Introduction

The NCAA, first established in 1906 as the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, consolidated the governance of collegiate sports under one body. In the decades prior, however, each Penn varsity sport fell under the jurisdiction of separate Intercollegiate Associations.

Alongside other universities in the Northeast, Penn served as a member of Intercollegiate Associations for each of their sports, including rowing, track and field, cricket, baseball, and football. Each association was composed of different member schools. Delegates from each university would meet, often at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in Manhattan, to set schedules and negotiate rule changes. Membership to these associations was ever-changing, and conflicts between individual schools often would lead to issues in the governing of the sport.

Ultimately, it was the instability in the rules of intercollegiate football that exposed the need for the oversight of a governing athletic body.

Penn's Early Sports Associations

The oldest collegiate athletic body in the United States was the Rowing Association of American Colleges, formed in 1871. Penn’s crew served as a member until 1891, when the Quakers joined with Cornell and Columbia to form the Intercollegiate Rowing Association. The Association’s first annual regatta was held in 1895 on the Hudson River in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. Penn’s Varsity Eight boat won the championship regatta in 1898, 1899, and 1900.

The Red and Blue track and field team was a member of the Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America (IC4A) since its inception in 1876. At the IC4A’s annual field meeting, member schools would compete in events such as the 100-yard dash, 1 mile run, hurdles, high jump, bicycle race, hammer throw, and more. Nicknamed the “Mott Haven Games” after the locale where they were held, the competition was dominated in the early years by Harvard and Yale. The Quakers did not see their first intercollegiate track championship until 1897, but once the dam was broken, the team went on to win three consecutive titles.

The Red and Blue found success almost immediately in intercollegiate cricket. Alongside Harvard, Haverford, and Columbia, Penn founded the Intercollegiate Cricket Association in 1881. Penn students had been playing the game since 1842, and dominated the early years of competition, winning the intercollegiate championship seven times between 1882 and 1888.

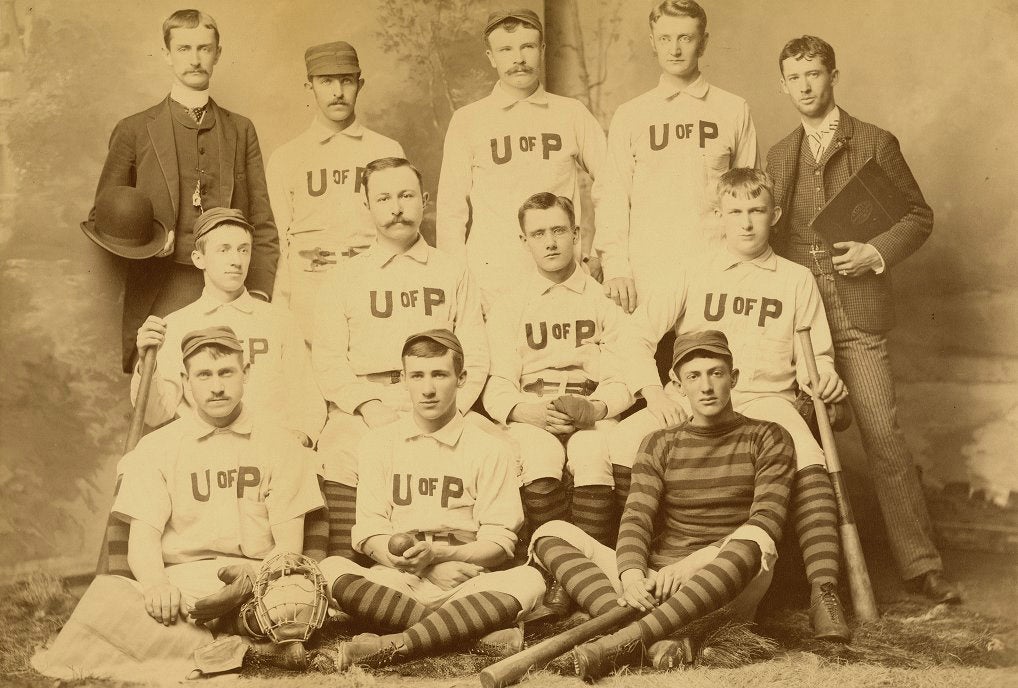

Penn continually found itself left on the outside of formal intercollegiate baseball alliances in the late 19th century. In 1886, the Intercollegiate Baseball Association, established eight years prior, rejected Penn’s petition for membership. At the time, the Association was composed of Brown, Harvard, Dartmouth, Amherst, Princeton, and Yale. Both Penn and Williams applied for membership at a meeting of the Association, and were rejected by votes of 4-2 and 5-1, respectively. Only Brown and Princeton voted in favor of Penn joining the group’s ranks.

