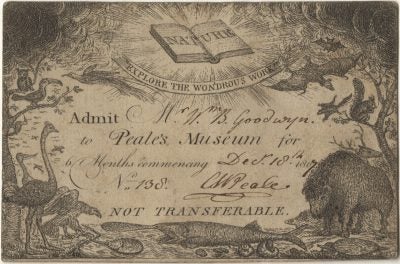

42. Peale’s Museum

| Peale’s Museum 1807 Peale, Charles W. Goodwyne, Wm. B. Museum privileges |

|

| Philadelphia intellectual institutions augmented the education of University of Pennsylvania medical students in the school’s early years. Peale’s Museum, created by the renowned artist and naturalist Charles Wilson Peale, was one such place where medical students could learn from the museum’s extensive specimen collection. Peale served as one of three co-curators of the American Philosophical Society from 1788 to 1811. In this capacity he worked with several Penn faculty including Benjamin Smith Barton, professor of materia medica, natural history and botany (69). In tandem with Barton’s course on natural history, Penn medical student Goodwyne (M1809) of Virginia had an admission ticket to Peale’s Museum, signed by Peale. The museum attracted many subscribers from the medical profession: physicians, medical students and dentists.

Brigham, David R. Public Culture in the Early Republic. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995. 18, 94-95.

|

|

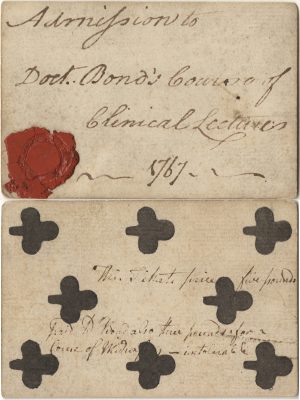

43. Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System)

| Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System) 1767 Bond, Thomas, MD Armstrong, James Clinical lectures |

|

| Although Armstrong’s name does not appear on the handwritten ticket, it is attributed to him because it was donated to the University of Pennsylvania Archives with Armstrong’s other tickets. It is an example of the adaptation of ordinary playing cards for use as medical lecture tickets. On the back, Armstrong wrote, “This ticket price of five pounds paid Dr. Bond also three pounds for a course of Midwifery — intolerable.” Armstrong may have been disgruntled because he had expected that the original charge of five pounds was to have covered all subjects. In 1766 Bond, a physician, surgeon and founder of Pennsylvania Hospital (1751), taught the first course of clinical lectures in the United States to the first students attending Penn’s new medical school. Although Bond never officially held a Penn professorship, he taught medical students at the hospital until his death in 1784.

Corner, George W. Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Phila: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965. 24-25.

“Historical Matriculation Cards: Governor Pennypacker Finds Treasures for the University.” Old Penn. Vol. IV, No. 25. March 17, 1906. University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Penn Biographies. Thomas Bond. |

|

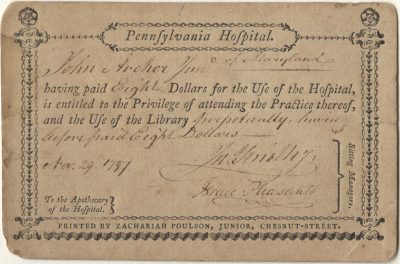

44. Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System)

| Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System) 1797 Smith, James, Jr. and Pleasants, Israel (sitting managers) Archer, John Jr. Hospital and library privileges |

|

|

From the time Pennsylvania Hospital was founded in 1751, attending physicians exposed their apprentices to medical and surgical practices. When the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) started its medical school in 1765 with lectures on materia medica and anatomy, Pennsylvania Hospital provided a venue and faculty for clinical lectures. John Archer, Jr. (Penn; M1798) of Maryland was the son of John Archer, who in 1769 received the first Penn medical degree ever awarded thanks to an alphabetical advantage.

