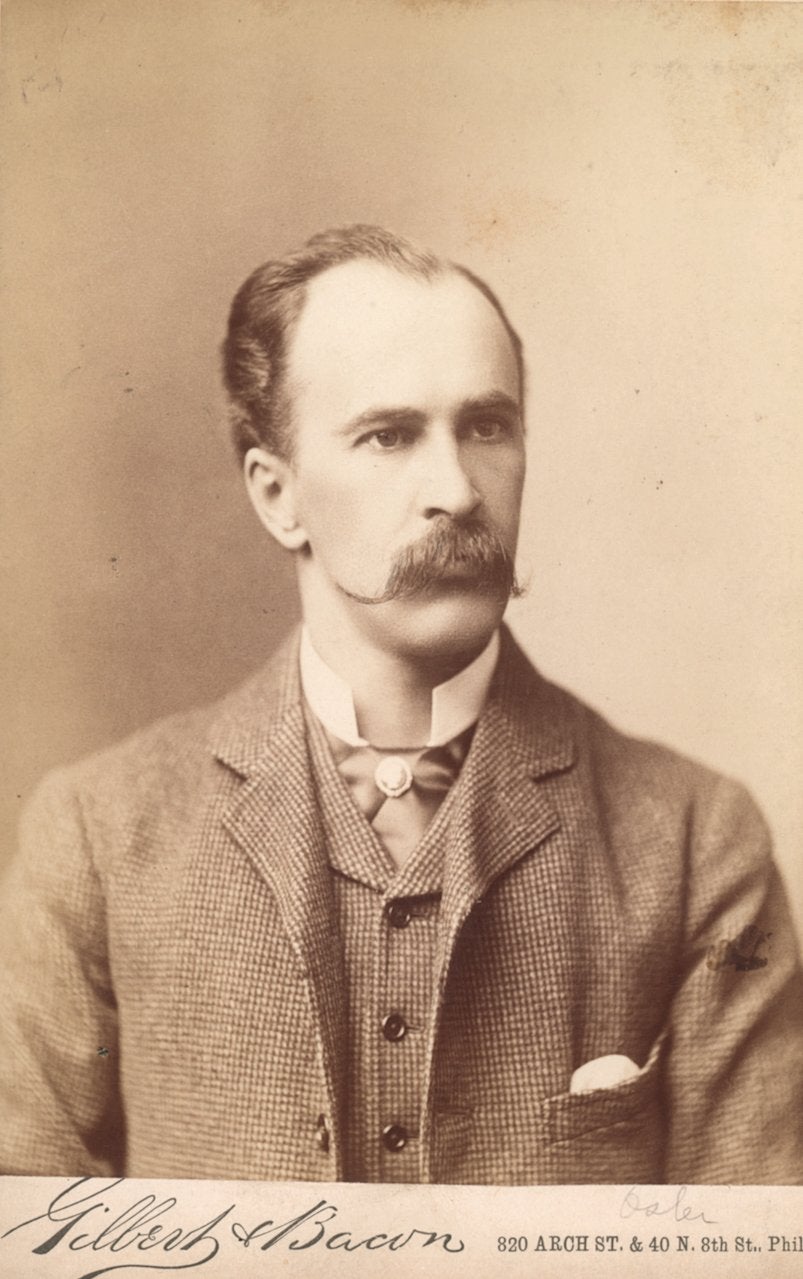

William Osler, physician, educator, and medical historian, was born in Bond Head, Ontario, Canada, on July 12, 1849, the son of an Anglican priest, Featherstone Lake Osler, and Ellen Free Pickton, both of Cornwall, England. As a young scholar in the backwoods of early nineteenth-century Ontario, Osler was increasingly torn between his commitment to science and religion. His interest in science eventually triumphed, nurtured by the guidance of another Anglican priest, Reverend W.A. Jackson, who encouraged Osler to study natural science. Despite his early commitment to science, Osler was exceptionally well read; at home, he delved into religious writings and classical literature.

In the autumn of 1867, Osler began his formal education at Trinity College in Toronto where he initially planned to study divinity. That course of study, however, was extremely short-lived; within one year, Osler switched to medicine. After two years at Trinity School of Medicine, Osler transferred in 1870 to McGill Medical College in Montreal, where he obtained his medical degree in 1872.

