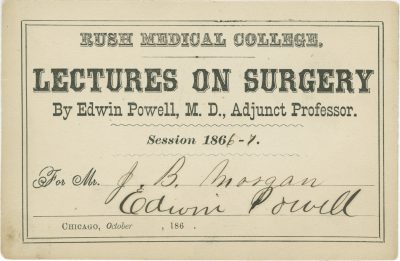

54. Rush Medical College (Rush University Medical Center)

| Rush Medical College (Rush University Medical Center) 1866-67 Powell, Edwin, MD Morgan, J.B. Surgery |

|

| Daniel Brainard, MD founded Rush Medical College in 1837 and named it in honor of the renowned Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, MD (12). It was Chicago’s first medical school and one of the earliest in the Midwest. The medical school affiliated with the University of Chicago from 1898 to 1941, closed its doors in 1942 and reopened them in 1969 in a merger with Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Hospital. Brainard’s nephew Powell (Rush; M1853) joined the Rush faculty as demonstrator in anatomy by 1859, and from 1863 to 1877 held the professorship of military surgery and surgical anatomy.

Rush University Medical Center. http://www.rush.edu/rumc/page-1134773754867.html

Thirteenth Annual Announcement of Rush Medical College, 1872-73. Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1872. |

|

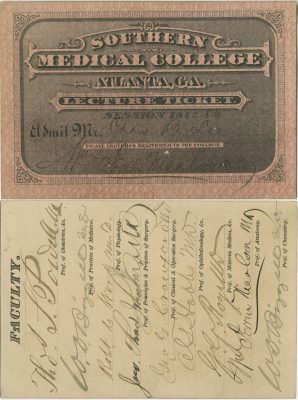

55. Southern Medical College (Emory University School of Medicine)

|

Southern Medical College (Emory University School of Medicine) 1882-83 Nicolson, Wm Perrin, MD (dean) Lee, Charles B. General lecture ticket |

|

| In 1878 a faculty fist fight about fixing up an old building broke out at the ante-bellum Atlanta Medical College. The confrontation led some professors to resign and start a rival school, Southern Medical College. In 1898 the two merged to form the Atlanta College of Physicians and Surgeons. Yet another disagreement seven years later resulted in the Atlanta School of Medicine. When the 1910 Flexner Report recommended that proprietary medical schools affiliate with universities to raise their standards, the two merged and in 1915 became Emory University School of Medicine. Nicolson (Medical College of Virginia; M1877) specialized in surgery and became professor of anatomy and lecturer on clinical surgery at Southern Medical College, and by 1882, dean of the institution. Other faculty listed on the back of the ticket are: Drs. Thomas S. Powell, William D. Bizzell, Robert C. Word, John Thadeus Johnson, George G. Crawford, Arthur G. Hobbs and Gustavus G. Roy.

Emory History: Places & Schools. http://emoryhistory.emory.edu/facts-figures/places/index.html

Heritage of the Georgia Surgical Society. Sholes’ Atlanta City Directory, 1882. Atlanta: H.H. Dickson, 1882. http://archive.org/stream/acpl_citydirectories_03_reel03#page/n5/mode/2up |

|

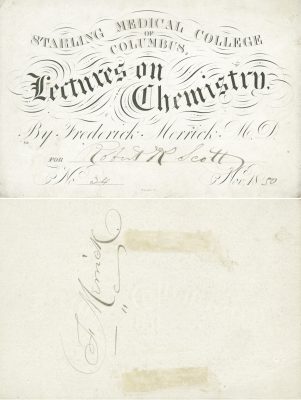

56. Starling Medical College of Columbus (Ohio State University College of Medicine)

| Starling Medical College of Columbus (Ohio State University College of Medicine) 1850 Merrick, Frederick, MD [sic] Scott, Robert R. Chemistry |