Morton, Thomas G., MD. The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751-1895. Phila: Times Printing House, 1897.

|

|

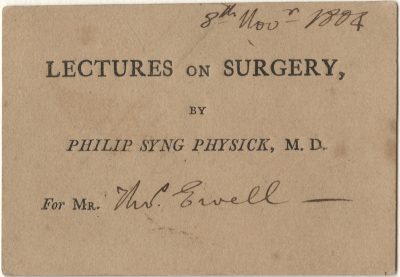

45. Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System)

|

Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System) 1804 Physick, Philip Syng, MD Ewell, Thomas Surgery |

|

| Physick apprenticed with Adam Kuhn, MD (11) and took courses at Penn’s medical school, but received his medical degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1792. He returned to Philadelphia just in time to help Rush (12), Wistar (13) and others combat the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic. A year later he received an appointment as surgeon at Pennsylvania Hospital and at the request of medical students, lectured on surgery. The year following the subject lecture ticket, Penn elected him professor of surgery. Physick’s many practical innovations, including absorbable sutures, tonsillectomy instruments, a procedure for enucleating the lens from the eye and lithotomy, earned him the title, “father of American surgery.” His most famous case entailed the removal of more than 1,000 bladder stones from Chief Justice Marshall. While serving as a Navy surgeon from 1805 to 1813, Ewell (Penn; M1805) of Virginia became an expert in gunpowder manufacturing and developed techniques to improve its efficiency and safety. He also brought his chemistry background to bear in his Plain Discourse on the Laws or Properties of Matter Containing the Elements or Principles of Modern Chemistry (1806), a treatise of useful chemical knowledge for farmers, artisan and others nontechnical audiences.

Corner, George W. Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Phila: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965. 52.

Edwards, George. “Philip Syng Physick, 1768-1837.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1940 January; 33(3): 145-148. Goldsmith, Robert H. Old Chemistries: Thomas Ewell’s ‘Plain Discourses on the Laws or Properties of Matter.’ Bull. Hist. Chem. 9 (1991). 22-24. University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Penn Biographies, Philip Syng Physick (1768-1837). |

|

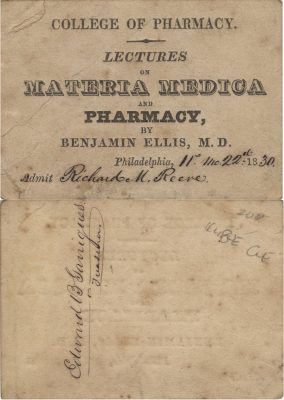

46. Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (University of the Sciences)

| Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (University of the Sciences) 1830 Ellis, Benjamin, MD Reeve, Richard M. Materia medica and pharmacy |

|

|

In 1821 the Philadelphia College of Apothecaries was founded, the first college of pharmacy on the American continent. The city’s apothecaries and druggists organized the College in response to the University of Pennsylvania’s proposal to create a masters program in pharmacy. Soon known as the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, the school offered lectures on materia medica and pharmacy, and on pharmaceutical and general chemistry. Like the medical schools, College of Pharmacy students purchased tickets to attend lectures and those fees went to the professors; however, the Trustees rather than professors fixed the price of tickets. Ellis (Penn; M1822) served as physician of the Philadelphia Dispensary and authored The Medical Formulary, of which at least 12 editions were published. He founded and co-edited the Journal of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. The College of Pharmacy appointed him Professor of Materia Medica and Pharmacy in 1827, four years before scarlet fever took his life at age 32.

England, Joseph W., editor. The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1821-1921. Phila: Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, 1922.

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 358-59. |

|

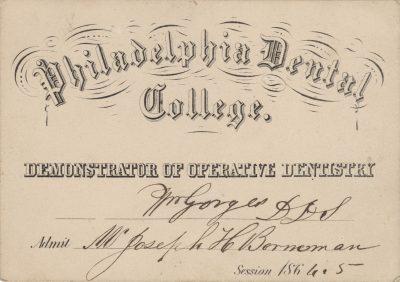

47. Philadelphia Dental College (Kornberg School of Dentistry, Temple University)

| Philadelphia Dental College (Kornberg School of Dentistry, Temple University) 1864-65 Gorges, William, DDS Borneman, Joseph H. Operative dentistry |