Following graduation, Osler decided to become an ophthalmologist. At the time, postgraduate study in medicine was casual and haphazard; Osler spent two years traveling Europe and studying intermittently with other scientists in London, Berlin, and Vienna. His experiences abroad would later make him as much a part of European as American medicine. Osler returned to Canada in 1874 with no medical position and no means to support himself. He moved back into the family home in Dundas and briefly worked as a general practitioner and a locum tenens for a physician in nearby Hamilton.

When McGill offered Osler a position as lecturer in the Institutes of Medicine in 1874, he immediately accepted the opportunity and moved back to Montreal. After that initial year of teaching, Osler’s prestige as an instructor, and later a professor, rose swiftly. McGill soon appointed him to a full professorship. Osler also assumed the role of a pathologist in a smallpox hospital and practiced privately as well. For the next ten years, Osler was uncommonly productive professionally; he published extensively in the fields of clinical medicine, pathology, and veterinary medicine. At McGill, he worked to bring the medical school into a close relationship with the University. He also helped to develop modern methods of teaching physiology and performed over 1,000 autopsies to augment his research and educational aims.

In 1884, Osler left Montreal for Philadelphia, were he was appointed professor of clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. While at Penn, he continued his clinical investigations, spending many hours in the postmortem rooms performing autopsies. He maintained his earlier emphasis on superior patient care, conducting famous ward walks in Old Blockley, a unit of Philadelphia Hospital.

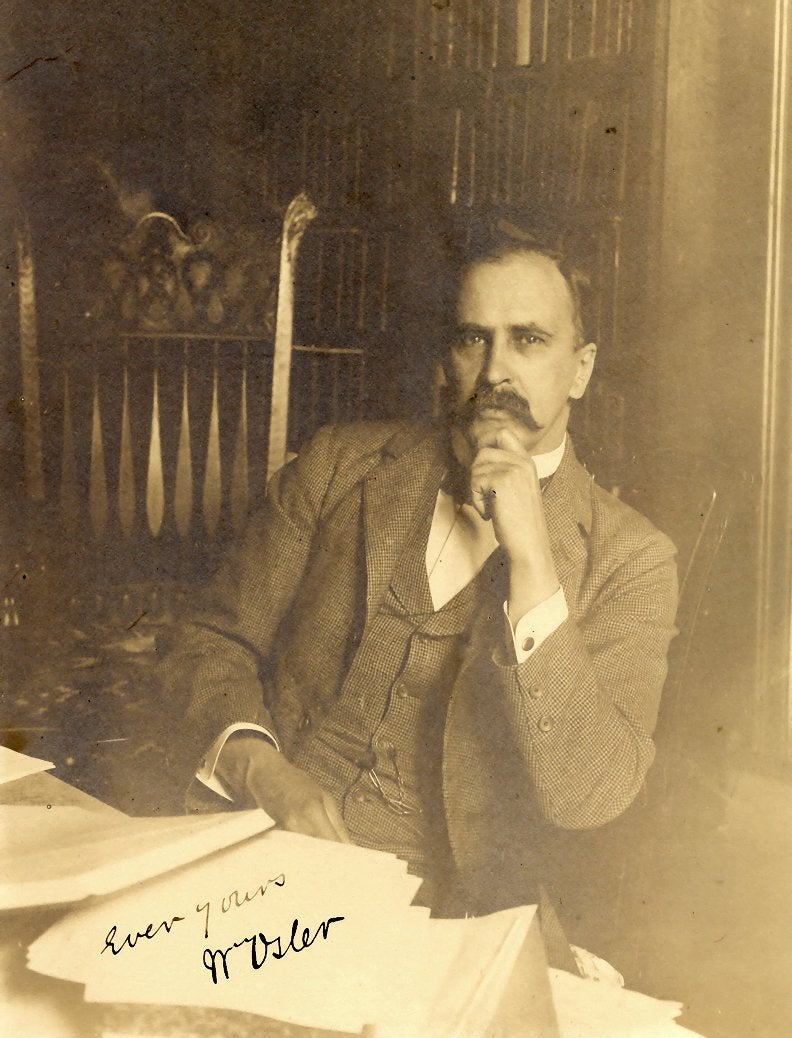

Osler’s tenure at Penn was brief. After only four years, he moved to Baltimore in the fall of 1888 and became the physician-in-chief of the recently organized Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler was one of the founding four members of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and played a decisive role in shaping the new medical school, which did not begin accepting students until four years after the inauguration of the Hospital. When the medical school finally opened, Osler became a professor of the principles and practice of medicine.