|

| Chartered in 1848, Starling Medical College replaced Willoughby Medical College, which recently had relocated to Columbus. Merrick, one of Starling’s first seven faculty members, was not an MD, but rather a Methodist minister charged with fundraising to found Ohio Wesleyan University. In 1845 he started teaching botany (and later chemistry) at the University; he simultaneously lectured on chemistry at Starling. Merrick served as Ohio Wesleyan’s second president. It remains unclear if his pupil, Scott, ever earned a medical degree. In 1850 he followed the Gold Rush to California to prospect and practice medicine. After the former venture failed, he returned to Ohio via Latin America and briefly established a medical practice. During the Civil War Scott rose to Major General in the US Army, and afterward served two terms as governor of South Carolina (1868-72), nearly facing impeachment for fraudulent financial practice. Scott returned to Ohio 1877. In a confrontation with his son’s friend, Scott’s pistol mysteriously fired and killed him. He pled guilty to accidental homicide and was acquitted.

Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 328-29.

Parsons, Richard. “Ex-president Frederick Merrick.” 1886. Ohio Wesleyan University, Special Collections Department. South Carolina Governor Robert Kingston Scott. National Governors Association. http://www.nga.org/cms/home/governors/past-governors-bios/page_south_carolina/col2-content/main-content-list/title_scott_robert.html Wexner Medical Center, Ohio State University. http://medicalcenter.osu.edu/aboutus/history/pages/index.aspx Winter, Nevin O. A History of Northwest Ohio. Vol. III. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1917. 1387-90. |

|

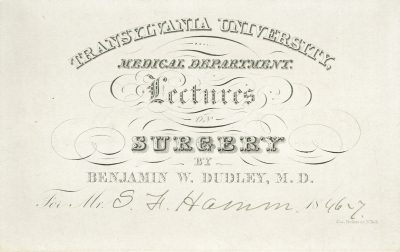

57. Transylvania University (discontinued)

| Transylvania University (discontinued) 1846-47 Dudley, Benjamin W., MD Hamm, S.H. Surgery |

|

|

In 1799 Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, founded the first medical school in “the West.” The Trustees hired the first two professors on a salary basis and allotted $5,000 for books and equipment. Despite attempts to build a faculty and a program, the Medical Department did not gain momentum until 1816-17. Several new faculty appointments around that time included Daniel Drake, MD (Penn; M1816) for materia medica and botany, William H. Richardson, MD for obstetrics and Dudley (Penn; M1804) for anatomy and surgery. By then students purchased lecture tickets directly from professors. During the 1817-18 school year, conflict between Dudley and Richardson that centered on Richardson not actually having a medical degree resulted in a duel. Dudley seriously wounded Richardson, after which he applied first aid that saved his life. The opening of numerous other Midwestern medical schools led Transylvania to close its Medical Department at the end of the 1856-57 school year.

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 328, 338.

Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 289-98. William Richardson, MD. http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Medical_Authors_Faculty/Richardson_William.htm |

|

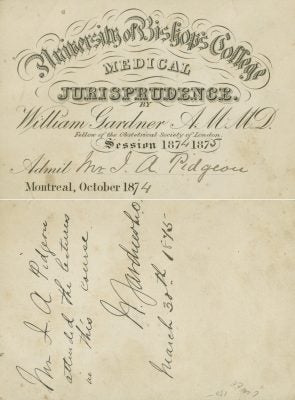

58. University of Bishop’s College (McGill University Faculty of Medicine)

|

University of Bishop’s College (McGill University Faculty of Medicine) 1874 Gardner, William, AM, MD Pidgeou, J.A. Medical jurisprudence |

|

| The Medical Faculty of the University of Bishop’s College, an often-overlooked Canadian medical school, opened in Montreal in 1871 as an English-speaking school. Its founders sought to create an alternative to the monopoly on medical education and hospital privileges held by the Medical Faculty of McGill University. Bishop’s College merged with its rival in 1905. Bishop’s College appointed Gardner (McGill; M1866) professor of medical jurisprudence upon its opening. Four years later Gardner’s alma mater offered him the same professorship. In 1883 McGill separated obstetrics from gynecology and made Gardner its first professor to head the latter. Although he had no surgical privileges or specific training, Gardner taught the subject. Before long he pursued six months of surgical training with British gynecologist Lawson Tait, MD, and returned to McGill. Gardner established a private hospital for his own practice, spent 10 years at Montreal General Hospital, and in 1895 was appointed gynecologist-in-chief to the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Bensley, E.H. “Bishop’s Medical College.” Can Med Assoc J. 1955 March 15; 72(6): 463-65.