|

| At the time the Philadelphia Dental College was founded in 1863, most dental education consisted of private apprenticeships: only 13 dental schools in the US were established by 1868 and several of those were short-lived. Proprietary dental schools faced similar pitfalls in training qualified practitioners as did medical schools. The Philadelphia Dental College became part of Temple University in 1907. Similar to the 1910 Flexner Report that assessed medical education, the Carnegie Foundation sponsored a study of dental education in the 1920s. This study, “The Gies Report,” led to reforms at Temple, including requirements for pre-dental college instruction, a four-year curriculum and better facilities. Gorges joined the original faculty of Philadelphia Dental College as demonstrator of mechanical dentistry and taught operative dentistry one year later. Borneman, one of the early graduates, practiced dentistry in Boyertown, PA, for 25 years before entering the drugstore business.

Daily Pottstown Ledger, July 6, 1908.

Gies, William J. Dental Education in the United States and Canada. NY: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1926. Scharf, John Thomas. History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884. Vol. 2. Phila: L.H. Everts & Co. 194. |

|

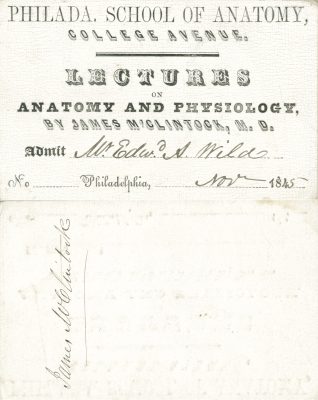

48. Philadelphia School of Anatomy (merged into Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine)

| Philadelphia School of Anatomy (merged into Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine) 1845 McClintock, James, MD Wild, Edward Augustus Anatomy and physiology |

|

|

McClintock (Jefferson; M1829) founded the Philadelphia School of Anatomy in 1838 to provide supplemental training to the city’s medical students, apprentices and practicing physicians. He located the school on College Avenue, behind the University of Pennsylvania’s 9th Street campus. The school provided instruction in all branches of medicine, but did not grant degrees. In 1847 McClintock merged the school into the Philadelphia College of Medicine, becoming dean and professor of surgery. Jonathan Allen, MD headed a successor “Philadelphia School of Anatomy.” D. Hayes Agnew, MD (93) acquired the school in 1852 and soon added Operative Surgery to the masthead and curriculum. Under Agnew’s 10 years of leadership, attendance reached 267 students at a time. Several proprietors followed Agnew until 1889 when the school became the Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine, which in 1916 became part of Penn’s Graduate Hospital. Wild was a student at Jefferson Medical College while studying here and at the Philadelphia Surgical Study (49). (For more on Wild, see 23.)

Billings, John S., MD. “The History and Literature of Surgery” in System of Surgery, Vol. 1., edited by Frederic S. Dennis, MD. Phila: Lea Brothers & Co., 1895. 140.

Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 103. |

|

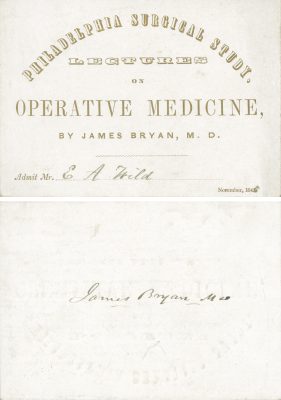

49. Philadelphia Surgical Study

| Philadelphia Surgical Study 1845 Bryan, James, MD Wild, Edward Augustus Operative medicine |

|

| Bryan (Penn; M1834) likely established the Philadelphia Surgical Study around the same time as McClintock’s Philadelphia School of Anatomy, and also within close proximity to the University of Pennsylvania. The school offered supplementary lectures and demonstrations on theoretical and practical surgery, and disease of the eye and ear. Surgical procedures were practiced on cadavers; the Philadelphia Dispensary provided opportunities to observe and treat patients. Bryan also taught institutes of medicine and medical jurisprudence and later surgery at the short-lived (1847-1859) Philadelphia College of Medicine. (For more on Wild, see 23 and 48.)

