. Football had also been inhibited since the Ivy League agreement and Penn had been losing the majority of its games in the sixties and seventies as penance to compensate for its history of frequent transgression of the Ivy League athletic ordinances. Despite the structural handicap, the football program would slowly but surely climb out of the doldrums of failure and achieve success in the Ivy League in the eighties. As expressed (and perhaps implemented) by Dean Owens, Penn’s athletic program was more or less severed from university image and Penn’s administration and faculty continued to distance itself from the program through apathy. But academics and football were only two parts of Penn’s complex image; what of fraternities and student life, how was this aspect of the university progressing in the sixties?

Fraternities had transformed with the larger evolution of the University as it moved toward the academic life along with an egalitarian and diverse social ethos. The fraternities (who had been undeniably non-academic and discriminatory by nature) remained under scrutiny by administration and faculty whose prime concern was scholastic achievement among the students. The fraternal GPA (grade point average of all of the fraternities combined) did not help the fraternities in their effort to stay afloat. In an article published in February of 1965 by the Daily Pennsylvanian, Penn’s daily newspaper, several devastating facts of the 1961-62 academic year one of which was particularly potent: the fraternal GPA was a 2.33, which is equivalent to a C+. In 1963, it rose to a 2.4, yet the fraternal GPA was consistently lower than the All-men’s average. Guy Anselmo, the assistant Dean of Men at the time stated: “It [the fraternity] seeks as a part of its college, to promote diligent application to study by a fraternity member, not only in order that the requirements of the college be met, but also that achievement above average level may be maintained.”

Not only were fraternities remaining rather lackadaisical in terms of academics, they were all but they were also reprobate in achieving racial integration into their houses. Various articles of local newspapers from the early to mid sixties show the administration’s difficulties in fostering now mandatory fraternity policies for pledging in a more non-discriminatory way (if such a thing is actually possible in a fraternity). The “frat” brothers were evidently not pulling their load academically, while at the same time producing bad publicity through purported discrimination.

And this led to another reality: fraternities were hindering Penn’s bid for true academia. Dr. E. Digby Baltzell, a professor of Sociology was quoted in the same article by Anslemo in which Baltzell, “expressed his desire to see the fraternity system contribute toward ‘a more intellectual tone’ at Penn.” The University could not very well cut out “frat” houses altogether, as Dr. Baltzell points out, “Fraternities are one of the best ties which the University has to contributing alumni.”

But with glares from the faculty and administrators, there was one major asset that fraternities offered which was beneficial to Penn: housing. In 1964, when 740 of Penn’s 4200 undergraduate men were in fraternities, it was said, “The University of Pennsylvania places a greater proportional weight on fraternities to provide housing.” As Penn’s academic standards were rising, so did Penn try to instill this in fraternities. The proposed “House Plan” of 1965 was a plan to be initiated in the fall of 1970 consisting of uniting the faculty and undergraduates through a house holding 300 students each. This would provide more residential housing for the undergraduates and distance Penn from the once vital fraternities.

By insulating its image from the fraternities, Penn was also repudiating the moribund fraternities, which could not survive the decline in pledges owing to the “House Plan”. Tom Lang, president of the Men’s Student Government summarized the general mien of the University towards the fraternities at the time, “Those houses which survive will be the strongest. The others will die.” And in order to sound a bit more optimistic, he added, “Overall it will improve fraternities because of the weeding out process.” This was an accurate statement, yet without mass representation, fraternities lost their significance to Penn and became fringe groups, holding out against the lifestyle of the general student.

The University, as it passed through the bracing times of the sixties, became increasingly egalitarian and pluralistic. The University had become increasingly diverse as its undergraduate student body expanded. Along with more emphasis on intellectual consideration, Dean Owens had mentioned diversity of the student body as a priority.

In 1969, a total of 45 fraternities and sororities existed on the University of Pennsylvania campus , but in 1972, three years after the “House Plan’s” inaugural year, 27 Greek organizations remained. In the coming years when reports of fraternity antics surfaced, Penn’s fraternities inspired nostalgic anecdotes rather than real concern. They were more or less detached from the University and became as marginal as at any other Ivy league school. Penn’s fraternities experienced publicized episodes of drinking and hazing, but nothing to draw national attention.

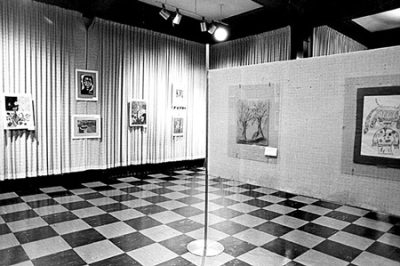

In the seventies and eighties, Student life became more inclusive and egalitarian after the virtual disappearance of fraternities from general student activities. Art exhibitions, musical performance, and comic and satirical sketches were publicized in local newspapers. Penn gained at least regional attention for the rich theatrical program at the University. Reruns of football games and “invitation only” fraternity/sorority galas no longer dominated the social schedule at Houston Hall. Rather in the mid and late seventies, academic clubs and performances predominated as the most common activities that transpired in university facilities.

Student life had shifted its role in the University: student life was now University life, as many of the student events gained attendance from a local entourage or “non-university” persons who accompanied students, faculty, and administrative figures to University presentations, lectures, and events of general public interest. Student Life expanded its significance at Penn and augmented Penn’s image of a diverse student body.