Despite being rejected from the group, the Quakers’ nine played against every member of the Association but Dartmouth that season, putting up a record of 11-9.

The Intercollegiate Baseball Association was dissolved at the end of the 1886 season, and the following year, Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Columbia organized the College Baseball League. Penn was again refused admittance in 1888. Ultimately, in 1889, Penn teamed up with Columbia, Lafayette, and Brown to form their own baseball league.

The Intercollegiate Football Association

Penn was formally admitted to the Intercollegiate Football Association in 1885, joining Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Wesleyan as members. In the early years of their membership, Penn and Wesleyan were the clear underdogs of the organization. The Quakers lost consistently to Harvard, Princeton, and Yale by wide margins, even dropping one 1886 contest to the Bulldogs by a score of 75-0.

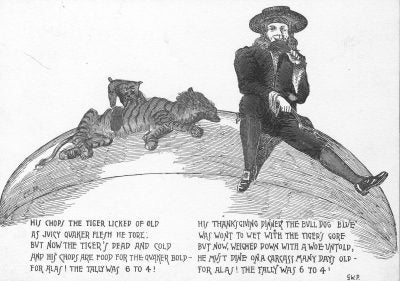

However, Penn’s fortune started to change after George Woodruff arrived in 1892 to take the helm of the Red and Blue eleven. That year, Penn beat Princeton for the first time, winning by a score of 6-4 in front of 15,000 fans.

Penn’s victory over the Tigers marked a turning point in their role in the Intercollegiate Football Association. The so-called “Big Three” of Harvard, Princeton and Yale could no longer consider them an easy victory on the gridiron.

However, Penn’s growth in potential was not welcomed by the three established powerhouses. In the aftermath of Penn’s victory over Princeton and their second-place finish in the Association, local newspapers began to discuss Yale’s plans to dissolve the league and form either a dual league with Harvard, or a tripartite football league with Harvard and Princeton. On Nov. 10, 1892, The Ledger wrote:

To form a dual league now would be an acknowledgement of the fear on the part of these two colleges of the rising football colleges, and to now withdraw from competition with worthy rivals and draw about them with worthy rivals and draw about them the mantle of exclusiveness would be a most nauseating spectacle to a fair and sport-loving public.

Ultimately, Princeton and Harvard never came to an agreement with Yale, and the Association survived.

The Bulldogs turned to different tactics to stifle Penn’s growing football talent. At an Intercollegiate Football Association meeting in 1893, Yale proposed legislation outlining new football eligibility rules. Under Yale’s motion, all students who had matriculated at another college previously would be barred from competition, and only undergraduates would be permitted to play.

At the time, athletic teams were composed of both undergraduates and students in professional schools. A bachelor’s degree was not necessary for admission to medical, dental, or law school, so often these students were close in age to undergrads.

Although almost all big universities used at least one graduate student on their athletic teams, the undergraduate resolution would affect Penn the most. Of the Quakers’ eight returning football players, only two would be permitted to play under Yale’s proposed regulation.

Yale, Princeton, and Wesleyan voted in favor of the undergraduate rule, while Penn and Harvard protested against it. Their disagreement with Yale’s rule drove Penn and Harvard into a closer relationship, resulting in an agreement to play a game together annually on Thanksgiving, alternating locations between Cambridge and Philadelphia.

However, even Harvard and Penn joining together was not enough to override the undergraduate rule. Rather than give in to Yale and debilitate their eleven, Penn withdrew from the Intercollegiate Football Association in 1893.

Penn’s game against Yale was still played that November. The Bulldogs won, 14-6, but this game was still an improvement for Penn; it marked the first time in several seasons that the Quakers had scored on Yale’s eleven.

The fractured Association led to confusion and inconsistent football rules in 1895. Almost every school agreed that changes were needed. On Dec. 11, 1893, The Ledger wrote:

For a number of years past we have had no healthy legislation, for the reason that each college has looked upon the other with more or less suspicion, and, when a college came forward in the Convention with some changes in the playing rules, the first question the other members asked themselves was, what selfish motive is covered up in this proposed change?

However, new football rules just became another point of contention between the universities. Harvard, Penn, and Cornell introduced a new set of rules, while Yale and Princeton devised a new, separate code of their own.

The new Harvard, Pennsylvania, and Cornell rules only slightly changed the game. Under the new code, the back that caught a punt would not be allowed to run with a ball, thereby eliminating open field running from the game. The point of this change was to protect the back from being tackled while in a vulnerable position. Other rule changes included raising the number of officials at a football game to four.

Yale and Princeton’s set of rules also aimed to eradicate roughness from the game, but their changes were much more radical. The rules intended to cut out what they termed “mass and momentum plays.” According to the University Courier on Oct. 2, 1895,

Yale and Princeton by their rules this year disallow the possibility of men forming behind the line in larger numbers than three and require that but one man starts before the ball is in play.

