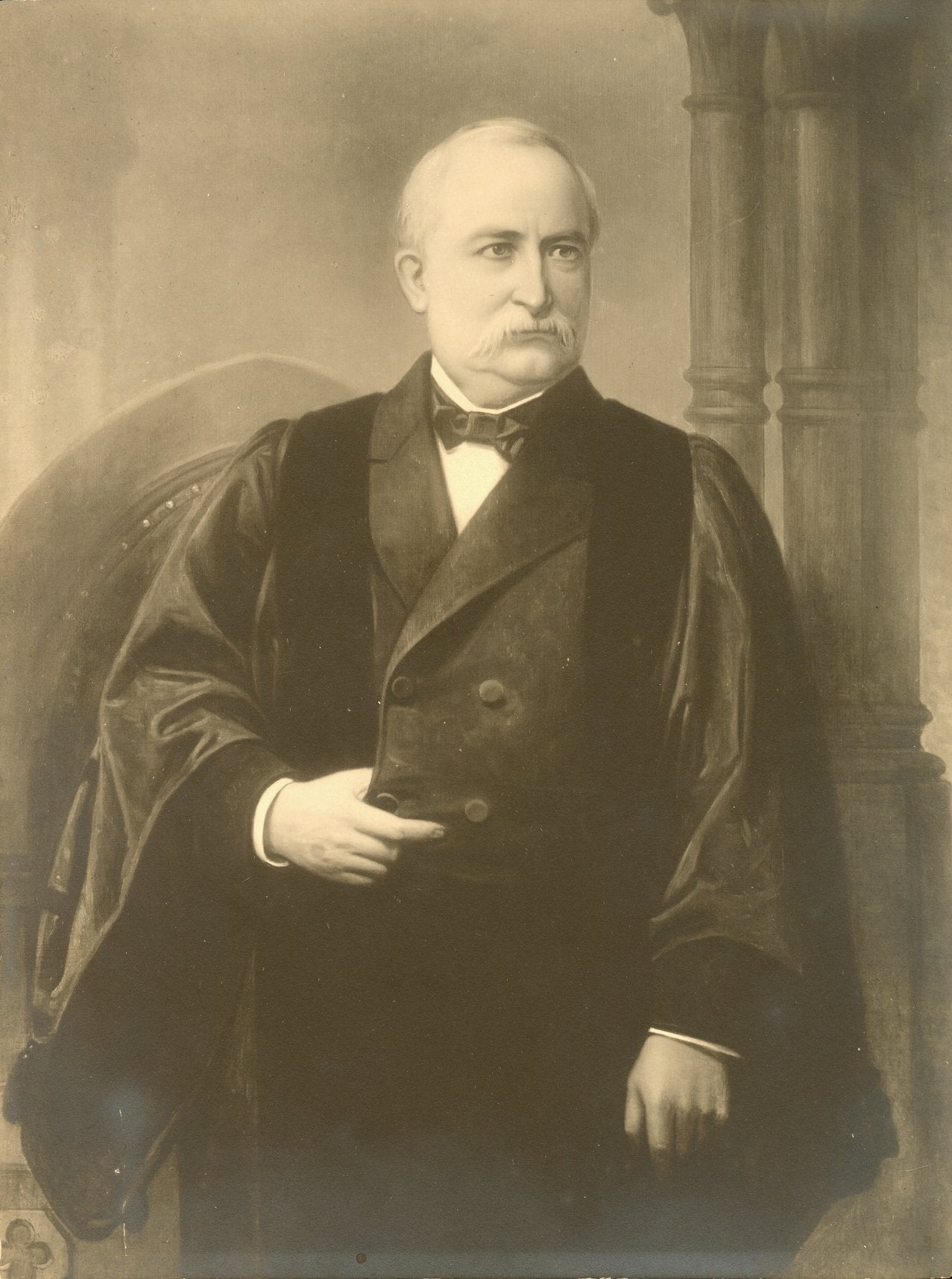

Charles Janeway Stillé, the tenth provost of the University of Pennsylvania, was born in Philadelphia in 1819. Stillé was a descendant of some of the first European colonists to settle in the Delaware Valley. During his youth he attended the school of the Reverend Dr. Steele in Abington, Pennsylvania, and the Edge Hill School near Princeton, New Jersey, before matriculating at Yale University. After he graduated with honors and as the valedictorian of the Class of 1839, Stillé began working in a law firm in Philadelphia and was admitted to the bar there in 1842.

Stillé’s life consisted of little of note until the 1860s. In the early 1860s, Stillé was named to the United States Sanitary Commission and wrote a history of that commission in 1866. During the American Civil War, Stillé wrote two pamphlets; the more famous of the two, How a Free People Conduct a Long War, was modeled off the British strategy for fighting against Napoleon in the early nineteenth century. How a Free People Conduct a Long War was so popular that about five hundred thousand copies of it were made during the Civil War.

After the Civil War ended and Stillé’s history of the Sanitary Commission had been published, he was hired as a professor of English literature and belles-lettres at the University of Pennsylvania. After Stillé argued that Penn institute elective courses of study, the University in 1867 instituted that very type of class. The following year he was named provost and received his first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws, on this occasion from his alma mater, Yale University.

Stillé’s career as provost was truly remarkable. During his twelve years in office the face and spirit of the University of Pennsylvania drastically changed. In 1872, Stillé moved Penn from its Ninth Street home to its current West Philadelphia campus and oversaw the opening of the Towne Scientific School. Two years later Stillé presided over the opening of University Hospital (later the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania). In 1877, he presided over the opening of the School of Music at Penn, followed in the next year by the School of Dentistry. Stillé was also successful in his attempts to allow women to attend certain lectures on campus, taking the first steps towards co-education at Penn.

Perhaps Stillé’s most important accomplishments as provost were the steps he took to place Penn on solid financial footing. In the eighty years before he took office, Penn had received exactly one financial donation amounting to a paltry $5,000. During Stillé’s twelve years in office he brought in about $2,000,000 in donations to the University of Pennsylvania, allowing for various academic chairs throughout the University, scholarships for women and graduates of Philadelphia public high schools, and for endowments for, among other things, the Towne Scientific School. The latter of these scholarships was extremely beneficial to Penn as it facilitated the beginning of a tighter bond between the City of Philadelphia and the University.

Aside from moving the University, adding schools, and ensuring its financial stability, Stillé wanted to revamp Penn’s power structure. Among other goals, he wanted the position of provost to become the chairman of the board of trustees. The board of trustees’ vehement opposition to Stillé’s plans eventually led to Stillé’s resignation in 1880.

After leaving the University of Pennsylvania, Stillé remained active as a writer and historian. He published Reminiscences of a Provost outlining his career as Penn’s provost and his disagreements with its board of trustees and served for a number of years as the president of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Although he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Penn in 1896, it appears as though Stillé never truly forgave the University for the cause of his resignation. In his will, Stillé left none of his considerable estate to Penn and a large portion to his alma mater, Yale. Stillé also left a large portion to his longtime wife. The couple had no children.