Chase, Heber. The Medical Student’s Guide: Being a Compendious View of the Collegiate and Clinical Medical Schools, the Courses of Private Lectures, the Hospitals and Almshouses, and Other Institutions which Contribute Directly or Indirectly to the Great Medical School of Philadelphia; With the Regulations of Hours, Fees, &c. and Other Information of Importance to Students. Phila: J.G. Auner, 1842. 31.

Early Pennsylvania Medical College Lecture Cards. http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Medical_Lecture_Tickets/Medical_college_lecture_tickets_7.htm |

|

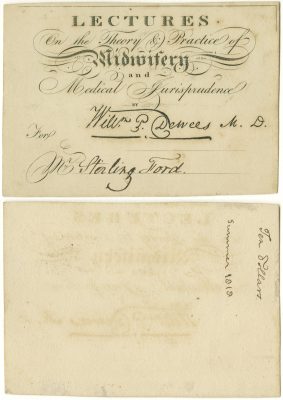

50. Private

| Private 1818 Dewees, William P., MD Ford, Stirling Midwifery and medical jurisprudence |

|

| Dewees (Penn; M1806), who practiced medicine after receiving his MB degree from Penn in 1789, offered the first full course on obstetrics in America. It was a private course on a subject slowly transitioning from the realm of midwives to physicians. It became its own course within the University’s medical curriculum in 1810, but Penn selected Thomas Chalkley James, MD (70) its first professor of midwifery. Disappointed, Dewees stepped away from medicine for a few years of farming, but in 1817 resumed his practice and private summer course and lectured at the new Medical Institute of Philadelphia (36). In 1825 Penn appointed Dewees adjunct professor of midwifery and in 1834, chair of midwifery. Among his significant contributions to medical literature, the most notable for obstetrics was his Comprehensive System of Midwifery (1824). On the back of this lecture ticket Dewees wrote, “Ten Dollars, Summer 1818.” (For Ford, see 3.)

Hodge, Hugh L. An Eulogium on William P. Dewees, M.D. Delivered before the Medical Students of the University of Pennsylvania, November 5, 1842. Phila: Merrihew & Thompson, Printers,1842

|

|

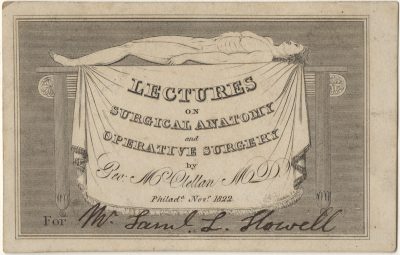

51. Private

| Private 1822 McClellan, George, MD Howell, Samuel L. Surgical anatomy and operative surgery |

|

| While a medical student, McClellan (Penn; M1819) worked as resident undergraduate in the Philadelphia Almshouse (3), where he spent a great deal of time practicing operations in the autopsy room. Degree in hand, he opened a dissecting room in 1820 and taught Penn medical students private courses on surgical anatomy and operative surgery, as well as anatomy and physiology. In 1824 he helped found Jefferson Medical College, which soon rivaled his alma mater. McClellan taught surgery there until the board of trustees replaced the entire faculty in 1838. He then founded Philadelphia’s third medical school, The Medical Department of Pennsylvania College, which operated from 1839 to 1861. Howell (Penn; M1824), a practicing physician and surgeon in Princeton, NJ, was professor of anatomy and physiology at the College of New Jersey. His untimely death in 1836 ended plans to establish a summer course of instruction for medical students at the College.

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 728-30.

