The first fraternity, Psi Upsilon appeared in 1849 and throughout the next six years three more fraternities gathered in various places on Penn’s campus. After twenty-five more years, shortly after Penn’s movement to West Philadelphia, the University gained four more. Then from 1890 to 1920 an eruption occurred: on average a fraternity would emerge almost every year. The first fraternity house was built in 1897 when Psi Upsilon house was erected on 300 South 36th Street. Following this, fraternity houses went up rapidly in the very early 1900s. In 1898 there were 20 fraternities; by 1928, the campus was crowded with Greek societies: 73 resided on campus; 17 of them sororities.

When they came onto the University scene in 1849, the fraternities had been a source of aggravation to the local literary clubs because they sapped membership the once-popular clubs that had preceded them. But to the further dismay of the old literary clubs, fraternities at Penn began to play a somewhat distinguished role at the University.

At first, fraternities served merely as a source of social interaction and brotherhood, but with the involvement on the part of the United States in the First World War, fraternities were leased to the Students’ Army Training Corps, to enable the young men of Penn to receive military training before enlistment. Fraternities ceased its well-known image of association with social and political issues in 1925.

After 1925, the administration and others attentive to the current issues of the University began to regard Penn’s fraternities as essential the financial and residential well-being of Penn. This change occurred when the University instated the “Fraternity-Dormitory” plan, in which Penn bought land around fraternities in order to have supplemental control of them. The property-value of the fraternity houses had grown during the twenties and consequently so did the taxes for the area. Thus, by transferring the property titles to the University the fraternity houses could be claimed as “real-estate used for educational purposes,” becoming tax-exempt. The University’s claim did not stand, however, as the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce opposed the tax-exemption of fraternity houses queried by the university in 1926 (eventually Penn was allowed tax exemption by the city in 1939, on properties valued at $200,000, when 25 of Penn’s fraternities paid no real-estate tax that year ). After they had subsidized the fraternities, the university endorsed the houses as dormitories to compensate for the lack of residence halls.

Unfortunately, this “ownership” could not inhibit the antics of some of the crazier fraternity houses. A notorious example of this came on April 17, 1926, when a “Dance” sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania fraternities was held in honor of some of the Beaver College women students. Reports of “drunkenness” and general scandal were all over papers nationally. Beaver College (now Arcadia University) women were forbidden to further attend Penn soirees. Penn’s fraternities acquired a reputation that was less than savory as far as the administration and faculty were concerned.

In 1948, fraternities continued to play a prominent role at the University. The fraternities exercised a strong, pervasive role in undergraduate life. There were many fraternities (or sororities) that covertly described themselves as belonging to one denomination or another (Christianity or Judaism). Other fraternities while not exclusive (or discriminatory) in a religious faith, were renowned for their academic or extra-curricular interests, such as Delta Upsilon in athletics, Alpha Sigma Phi for their publication, “The Tomahawk,” and Phi Sigma Delta for scholarship. And with so many fraternities, it is not surprising that many people could find their place among the “elite,” fraternities housed 39.4% of the male undergraduate population, the 14 sororities housed 31% of the undergraduate female population; and combined they accounted for 38% of the full-time undergraduate populace at Penn.

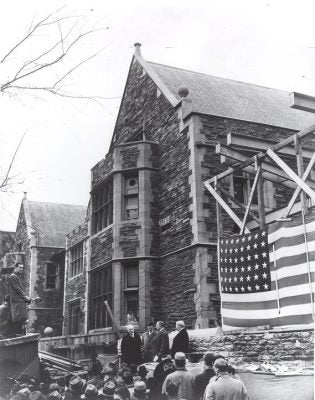

Alongside fraternities, there were alternatives for the undergraduates to the social and political life of the Greek societies. Houston Hall, America’s first collegiate student union, provided social events (such as movies and dances), student business appropriations (post office and student bank) , and an area for the student government associations. Houston Hall was established in 1896 by Henry Houston, a notable railroad official of the late 19th century. The Hall remained the center of student life through the 20th century, serving as the favorite place to eat or read. With the enlargement of 1938, the already famous facility became a haven for constructive, non-academic activities on campus. One of the most popular aspects of Houston Hall for Penn undergraduates was the weekly showings of the Saturday football games recorded at Franklin Field–or elsewhere when the Quakers were away.