The Courier noted issues with Yale and Princeton’s proposed code:

When we consider the runner advancing with little protection and the tacklers able to cut off and stop readily this interference but one result can be imagined: that the ball will be very difficult to advance. This will result in frequent kicking and catching; here the Princeton and Yale code is at fault. More injuries last year resulted from players being tackled while catching the ball than from any other cause. They have made no restriction whereby the catching back is protected, and with the increased amount of work which he will be compelled to do, injuries, instead of decreasing, will likely increase.

Ultimately, the two groups were playing two different games, presenting yet another obstacle preventing them from meeting on the gridiron. Penn never met Princeton and Yale in 1895. In fact, the relationship had soured such that the Quakers did not face either team in football for decades. The next Penn-Yale contest wasn’t until 1925, and the next Penn-Princeton game was held in 1935.

Professionalism Protests

Although Penn and Harvard refused to be subjected to Yale’s undergraduate rule, there remained a question of what constituted athletic eligibility. Almost all colleges favored the prohibition of “professionalism” — collegiate teams being represented by professional athletes.

In the early 1900s, each university was required to institute and govern their own eligibility code. However, if another institution suspected an opposing team’s player to be ineligible, they could protest that player. Protests were most common in cases when football players were found to have played at the collegiate level for more than four years, or when baseball players were discovered to have played on professional summer teams. The rules were often inconsistently applied, and when a team did protest another, it was often a significant source of tension.

In 1902, Yale protested Harvard’s star tackle, Oliver Cutts. Cutts was ultimately declared ineligible for football on the grounds that he had once taught boxing for money, making him a professional athlete in the eyes of Harvard’s Athletic Committee. Harvard then returned the favor by protesting Yale’s tackle, Edgar Glass. It was discovered that Glass had played two years of football for the University of Syracuse before his two years at Yale, and therefore under the four-year eligibility rule, he was barred from the gridiron.

These back-and-forth disputes exposed the need for a consistent legislative body to resolve them. A Philadelphia newspaper, The Public Ledger, on Dec. 16, 1902, wrote:

One of the absolute necessities of college sport of today is a governing body to decide all questions of athletic eligibility constantly arising among the different institutions of learning in the East. Close followers of college athletics have had this need brought forcibly to their attention by serious disputes that have threatened the severance of athletic relations between universities, the bone of contention having been the status of an athlete.

President Theodore Roosevelt Helps Save Football

It was clear that petty squabbles between colleges was untenable for the organization of college football. Without the oversight of a neutral body, eligibility codes and the rules of football itself became a manifestation of universities’ disputes. But there was also another obstacle that threatened the future of collegiate football: the inherent danger of the game.

