On this page:

A complete list of College graduates, plus a partial list of non-graduates, can be compiled for the 18th century, but only some of the Academy students and hardly any of the Charity School students can be identified by name. Despite the anonymity of so many students, surviving documents do provide insight into what daily life was like on the campus.

During the eighteenth century, the Academy, Charity School and College were all housed on the same campus and governed by the same board of trustees. Each school had separate classrooms, but the students shared the same buildings, play yards, and sometimes even teachers. Older college students occasionally assisted in other schools. All schools shared a basic daily routine. Extra-curricular activities, even sports, consisted of only what the students could improvise.

The morning bell was wrung every day at either six or eight, depending on the season, and the evening bell a little before five. The students were to gather for roll call, and punctual attendance at these hours was considered necessary “to discourage Slothe & promote a manly Spirit of Industry.” Students who failed to come on time without a reasonable excuse were chastised, or incurred a penalty of two and a half pence.

What was the mix of College, Academy, and Charitable School students?

At any one time during the colonial and Revolutionary periods, about three hundred boys and ten teachers shared the classroom building and the dormitory of the Fourth Street Campus. Throughout the 18th century, college students were a minority on campus, clearly outnumbered by students in the Academy and Charity Schools.

The first graduating class of the College included a dozen students, eight of whom received their bachelor’s degrees. The largest graduating college or university class before Benjamin Franklin’s death was the Class of 1789 with 17 graduates; the largest graduating class in the 18th century was the Class of 1792 with 36 graduates. There were no graduating seniors in the years 1758, 1764, 1774, 1778, 1779, 1796 and 1798. Non-graduating members are not always documented, but it is apparent that many young men attended the college for a year or two, but did not stay to complete their degrees.

Classes at the Academy began on January 7, 1751, with only seventeen students. By 1756, the year after the opening of the College, there were 123 students in the Academy. By 1757, when eight of the twelve members of the first class received their A.B. degrees, the combined student body of the College and Academy numbered more than 180. The turnover of matriculates was high in the Academy, but when some scholars failed to return, new applicants replaced them.

The Charity School for boys opened in September 16, 1751; the girls’ branch of the Charity School opened in 1753. During the eighteenth century enrollment was as high as one hundred boys and forty or more girls. Until 1764, Charity School classes for both sexes were held in the same buildings used by the Academy and College. After 1764, the headmistresss and her charges were removed to another location in the city, but the Charity School for boys continued to share the Fourth Street campus with the College and Academy for the rest of the century.

Who were the students?

During the eighteenth century, students were attracted to the College and Academy of Philadelphia for many different reasons. Most liked its location in the heart of the colonies and the living accommodations of Philadelphia. Others came because of its non-sectarian control, its excellent curriculum, and the prominence of its professors.

The students who attended the College and Academy represented a variety of social, political and economic backgrounds. Their diversity created a healthy classroom atmosphere, which evidently provided them with democratic social exchange and encouraged the expression of their individual talents. The records of the College Class of 1757 and the classes that followed show that a large number of the students came from the homes of prominent trustees and faculty members. But others came from respectable, but less privileged backgrounds, often seeking training in the practical subjects of English, accounting, navigation and mechanics that would equip them for prompt and profitable employ; hence, most of these students ended their formal education in the Academy, rather than in the College. Children from the lower classes were also very much a presence on the campus; as students in the Charity School, they shared the same buildings with College and Academy students even though the Charity Schools’ curriculum was much more rudimentary.

Although the College and Academy attracted young men from many American colonies and even the West Indies, sixty percent of its matriculates for the first six years were drawn from Pennsylvania. Many others came from nearby Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey.

The age of students at the time of their matriculation into the Academy and College varied greatly. Boys seem to have been admitted to the Academy between the ages of seven and thirteen, and then placed in the proper class depending on the extent of their earlier training. Few people appeared to have entered the College before reaching age thirteen, but many received degrees at the age of sixteen or seventeen.

Did students live on campus?

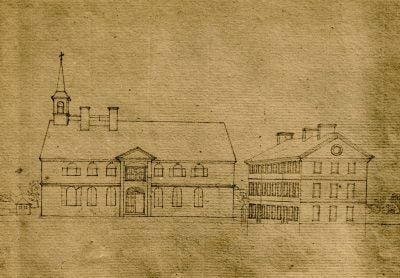

Many students in the Academy and College were Philadelphia natives and lived at home with their families. But for students coming from other parts of Pennsylvania or other colonies, the problem of student housing assumed greater importance. Before the construction of the dormitory, arrangements were made to place Academy and College students with relatives or guardians, in the homes of faculty, or in suitable boarding houses (such as the one run by widow Rachel Marks Graydon). In 1765, the campus was expanded by the opening of the newly completed dormitory, shown in this contemporary sketch by DuSimitiere.