Maclean, John. History of the College of New Jersey, from Its Origins in 1746 to the Commencement of 1854. Vol. 1. Phila: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1877. 300. Morton, Samuel George, MD. Biographical Notice of the Late George McClellan MD. Phila: William F. Geddes, 1849. |

|

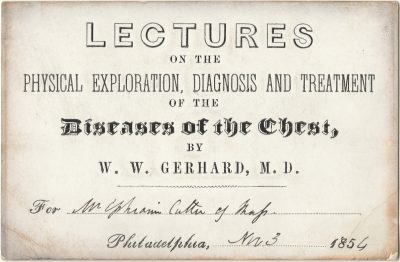

52. Private

| Private 1854 Gerhard, W.W., MD Cutter, Ephraim Diseases of the chest |

|

| After two years of postgraduate education in Paris studying diagnosis and pathology, Gerhard (Penn; M1830) brought new ideas about medical science to Philadelphia. He published an important paper distinguishing typhus from typhoid fever and the first accurate study of tubercular meningitis in children. Gerhard lectured on diseases of the heart and lung privately and at Philadelphia Hospital (3). In 1838 Penn appointed him assistant professor of the institutes of medicine, and when the University established a dispensary in 1841, it chose Gerhard and one other physician to run it. Cutter (Harvard; M1856, Penn; M1857) attended Gerhard’s private course while at Penn. He became one of America’s early laryngologists, invented many instruments including Cutter’s Stem Pessary for the treatment of fibroids, investigated early tooth decay in children, authored a book on cancer and diet, ran a private “School of Micrology “ and was a pioneer in microphotography. Cutter practiced in Massachusetts and later New York.

Br Med J. 1917 June 16; 1(2946): 827.

Corner, George W. Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Phila: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965. 91-92. Cutter, Ephraim, MD, LL.D., and John Ashburton Cutter, B.Sc., MD. Fatty Ills and their Masquerades. NY: 1898. Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 432-43. Mandabach, Mark G., MD and Amos J. Wright, M.L.S. “Dr. Ephraim Cutter, Early Laryngoscopist and Influential Physician of the 1800’s.” American Society of Anesthesiologists. |

|

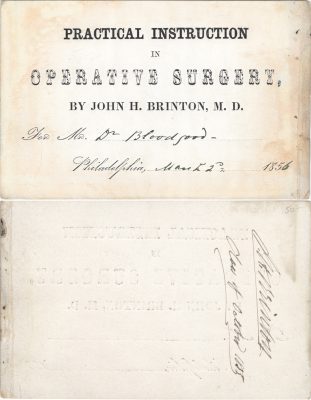

53. Private

| Private 1856 Brinton, John H., MD Bloodgood, Delavan Operative surgery |

|

| The back of this ticket, signed by Brinton (Jefferson; M1852), reads “Class of October 1855.” Brinton received his medical degree at age 20, pursued postgraduate study in Paris and Vienna, and from 1853 to 1861 maintained a private practice and lectured privately, as he did for Bloodgood, at the Philadelphia School of Anatomy (48), and for “Summer Association,” which offered all area medical students instruction between sessions. During the Civil War Brinton participated in several campaigns before being chosen to establish the Army Medical Museum and serve as its first curator. He also collected statistics for the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion and served as personal physician to General Ulysses S. Grant. He returned to Jefferson after the war for a long teaching career, succeeding Samuel Gross, MD as professor of the practice of surgery and clinical surgery, 1882-1906. Bloodgood (32) took Brinton’s course after receiving his degree from Jefferson in 1854 and before starting his career as a Navy surgeon in 1857.

Brinton, John H. (John Hill), 1832-1907. Papers, 1853-1896. http://cpparchives.org/repositories/2/resources/61

Civil War Surgery Manuals. Thomas Jefferson University Archives and Special Collections. http://jeffline.jefferson.edu/SML/Archives/Highlights/Manual/ John Hill Brinton Papers, MS 13. Thomas Jefferson University, Archives & Special Collections. “Part I: Jefferson Medical College 1846 to 1854 (pages 55-88)” (1992). Thomas Jefferson University – A Chronological History and Alumni Directory, 1824 – 1990, edited by Frederick B. Wagner, Jr., MD, and J. Woodrow Savacool, MD, 1992. Paper 16. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/wagner1/16 |

|