As a Rhodes Scholar, Wideman was heralded in the national media. Look magazine’s article, “The Astonishing John Wideman,” by Gene Shalit, introduced Wideman to the nation, providing a stylized version of his Penn experience, focusing on how he overcame simple racial differences to succeed. Even though Shalit and others from Look followed the team on a road trip to Yale and Brown and attended Wideman’s classes, the article fails to discuss racial issues concretely, instead relying on trite and broad remarks about Wideman’s struggles, ignoring details or specific anecdotes. Shalit explained, “Girls call him up for dates, professors invite him to their homes for dinner…[T]he world is his plaything…Obviously it is not. John Wideman is a Negro….”

While the article alludes to Wideman’s struggles in the white Penn community, the general consensus of the article indicates that Wideman eventually worked his way around any racial problems. As a result of Shalit’s portrayal, the article provided the nation with a misleading perception of Wideman’s campus life. Look quoted Wideman as saying, “‘I used to feel relaxed with Negroes, but now I feel the same with white friends.” While not necessarily false, without providing more detail, the magazine does not reveal the entire story behind Wideman’s friends.

In an article in the Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin Magazine, Wideman himself reflected about his friendships at Penn, elaborating,

My circle of friends was restricted by circumstance rather than choice. Having much in common with people is a good beginning for friendship, good enough so that many external differences as race and religion are overlooked…The danger of the college experience is that it tends to make one forget. After playing ball, socializing, living with men as equals during four years, it is natural to project this ideal situation as the rule and not the exception.

Unlike the magnanimous friendships portrayed by Look, only common experience allowed Wideman to meet white friends.

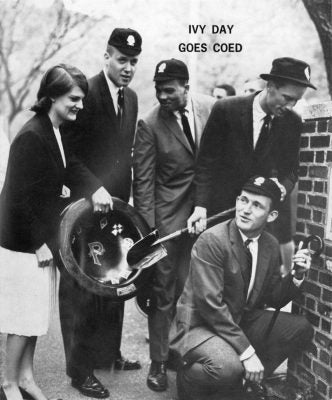

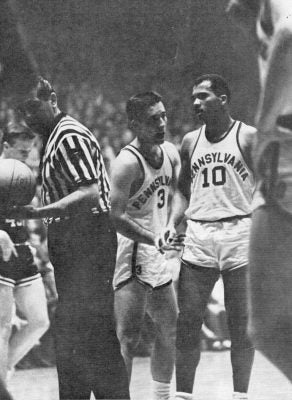

Nonetheless, Wideman did in fact form a strong bond with his teammates due to circumstance, regardless of race. During the 1963 season Wideman roomed with three fellow seniors, Dave Robinson, J.D. Graham and Bob Purdy. The quartet would often throw parties in their off campus apartment. Despite Wideman’s national acclaim during the ’63 season, his teammates appeared incredibly congratulatory and seldom jealous. After Wideman won the Rhodes Scholarship, his teammates jokingly provided him with a British umbrella and a bowler hat to prepare him for his stay in London. Even though he developed a bond with his teammates, he still never felt comfortable, as these were his friends that could not understand why he would wear such a long tie or who, in Wideman’s opinion, owned far too many undershirts.While Wideman’s struggles to find his identity and feel comfortable at Penn could have been an isolated case, he himself indicated that his difficulties were not unique. Despite the small number of African Americans on campus, people nonetheless criticized minorities that appeared to have come to Penn on athletic merit only, according to Wideman. Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson analyzed what Wideman dubbed “the hypercritical atmosphere” at Penn. Dolson quoted Wideman as saying, “‘We have people (undergraduates) here who want to go out to a game to laugh and have a good time…Then the team starts winning and those people say, ‘You’re importing animals to play.'” While Wideman’s comments may not be specific to race, he sends a clear message that, regardless of success, those who were perceived as outsiders were still conspicuous and not openly accepted on Penn’s campus.