Ebenezer Kinnersley, a professor, was made steward of this dormitory and given powers of discipline over the boys. In these duties, he had the assistance of his wife, who supervised the collection and washing of the students’ soiled clothes as well as their hygiene. However, even after its construction, the dormitory was never a popular abode with the students, many of whom sought living quarters elsewhere, where they would have more freedom. Since this resulted in considerable loss of funds to the College, in October of 1775, the trustees voted to lease the building to a private family who would board the pupils at a reasonable rate. In another attempt to control the off-campus activities of the scholars, the trustees agreed not to admit any out-of-town boy unless he was lodged in a place which they and the faculty considered proper.

Students who lived in the dormitory were never far from the view of their teachers. Not only did Ebenezer Kinnersley supervise the dormitory, other faculty also lived on campus. The Trustees owned three houses on Fourth Street, just north of the campus’s New Building; the largest residence was on the corner of Fourth and Arch Streets. The Trustees Minutes and a 1779 Plan of the College grounds show that, during the eighteenth century, faculty tenants included James Davidson, John Andrews, William Rogers, and John Ewing.

Was there any extracurricular life?

Students were left to their own devices when it came to amusements outside of the classroom. There were no organized student organizations or sports teams.

Although athletics was not a regular part of the curriculum of the Academy and College of Philadelphia and it would be over a century before Penn students had any organized, regular sporting events, athletic activities were not entirely absent from the lives of these early students. Benjamin Franklin himself was a swimmer, skater and an advocate of exercise and physical fitness for young men. Thus it is not surprising that at least one account of an athletic contest between students has survived.

This record of a Penn athletic event was penned by Alexander Graydon (1752-1818), who first enrolled in the Academy of Philadelphia as a young boy in 1760. After his father’s death the following year, Graydon’s mother moved from Bristol to Philadelphia where she took in boarders to help make ends meet. Her boarders included not only sophisticated theater people and British officers, but also students at the Academy and College, located nearby at Fourth and Arch Streets. Alexander Graydon, living with his mother, continued his studies at the Academy and College of Philadelphia until September of 1766, when at the age of fourteen he withdrew to study law in the office of his uncle.

In his memoirs, first published in 1811, Alexander Graydon described this race run by some of the students:

My mother… had taken a house in Arch Street, facing the Friends’ burying ground. The first lads that were place with her were two brothers, the sons of Colonel Lewis, of Virginia. The younger, named Samuel, had the attractions of a pleasing countenance and a great gentleness of manners… There was not a boy in school in whose welfare and competitions I took so decided an interest; the ardor of which was in almost perpetual requisition, from the circumstance of his being a champion in the gymnastic exercise of running, which was then the rage. The enthusiasm of the turf had pervaded the Academy, and the most extravagant transports of that theatre on the triumph of a favorite horse were not more zealous or impassioned then were acclamations which followed the victor in a foot-race around the square. Stripped to the shirt, and accoutred for the heat by a handkerchief bound round the head, another round the middle, with loosened knee-bands, without shoes, or with moccasins instead of them, the racers were started; and turning the left around the corner of Arch Street, they encompassed the square in which the Academy stands, while the most eager spectators, in imitation of those who scour across the course at a horse race, scampered over the church burying ground to Fifth Street, in order to see the state of the runners as they passed, and to ascertain which was likely to be foremost, on turning Market Street corner. The four sides of this square cannot be much less than three-quarters of a mile; wherefore, bottom in the coursers was no less essential than the swiftness, and in both Lewis bore away the palm from every one that dare enter against him. After having, in a great number of matches, completely triumphed over the Academy, other schools were resorted to for racers; but all in vain-Lewis was the eclipse that distanced every competitor, the swift-footed Achilles, against the vigorous agility of whose straight and well-proportioned form the long-legged stride of the overgrown and the nimble step of the dapper were equally unavailing.

What were the costs to students?

The Charity School was funded largely by donations and benefit entertainments. The Academy and College depended partly on donations and lotteries, but primarily on tuition and other fees collected from students and their sponsors. For most of the eighteenth century, tuition costs were four pounds per year. Later in the century, student fees included not just an admission fee, but also a charge for firewood.

In the early days of the Academy, pupils paid their tuition fees directly to their instructors. However, because many did not pay their tuition on time and some even left without settling their debts, the trustees were forced to order strict observance to the regulation of the tuition costs. Every student had to “get some Person of Reputation in Philadelphia to engage in writing the due payment of the Tuition Money.” This sponsor was usually the student’s father, a trustee, a friend or “a man of substance,” whose name immediately followed that of the student in the Account Book. To protect the institution from financial loss, the trustees decreed in 1766 that no student could be admitted into any of the schools without first producing a receipt showing payment of twenty shillings entrance money and without having his sponsor guarantee the cost of tuition and expenses.

– Minutes of the Trustees, January 21, 1766 and January 19, 1769