The course of study required to earn an M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1889 was based on at least three years of courses, reflecting the major changes in curriculum during the two decades after the Civil War. A fourth year of study had been added to the curriculum in 1883; although students were encouraged to take this course after earning their degrees, the few who enrolled in the late 1880s were doing postgraduate work. A full description of three-years of course work, including course rosters and text books, is found in the University Catalogue for 1888-1889. As can be seen in the analysis below, medical students in the Class of 1889 clearly had the opportunity for a medical education that combined academic knowledge in basic and specialized areas of medicine with plenty of practical experience in the laboratory, dissection room, the patient’s bedside and even the operating room.

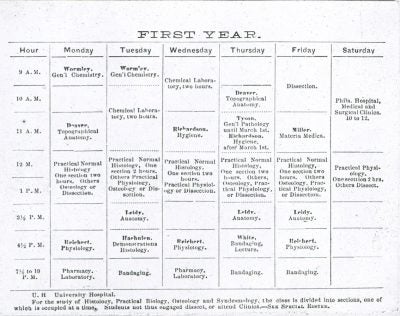

First Year

During the first year of study, course work emphasized the basics of anatomy (including topographical), chemistry, histology, physiology, materia medica and pharmacy. Students also attended a one-hour weekly lecture on general pathology and another on hygiene. Students also attended general medical and surgical clinics.The weekly schedule consisted of 15 hours in lectures, 4 hours in clinics, and 19 hours in laboratories or practicums. In 1886-1887, 38 hours total were scheduled each week; by 1888-1889 an extra half hour of lab would be required of first-year students.

At the end of the year examinations were given in general chemistry, osteology, histology, materia medica and pharmacy, and elements of general pathology.

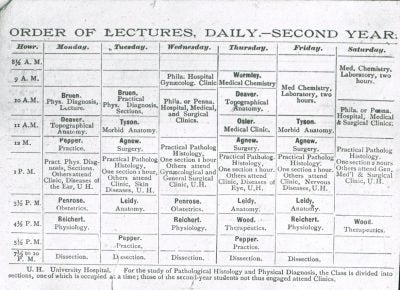

Second Year

In the second year of study, both courses and clinics became more specific and also more time-consuming. For students this year was most memorable for the ten evening hours spent in the dissecting room each week.Courses covered anatomy (including morbid as well as topographical), medical chemistry, pathology, physiology, theory and practice of medicine, surgery, obstetrics, physical diagnosis, and therapeutics. Clinics dealt with nervous diseases, gynecology, and diseases of the skin, eye, and ear.

This work involved a weekly schedule of 22 hours in lectures, 13 hours in clinics, and 16 and a half hours in laboratories or practicums – 51 and a half hours total.

At the end of the year, examinations were given in anatomy (including topographical), medical chemistry, and physiology.

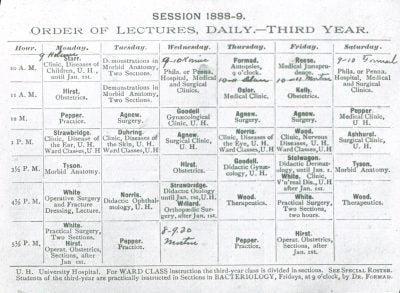

Third Year

In the third year, instruction became even more specialized. Anatomy and pathology were extended to include autopsies. This was also the year when students began to work with real, living patients in surgery and at their bed sides.Course work was devoted to obstetrics and operative obstetrics, general pathology and morbid anatomy, surgery (including operative and minor), theory and practice of medicine, gynecology, therapeutics, ophthalmology, otology, and dermatology, plus medical jurisprudence and toxicology. Clinic time was split between general clinics (medical and surgical) and special clinics (nervous diseases, pediatrics, gynecology, and diseases of the skin, eye, and ear). Bedside instruction in medicine and surgery was added this year.

Each week students were to spend 19 hours in lectures, 16 and a half hours in clinics, 2 hours in demonstrations, 3 hours in practicums and 3 hours in bedside instruction – a total of 43 hours per week. Clinics were conducted at both University Hospital and Philadelphia Hospital. Philadelphia Hospital, also known as Blockley Hospital and later as Philadelphia General Hospital, was located south of the University Hospital on the grounds of the Alms House.

Final examinations covered general and special pathological anatomy, therapeutics, theory and practice of medicine, clinical medicine, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics; at least one question involved the diseases of the skin, eye and ear chosen from questions submitted by the clinical professors of these specialties.

Graduation

At the end of the third year of successful course work, a student was awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine if he was at least 21 years of age and of “good moral character”, had passed all examinations in all branches of instructions and had attended the practical instruction in all departments (his last course were required to have been in Penn’s medical school). It was also necessary that, unless excursed by the faculty, he be present at commencement. A fourth year of attendance was recommended, but not required and the requirement of preparing and defending a thesis was no longer in effect.

The requirement of preparing a thesis in order to receive the M.D. degree was effectively abolished in April 1885. In November 1884, the Provost had suggested to the faculty that the thesis be dropped in favor of students preparing reports on clinical cases at the end of each year of instruction. The matter was referred to a faculty committee that included Sir William Osler (who was then at Penn) which agreed with the idea of dropping the thesis but could not come up with any plan for a clinic report requirement. The faculty made the final decision in April 1885 to remove the requirement but allow students to voluntarily prepare theses which would be used to award prizes at graduation.