As Article II of its constitution stated, “the object of [the Houston C]lub [was] to draw together students, officers, and alumni of all Departments of the University in a wholesome social life, and to provide for them suitable amusements and recreations.” In order to achieve this goal, the Houston Club’s constitution clearly laid out the leadership structure and methods of operation.

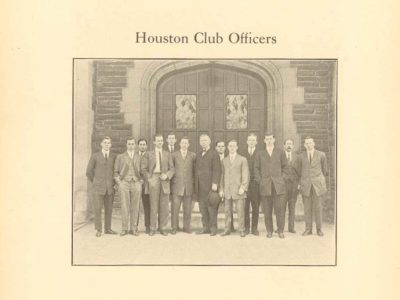

The club had five officer positions: the President, the Vice-President, and the Recording Secretary were elected officers; the Secretary and the Treasurer were appointed by the Board of Trustees of the Houston Club one week after the Board announced the election results. Any member of the club was eligible for any of the officer positions, the only exception being that the president had to have been a member of the club for at least one year before he could run for that office.

Three standing committees also governed the club: the House Committee, the Membership Committee, and the Library Committee. The House Committee was in charge of maintaining Houston Hall and its non-literary contents, such as pool tables and chessboards. The Membership Committee oversaw the admission of new members to the club and the Library Committee was in charge of all the books, magazines, and other reading materials in the Club’s possession. In an attempt to increase the scope of the Houston Club’s democratic influence on campus, the club’s constitution mandated that each standing committee consist of two members from the College and two from each of the seven graduate and professional schools, as well one member of the faculty.

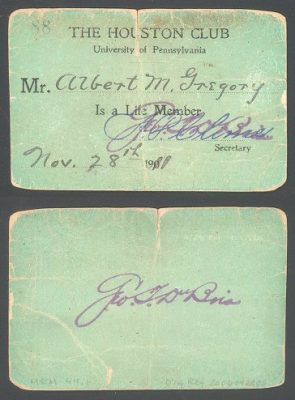

The House and Membership committees had the power to suspend or expel club members for disobeying house rules, but it was the Membership Committee that was most able to influence the Houston Club’s future. To become a member of the Houston Club, a student had to fill out a form and pay the Club’s dues. When the candidate completed an application for admission, it was posted in a visible public space in Houston Hall. There the application would remain for one week so that all club members could have a chance to inspect it. If no club member objected to the applicant or his application, the applicant would be admitted to the club at the conclusion of the week. If an objection was raised, however, the application would go to the Membership Committee which had the final say regarding the admittance of the applicant. In this way the Membership Committee, by excluding certain students from the Houston Club rolls, could alter the future nature of the Club and also deny those students the opportunity to participate in student government at Penn. Essentially the Membership Committee had the power to “black ball” students from their government.

Members of the Houston Club exercised their democratic privileges by voting for representatives of their class as well as their school. Candidates for the elected officer positions had to be nominated by members of their class while candidates for the committee positions had to be nominated by students in their school. Each class was permitted to nominate no more than three candidates for each of the elected officer positions and each school was permitted to nominate no more than five candidates for the two spots representing that school on each committee.With the nominations completed, the Club could proceed with its elections. Students in each school were permitted to vote for their representatives for committees and the entire club membership voted for the elected officer positions, regardless of the class year and the school department of the candidates or the voter. On a set day in April, the polls in Houston Hall were open from nine in the morning to six at night and all members were highly encouraged to submit their color-coded ballots for committee and officer elections.

Although those who were allowed to participate in the Houston Club’s electoral process were a part of Penn’s democratic student governance process, there were, however, students who were not able to share in this democratic process. Membership in the Houston Club was a prerequisite for participation in the election of class officers, either as a voter or as a candidate. Students who could not participate in the democratic process included those students who the club’s Membership Committee deemed not suitable for membership in the Houston Club, those students who could not afford the Houston Club’s fees, those who did not see the need to join the Houston Club, and women. The club was so staunchly against the inclusion of women that the constitution forbid women to enter certain parts of Houston Hall and mandated that all women be accompanied by a club-member host at all times when they were in Houston Hall.

Those Penn students disenfranchised through their exclusion from the Houston Club could only hope to gain a say in student governance through amendments to the Houston Club’s constitution allowing for their membership. The process for amendments to the Houston Club constitution was, like the club’s democratic privileges, restricted to club members.If a member proposed an amendment to the constitution, the amendment had to be posted in a visible public place in Houston Hall, for one month before it could be voted upon. The amendment had to receive approval from two-thirds of the club’s members to pass and become a part of the Houston Club’s constitution.

Over the years, the number of students who could not become members of the Houston Club and participate in student governance at Penn was reduced. At the beginning of the 1922-1923 academic year, the Houston Club membership fee was included in the tuition for all University students as a part of the “General Athletics and Houston Club Fee.” This change made it so that all tuition-paying male students were now a part of the club and able to vote in its elections. At the beginning of the 1925-1926 academic year, Bennett Hall (now Fisher-Bennett Hall) was opened. Bennett Hall was essentially a women’s version of Houston Hall, a space in which female students would socialize and relax. Bennett Hall, just like Houston Hall, was governed by a student organization; in this case it as the Bennett Union Board (BUB).

As access to Houston Hall became wider-spread throughout Penn’s student body, the Houston Club became unnecessary and on June 6, 1929, it was replaced by the Houston Hall Board, an organization open to all male tuition-paying Penn students. The Houston Hall Board (HHB) was open to a far wider range of students than the Houston Club and dealt only with Houston Hall and events held therein.In December of 1969, HHB and BUB, merged to form the Penn Union Council, an organization which performs essentially the same duties as today’s Social Planning and Events Committee. The establishment of the HHB and the BUB coincided with the establishment of the Undergraduate Council as Penn’s first organization with the sole focus of student governance.

Even though the Houston Club was clearly not an entirely democratic organization, it laid the groundwork for a future of democratically-run student government organizations at Penn. The Houston Club also demonstrated that undergraduate students were more than capable of choosing their own leaders who were themselves quite capable of handling undergraduate affairs while making mature decisions. If not for the Houston Club and its well-managed and smoothly-run executive board, it is unlikely that Penn’s administration would have allowed future student government organizations to become as powerful as they were to become.