It is unclear whether Wideman was the first African American basketball player at Penn. No African American appears in any basketball team photos in the Record from 1894 until Wideman’s sophomore year in 1961. In terms of his own class, Wideman specifically mentions in Brothers and Keepers that his freshman class in 1959 had roughly ten African American students out of a class of out of about seventeen hundred. When he met fellow senior classmate and African American Darryl Alexander Dawson he had met, in his own words, “approximately one-third of the total number of black males” in his class. The class of 1963 freshman directory photo head shots indicate that four other African American students matriculated to Penn with Wideman and Dawson in 1959, not far from what Wideman had speculated.

While Wideman and Dawson earned Bachelor of Arts Degrees in 1963, out of the five, only one other African American Male, Ronald Hines, received a degree. Stanley Baker Daniels spent two years working towards a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering followed by one year studying in the College of Arts and Sciences before leaving Penn without a degree.1 Morris A. Leaphart, who grew up minutes away from Penn’s campus in West Philadelphia, left school after just one year.

In 1960 and 1961 the number of African Americans matriculating at Penn remained relatively constant. Of the combined eleven African Americans in the graduating classes of 1964 and 1965, eight received degrees. Of these eight degree recipients, one graduated with distinction, William W. Sales Jr. and two others, Henry P. Cheatham III and Russell Hewett, went on to receive Masters degrees in Business Administration from the Wharton School. In spite of the small number of African Americans, those that attended and stayed at Penn were quite successful.Even though almost one third of African American males in the classes of 1963, 1964 and 1965 did not graduate, those that did receive degrees, excelled beyond expectations. For Wideman and Anderson in particular, their time at Penn prepared them admirably for life after college. Both Wideman and Anderson, in fact, returned to Penn after their college years, Wideman as a Professor and Anderson as a University Trustee. Wideman taught at Penn for six years, starting in September of 1967. In 1971, President Martin Meyerson appointed Wideman to direct Penn’s new Afro-American Studies Program. After attending Penn Medical School, Ed Anderson interned at Stanford University and eventually became the attending cardiologist at a large San Francisco Bay Area hospital.2 Anderson became a University Trustee in 1992 and has served the University for over ten years.

The success of African American students was not limited to just basketball players. 1964 College graduate William W. Sales Jr. later received a Ph.D. from Columbia University and currently chairs the Seton Hall University African American Studies Department. In 1994, he authored From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American, a comprehensive analysis of Malcolm X and the fight for African American unity.

Despite the wide ranging success of Sales, Wideman, Anderson and others, both during and after their time at Penn, African American students still experienced issues adjusting to the majority white student population. Wideman, for instance, recounts being interrogated about the Blues by a white peer to the point that Wideman nearly turned violent. As described by Wideman, the white classmate was “…trespassing on the private turf of my music, the black sounds from home I carry…His whiteness, his arrogance made me mad…I didn’t hit him. I should have but never did….” With his race under represented at an astonishing rate, Wideman had to consequently deal with personal isolation, confusion and anger.

Nearly twenty three years after leading Penn to the city championship, Wideman returned to Philadelphia to deliver the Baccalaureate speech for the 1986 commencement, revealing similarly despairing details about his first year on campus. As transcribed by the Pennsylvania Gazette, Penn’s monthly alumni magazine, Wideman told how he attended a mixer between Penn and about three hundred girls from Bryn Mawr. At the event, a couple of Wideman’s teammates (he does not give specific names) confronted him and told him that his tie was too long. So Wideman simply fixed his tie to a more conforming length. Reflecting on the experience, however, revived troubling thoughts for Wideman, as he pleaded,No big thing…But: put yourself in my shoes. Make this kind of adjustment – of tie, of shoes, of the way you say your name, of the rhythm in your speech, of the way you walk; do that a thousand times a day, and you begin to ask questions, like: Why shouldn’t I wear my tie the way I want to? What is tied up here? Why am I here?…And why are other people telling me these things?…

…Imagine yourself different. Imagine yourself different.

Despite his remarkable success, Wideman could never really be himself at Penn.

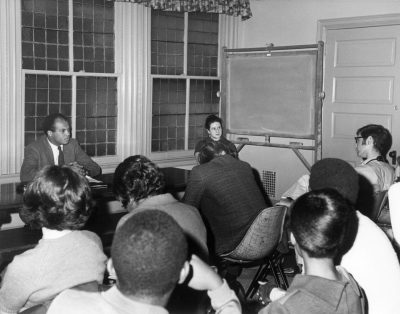

Wideman continued in his Baccalaureate address to explain that during his sophomore year, he realized there was an African American professor that worked at Penn. “Now that in and of itself – the fact that it took me a year to find that out and the fact that there was at that time only one – is a story,” Wideman exclaimed during his Baccalaureate speech. Wideman, however, would never meet this professor, whose name he would later learn was Dr. William Thomas Valeria Fontaine, the first African American to teach full time and receive tenure at the University. In response to why Wideman never interacted with Fontaine, he answers,Because if Bill Fontaine was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, he must be a special case. He probably wasn’t as good as the white professors. And so certainly, if I wanted to do my best, I wouldn’t ally myself with a Bill Fontaine. That’s the sort of self-delusion that I was laboring under. I had been told enough times that black was inferior that I had lost my capacity to image what black could be…I was afraid that what other people had told me about who I was, was in fact true; and if it were true about me, then it would be true about this man, this teacher. And I denied myself the possibility of opening up and growing at that time.

As a minority on Penn’s campus, Wideman was forced to question the abilities of his own race.

1. Daniels was involved in a housing discrimination controversy in the winter of 1963 which is discussed in more detail later. While there is no specific evidence that indicates he left school or did not graduate as a result of this, it is certainly possible that the incident played a role in his failure to receive a degree.

2. In 1999, Anderson consulted one time Ivy League opponent Bill Bradley regarding a heart condition. Campaigning in the Bay Area during his campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination, Bradley visited Anderson, who assured him and the rest of the nation that Bradley was healthy and fit for the presidency.