Charles Thomson was born the son of John Thomson in Maghera parish, County Londonderry, Ireland. After the death of his mother in 1739, Charles Thomson left for the American colonies with his father and two or three brothers. After the father died at sea, the sons landed in New Castle, Delaware. Here Charles was put in the hands of a local blacksmith. About 1743 Charles entered Francis Alison‘s New London Academy in nearby Chester County, Pennsylvania.

After several years of classical training, Charles Thomson was the first tutor hired by the Academy of Philadelphia (the forerunner of the University of Pennsylvania). He served as a Latin School tutor from 1750 until 1755, living for part of that time as a boarder in the home of English master David James Dove.

The trustees were evidently pleased with his work since he received a raise from the trustees in 1753. After several years he was given the additional duty of collecting outstanding subscriptions and keeping accounts of school money. When, in March of 1755, Thomson notified the trustees that he was leaving his position as Latin School tutor, the trustees noted that Thomson “had discharged the duties of his place with capacity, faithfulness and diligence.”

Thomson, a rationalistic rather than revivalistic Presbyterian, then became head of the Latin department at Philadelphia’s Friends’ Public School. In 1758 he married Ruth Mather, member of a well-to-do Chester family and sister of Joseph Mather, College Class of 1757. Soon thereafter, in 1760, Thomson left teaching altogether to enter business. His first venture, a dry goods business in Philadelphia, was not very successful. He and his first wife separated in 1769; the following year their infant twins and then Ruth herself died. In the early 1770s, Thomson was briefly engaged in the distilling of rum, and then as manager and part-owner of Batsto Ironworks in New Jersey.

A member of Benjamin Franklin‘s Junto (the origins of the American Philosophical Society) since the early 1750s, Thomson soon became involved in Philadelphia politics. In 1755, while at the Friends’ School, Thomson joined the Quakers in their opposition to the Penn family’s Indian policy. This was how he became secretary to the Delaware Indians when they met with proprietary officials in Easton in 1757 and 1758. During the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, Thomson moved away from Franklin to align himself with John Dickinson, working diligently throughout the Revolutionary period to keep English goods out of Philadelphia. By 1773 he was writing fiery handbills against the importation of tea from the East India Company. During this decade Thomson was the colony’s most powerful protest organizer.

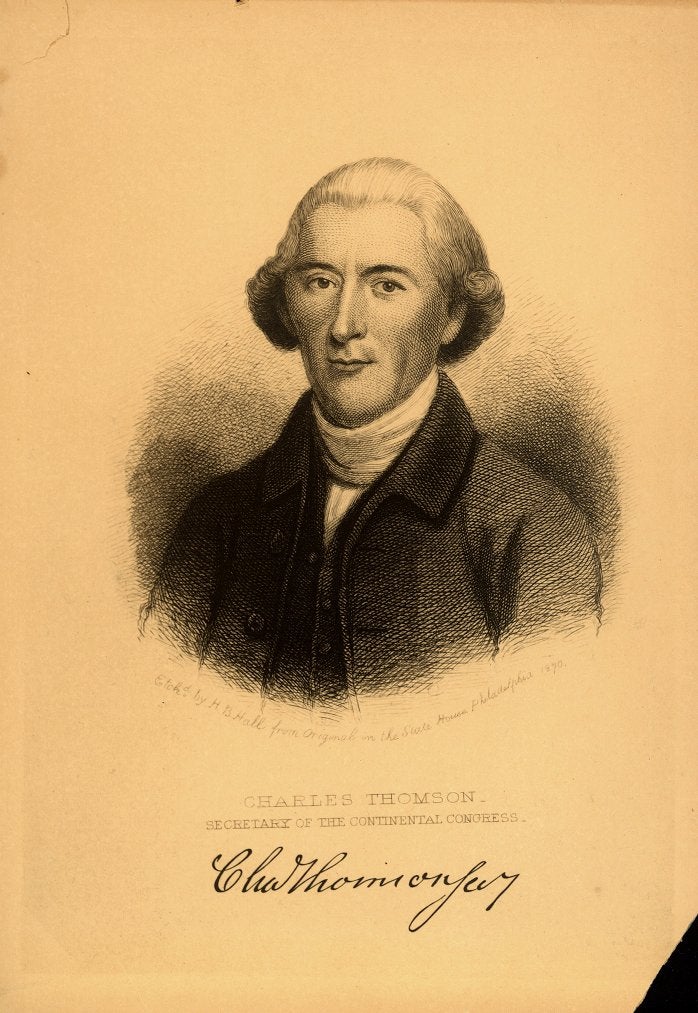

In September of 1774 Thomson immediately gained wealth, social position, and political office by his marriage to Hannah Harrison, daughter of wealthy Quaker Richard Harrison. Thomson was immediately chosen secretary of the Continental Congress at its first meeting, and served over the next fifteen years as secretary to the first and second Continental Congresses and then to the Confederation Congress. He also took an active role in foreign affairs. He strongly opposed Pennsylvania’s radical 1776 state constitution, instead backing Robert Morris. Thomson’s political stands, his pride and hunger for status, plus his role in Morris’ questionable financial dealings earned him many powerful enemies. He retired from public life at age fifty-nine to reside at Harriton, his wife’s estate near Philadelphia, where he occupied himself by translating the Greek Old and New Testaments.