Hanaway, Joseph and Richard Cruess. McGill Medicine, Vol. 1: The First Half Century, 1829-1885. Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996. 169-70. |

|

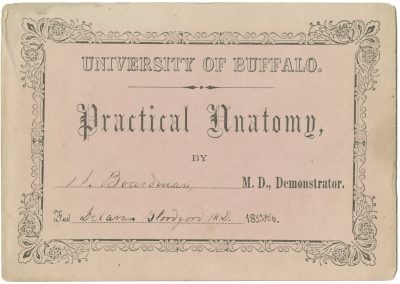

59. University of Buffalo (School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo)

| University of Buffalo (School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo) 1855-56 Boardman, John, MD Bloodgood, Delavan, MD Anatomy |

|

| The University of Buffalo’s medical school was founded in 1846, a time of growth as the Erie Canal transformed Buffalo into a gateway to the West. In 1962 the institution merged with the State University of New York system. Boardman studied medicine for two years at Buffalo, but in 1853 earned his degree from the University of Pennsylvania with a thesis on “Comparative Anatomy of the Eye.” He returned to Buffalo, where the Medical Department appointed him demonstrator of anatomy, 1854-58. Boardman served as physician to the Buffalo Orphan Asylum, attending surgeon to the Buffalo Hospital of the Sisters of Charity, president of the Medical Society of the County of Erie, and member of the board of managers of the Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane. Bloodgood (Jefferson; M1854) took postgraduate courses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, University of the State of New York, and the University of Buffalo before started his 36-year Navy career in 1857. (For more on Bloodgood, see 32.)

Obituary of Dr. John Boardman. Buffalo Medical Journal. Vol. 38. August, 1898, to July, 1899. 67-69

School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. http://medicine.buffalo.edu/about/history.html University of Pennsylvania, Department of Medicine, Class of 1853. Medical Commencement of the University of Pennsylvania, held April 2, 1853: with a Valedictory Address. |

|

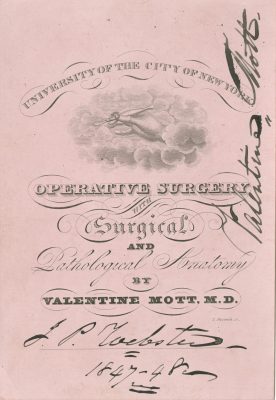

60. University of the City of New York (New York University)

| University of the City of New York (New York University) 1847-48 Mott, Valentine, MD Webster, J.P. Surgery and pathological anatomy |

|

| The University of the City of New York (renamed New York University in 1896) was founded in 1832, its Medical Department in 1841. The University’s charter authorized graduates to practice in New York without receiving a license from state or county societies. Mott (Columbia; M1806) trained with surgeons in London and Edinburgh after receiving his medical degree. Upon returning to NY he taught surgery at his alma mater and in 1826 helped found Rutgers Medical College in New York City. He served with the original medical faculty of the University of the City of New York, retiring in 1850. Mott, “the father of American vascular surgery,” performed the world’s first reported attempt to ligate the innominate artery for aneurysm, the first successful ligation of the common iliac artery in the US, and several other operative milestones. He counseled his students, “Allow me to urge you when about to perform an important surgical operation to ask yourselves solemnly whether, in the same situation, you would be willing to submit to it.”

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 828.

Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 134-38. Rutkow, Ira M., MD, MPH, DrPH. “Valentine Mott and the Beginnings of Vascular Surgery. Arch Surg. 2001;136(12):1441-1441. |

|

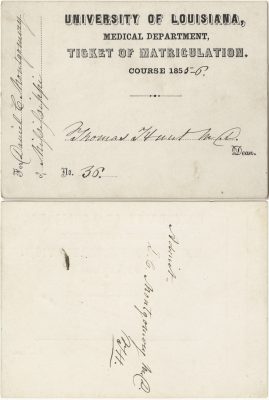

61. University of Louisiana (Tulane University)

|

University of Louisiana (Tulane University) 1855-56 Hunt, Thomas, MD (dean) Montgomery, Daniel, MD Matriculation ticket |

|

|

A native of Charleston, Hunt received his Penn medical degree (M1829), studied in Paris and returned home to practice. In 1834 he and six other physicians founded the Medical College of Louisiana (the second medical school in the South) in New Orleans, a city plagued with cholera and yellow fever epidemics. Hunt served as its first dean and professor of physiology and pathological anatomy. In 1847 the state legislature reorganized the Medical College as the University of Louisiana, a public university. It closed during the Civil War and when it reopened, Hunt served as president of a financially struggling institution. In 1884 it became privatized as the Tulane University of Louisiana. Montgomery, who hailed from Mississippi, also had received his medical degree from Penn (M1855) and then returned to the South and enrolled in classes at the University of Louisiana. Philadelphia, the southernmost Northern city, had attracted large numbers of Southern medical students prior to the escalation of hostilities between North and South.

Field, Beatrice M., assisted by Mary S. Ingraham, 1983, and additional research by Amanda R. Rittenhouse, 2002. Potpourri: An Assortment of Tulane’s People and Places. http://tulane.edu/alumni/upload/potpourri.pdf

Tulane University History. http://tulane.edu/about/history-and-traditions. |

|

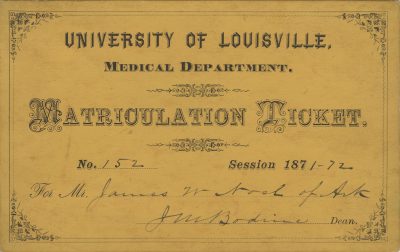

62. University of Louisville

| University of Louisville 1871-72 Bodine, James M., MD (dean) Noel, James W. Matriculation ticket |

|

| The Louisville Medical Institute, established in 1837, became the Medical Department of the newly formed University of Louisville in 1846. The school attracted medical students from the South and West. Bodine (Kentucky School of Medicine; M1854) served as dean for 44 years, overseeing a period of reforms in medical education at the school and shepherding the union of Louisville’s several medical schools into one. He taught anatomy and was preceptor to Simon Flexner (brother of Abraham who authored the “Flexner Report”). As dean, Bodine granted Flexner a break on tuition fees that enabled him to complete his degree and eventually move on to head the Rockefeller Institute. In 1876 Bodine spearheaded organization of the Association of American Medical Colleges. James W. Nowell received his Louisville medical degree in 1873.

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 116.

University of Louisville. The History of the School of Medicine. http://louisville.edu/medschool/about/history/ |

|

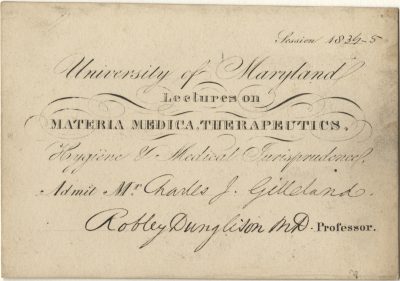

63. University of Maryland

|

University of Maryland 1834-35 Dunglison, Robley, MD Gilleland, Charles J Materia medica, therapeutics, hygiene and medical jurisprudence |

|

| The 1807 the College of Medicine of Maryland opened; five years later it was re-chartered as the University of Maryland, creating the nation’s first public medical school. Born in England, Dunglison studied medicine in London, Edinburgh, Paris and Germany, where he received his medical degree from the University of Erlangen (M1823). When Thomas Jefferson was planning the University of Virginia, his representative sailed to England to hire faculty. He offered Dunglison the professorship of anatomy and medicine, a position he commenced in 1825. Dunglison also served as Thomas Jefferson’s personal physician and in time took care of Presidents Madison, Monroe and Jackson. He joined the Maryland faculty in 1833 as professor of materia medica; his course encompassed therapeutics, hygiene and medical jurisprudence. Three years later Dunglison left Maryland for Jefferson Medical College. Gilleland, a Pennsylvanian, took medical courses at Penn before matriculating and graduating from Maryland (M1835).