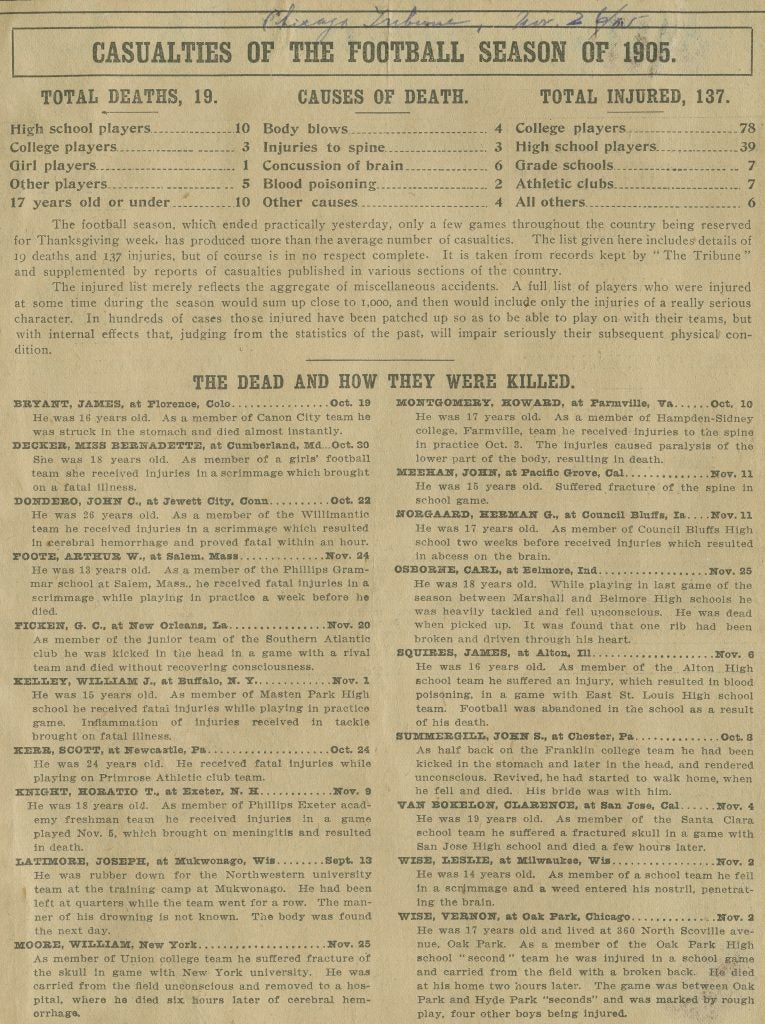

In total, over the 1905 football season, 19 football players were killed, and 137 were seriously injured. The list of casualties included 10 high school players, three college players, and one female player.

The debate over the danger of football was inflamed by an article written by the president of Harvard, Charles Eliot, in 1905. Published in the November edition of Success Magazine, the article advocated for the abolition of collegiate football. Eliot’s criticisms of the game included the large proportion of injuries to players and negative impacts on academic life due to the overt publicity of the sport.

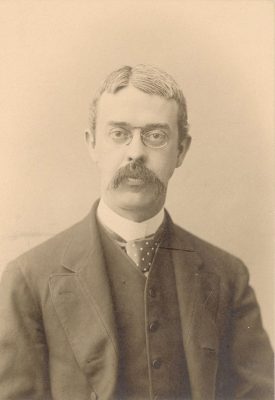

Professor of Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania medical school and a supporter of Penn Athletics, J. William White, responded to Eliot’s article with one of his own, published in Outlook on Nov. 18, 1905. White acknowledged that rule changes were needed to increase the safety of football, but argued that the criticisms raised by Eliot were for the most part exaggerated. White wrote:

Football, the most popular and the most interesting intercollegiate competitive sport, has been brought into court again and again. Some of the charges presented have already been fully answered. Some of them are unjust and incorrect. Some of them are open to radical differences of opinion based upon opposing points of view.

Following the publication of these articles, President Theodore Roosevelt invited White to the White House to discuss the future of collegiate football. The President had a personal stake in the danger of the game; his son, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., played for Harvard’s freshman team, and suffered a broken nose in a game against Yale. In their meeting, Roosevelt made it clear to White that he did not want football abolished, but wanted a uniform eligibility code and for brutality to be eradicated from the game.

Following White’s meeting with the President, Penn issued a circular to all leading football schools in the United States to gauge interest in football reform. The Intercollegiate Rules Committee met in Philadelphia on Dec. 9, 1905, with Penn, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, the University of Chicago, and Navy all represented. The leader of the group was Yale’s representative, Walter Camp, former Bulldog captain, who was reluctant to commit to sweeping rule changes.

Disillusioned with Camp and his old boys’ club of elite eastern colleges, a separate group called the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States formed. Public opinion had begun to turn against Camp, and the final nail in the coffin was Roosevelt’s refusal to endorse the IRC, although he agreed to support a joint committee.

The two committees merged on Jan. 15, 1906. Ultimately, football received a list of new rules on Mar. 5, 1906. The changes included a clearly outlined definition of what constitutes a fair catch, and forward passing was allowed. Also, holding, tripping, and hurdling — jumping over opposing players — were explicitly banned.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association

In 1910, the IAAUS adopted its current name, the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The IRC did not go out of commission until 1916, when the last remaining member, Navy, switched allegiances to the NCAA.

Penn has been a member of the NCAA since the beginning. The Quakers’ relations with Harvard deteriorated in 1905, and they were still on the outs with Princeton and Yale, so the Red and Blue were in dire need of quality competition on the gridiron, motivating their decision to switch from the IRC. Dartmouth was also an original member.

Columbia and Harvard joined in 1909, Princeton in 1913, Yale in 1915, and Cornell followed in 1920. Brown, the final member of what would later become the Ivy League, joined the NCAA in 1929.

Gradually, the NCAA extended their influence into sports other than football. The NCAA’s first national championship event occurred in 1921, as the National College Track and Field Championship.

Sources

The Alumni Register 10 (1905-1906).

Bernstein, Mark F. Football: The Ivy League Origins of an American Obsession. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Orton, George W., ed. A History of Athletics at Pennsylvania, 1873-1896. Philadelphia: The Athletic Association of the University of Pennsylvania, 1896.

Rottenburg, Dan. Fight On, Pennsylvania: A Century of Red and Blue Football. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1985.

Sims, John Clarke, Scrapbooks, 1883-1902. UPS2 S614. University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania.

White, J. William, Papers, 1871-1925. UPT50 W585. University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania.