Wideman’s recounting of his Penn experience as a minority, mirrors that of other minorities at Penn at the time. Wideman’s intelligence and athleticism made his experience as a minority far easier, despite his frequent struggles. For instance, in late February of 1963, Stanley Baker Daniels, a junior in the College, was denied housing at the University approved Covington Apartments at 18 South 37th Street based on the color of his skin. According to the Daily Pennsylvanian article discussing the story, Daniels called the landlord at the Covington Apartments. Within moments of learning over the phone that there were vacancies at the apartments, Daniels inquired in person at the apartments. Upon reaching the door of the building, landlord William B. Tirpaeck, seeing that Baker was African American, claimed that the open apartments had miraculously been rented and that Baker was not allowed onto the premises.

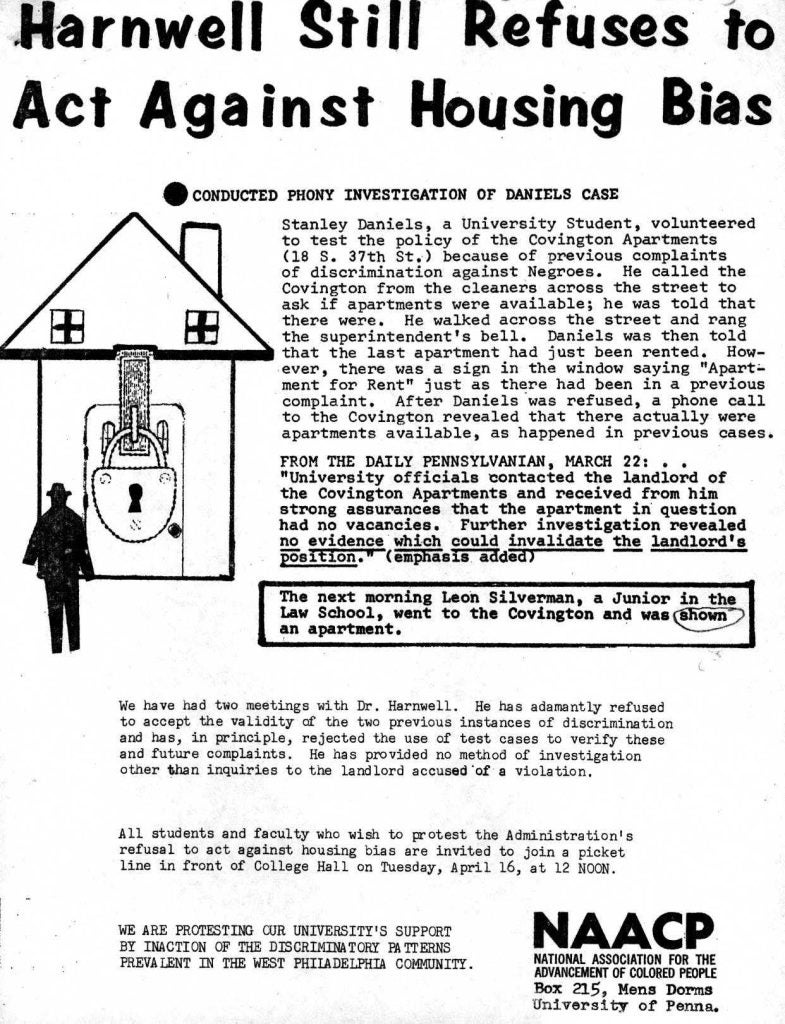

As a result of such blatant housing discrimination, Penn’s NAACP chapter protested outside of Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell’s office. According to Daily Pennsylvanian reporter James J. Lack, “The NAACP charges that the University, by refusing to do anything, is supporting the ‘discriminatory patterns in the West Philadelphia Community.'” Harnwell argued that the University would no longer approve a particular apartment building, if the University received a significant number of student complaints. The Presidents Office issued a statement in regards to the NAACP demands, explaining, “The University is proceeding actively in cases of alleged discrimination coming to its attention and will remove a property from the approved list where evidence of discrimination is conclusive.”

The NAACP responded by rebutting Harnwell’s policy about the insufficient number of complaints, stating, “The NAACP takes issue with this statement on the grounds that there are not enough Negroes enrolled in the University to provide a suitable amount of complaints in any given year.” In a flyer distributed around campus, the NAACP vehemently argued with the Harnwell administration, responding, “WE ARE PROTESTING OUR UNIVERSITY’S SUPPORT BY INACTION OF THE DISCRIMINATORY PATTERNS PREVALENT IN THE WEST PHILADELPHIA COMMUNITY.” In essence, University policy coupled with a staggeringly low African American student population allowed local institutions to discriminate blatantly against non-whites without violating University policy.

Harnwell, though, eventually solved the crisis by convincing Covington Apartments to integrate the building. In fact, basketball player Ed Anderson was one of two African Americans who would live in the Covington Apartments the following fall. “The University of Pennsylvania has a responsibility – and it also has a genuine desire – actively to support equality of opportunity,” Harnwell explained in a statement. Although Harnwell reacted slowly, his ultimate course of action indicated a concerted effort by the Penn administration to take calculated steps to prevent discrimination and ensure equality on campus.