During his years at Hopkins, Osler made numerous outstanding contributions to the field. Perhaps most significant were his educational reforms, which extended beyond Hopkins into the international medical scene. His innovative teaching program for medical students and house staff was centered on instruction of small groups. The students served as clinical clerks on the wards and were responsible for detailed case histories and examinations.

With those innovations, Osler helped cast a new template for medical education in America. His emphasis on close and frequent contact with patients and a formalized program for postgraduate education would shape the standards of medical education for most of the twentieth century.

At the same time that Osler worked to develop new medical curricula, he turned his attention to an equally daunting task: the publication of a textbook of medicine. Osler’s work, first published in 1892 as The Principles and Practice of Medicine, filled a void in medical pedagogy. Up to that point, no modern text on internal medicine adequately discussed medical advances of the preceding fifty years. Osler’s textbook was immediately considered the standard text on clinical medicine; triennial editions were published throughout Osler’s lifetime without serious competition, and the work was translated into French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and Chinese. After Osler’s death, revisions continued to be published by others.

Osler’s textbook stood out in the field for its straightforward, jargon-free style and attention to historical context. The work also departed significantly from the prevailing design of previous textbooks of general medicine. Osler created a textbook with rigid format; he classified diseases according to pathogenesis or anatomical position. His design remained the standard pattern for American textbooks of internal medicine until 1950, when Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine reverted to general discussion of human biology rather than disease entities.

While at Hopkins, Osler’s interest in medical history grew manifest. He became fascinated by the genesis of the medical profession and encouraged a similar interest in his students. Osler helped to found a medical-historical society at Hopkins and later began to publish a series of historical essays that highlighted the lives and contributions of individual practitioners.

In 1904, Osler was offered the regius professorship of medicine at Oxford University, one of the most prestigious appointments in medicine, and a staff appointment at the Radcliffe Infirmary. The invitation, which was issued by King Edward VII, reflected the international scale of Osler’s reputation. He enthusiastically accepted the appointment and immediately assumed a decisive role in the Oxford medical community.

With no students to teach (Oxford medical students did their clinical work in London), Osler focused his attention on patients and postgraduate students. He continued to pursue reforms in clinical teaching and spent a great deal of time in the wards of Radcliffe Infirmary visiting patients. While at Oxford, Osler also expanded his literary and humanistic studies, devoting significant time to his endeavors as a bibliophile and medical historian. His own personal library, which he added to extensively during this period, would become one of the world’s great medical libraries.

Osler’s scientific contributions, while certainly substantial, were not as momentous as his reforms in clinical teaching. He was especially interested in cardiac diseases and endocarditis (inflammation of the lining of the heart). Osler also investigated typhoid fever, malaria, pneumonia, amebiasis, tuberculosis, and the relation of gallstones to the typhoid.

Until the end of his life, Osler’s literary output — both medical and historical — was prodigious; his published bibliography contains almost 1,500 entries. He was also in great demand as a speaker, which led to the publication of several of his addresses in Aequanimitas (1904) and An Alabama Student (1908). A series of his lectures given at Yale in 1913 were published posthumously in 1921 as The Evolution of Modern Medicine.

Osler died at his home in Norham Gardens, Oxford, on December 29, 1919, from pneumonia. Upon his death, his extensive personal library was bequeathed to McGill. The organization of the library was particularly notable; Osler categorized his books according to their perceived importance to the medical field or to their contribution in areas such as literature, medicine, biography, bibliography, incunabula, and manuscripts. In 1929, a decade after his death, the library published a catalog of the collection titled Bibliotheca Osleriana.

Osler’s name remains relevant in the medical field in several areas. In 1888, he observed tender subcutaneous nodes in subacutre bacterial endocarditis, now known as Osler’s nodes. Other eponyms include Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, or hereditary telangiectasia, and Osler-Vaquez disease, or polycythemia vera. He is still known as one of the most influential physicians in the English-speaking world.