Geddings, Eli, MD, editor. Medical and Surgical Science. Vol. II. Baltimore: Carey, Hart & Co., 1835. 70.

Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 223-41. University of Virginia. Robley Dunglison, M.D. (1798-1869). http://www.hsl.virginia.edu/historical/uva_hospital/dunglison/index.cfm |

|

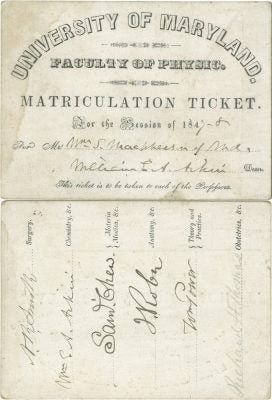

64. University of Maryland

| University of Maryland 1847-48 Aiken, William S.A., MD (dean) MacPherson, William S. Matriculation ticket |

|

| In 1848, a year coinciding with this matriculation ticket, the University of Maryland became the first American medical school to make anatomical dissection a compulsory part of the curriculum and it became one of the last to switch from a bachelor of medicine degree to a doctorate. The front of the ticket reads, “This ticket is to be taken to each of the Professors.” Five professors signed the back: Drs. Nathan Ryno Smith (surgery), William S.A. Aiken (chemistry), Samuel Chew (materia medica), Joseph Roby (anatomy) and William Power (theory and practice). MacPherson (Maryland; M1847) practiced in Frederick County, Maryland. Having Southern sympathies, he received a commission from Stonewall Jackson to be a surgeon in the Confederate Army, but ill health kept him out of service. After the war he was elected Maryland’s Superintendent of Labor and Agriculture.

Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series). William S. McPherson. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013100/013173/html/msa13173.html

Kelly, Howard A. and Walter L. Burrage. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore: The Norman Remington Company, 1920. 215, 934, 989. Norwood, William Frederick. Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War. Phila: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. 223-41. |

|

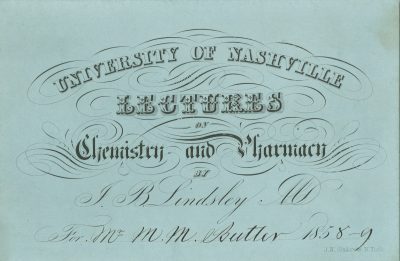

65. University of Nashville (Vanderbilt University)

| University of Nashville (Vanderbilt University) 1858-59 Lindsley, John Berrien, MD Butler, Matthew M. Chemistry and pharmacy |

|

| Lindsley (Penn; M1843) helped establish the University of Nashville Medical Department in 1850 and served as its first dean and professor of chemistry and pharmacy. From 1850 to 1854 the University, except for the medical school, shut down due to a cholera epidemic. By 1859 the University of Nashville was the nation’s third largest medical school. During the Civil War Lindsley served as post surgeon of Nashville hospitals and protected the University of Nashville’s library and laboratory from the occupying Union army. While he manned the home front, his former student, Butler, joined McDowell’s 37th Regiment of Virginia Volunteers. Ironically, Butler had not completed his medical studies in Nashville, but on the eve of the Civil War, graduated from Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College (M1860). He assisted in the amputation of Stonewall Jackson’s arm after the Battle of Chancellorsville and kept surgical instruments used in that procedure as souvenirs. In 1875 the Medical Department of the University of Nashville became part of the new Vanderbilt University.

Phillips, Victor, N. Bristol, Tennessee/Virginia: A History, 1852-1900. 404.

Sullivan County Biographical Sketches, Surnames A thru H. Transcribed by Fred Smoot from History of Tennessee. The Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1887. 1300-1307. http://www.tngenweb.org/records/sullivan/history/goodspeed/bios-1.html The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. “John Berrien Lindsley.” http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=793 |

|