Introduction

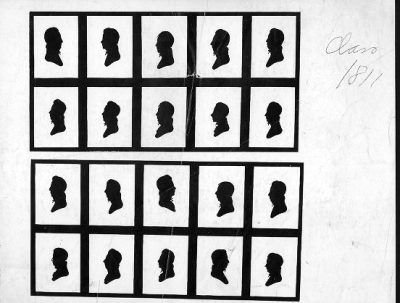

The College Class of 1811 is a rewarding group to examine for a number of reasons. First of all, there are the silhouettes created by Charles Willson Peale at his Museum in Philadelphia. The University Archives has the set owned by Benjamin Gratz, to whom two are inscribed, and a third (his own) is labeled as a copy; three of these silhouettes have been mutiliated but nineteen survive, one of a member of the Class of 1812 and the others of members of the Class of 1811.

The College Class of 1811 is also interesting because of what it reveals about the state of college education in early 19th century America as well as about Penn’s college experience at that time.

Republican educational ideals versus realities

At the founding of the republic there had been much talk of the value of education in creating and maintaining a successful democracy and colleges were founded in significant numbers during the 1790s. In reality, however, unless a young man wanted to become a clergyman, doctor, lawyer or professor, there was not a big financial advantage to continuing education at the college level, and a college degree was not even a requirement for entering medical school or studying law. Soon there were far more spots for college students than there were students to fill them and colleges found themselves struggling to keep enrollments high enough to bring in enough tuition to pay their faculty and maintain their campuses.

Pressures on colleges

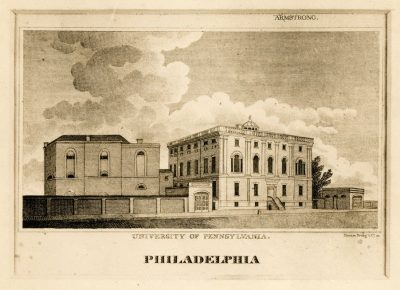

As colleges in general struggled to stay afloat given this insufficent applicant pool, requirements for both entry and graduation declined. The University of Pennsylvania in 1801 opened a second campus on Ninth Street for its College and Medical Department, while still maintaining the original Fourth Street campus for its Academy and Charity School. Having low College enrollment was definitely underutilization of an expensive new building, a burden when the University was now supporting two campuses.

There was pressure in many colleges to accept younger students, with less training in the classics and mathematics. To attract students, colleges sometimes even made it possible for students to get their degrees in two years rather than the then-customary three years of attendance. The trustees minutes show that, at Penn, several classes in the first decade of the 19th century were allowed to skip their last year in the Academy to proceed directly into the College; and the College had no graduating class at all for three of the first ten years after the move to the Ninth Street campus. To make ends meet, trustees sometimes required professors to teach more subjects and to take on other assignments; at Penn, this included giving College faculty more administrative duties as well as requiring them to teach more Academy classes. Worried trustees often upset professors by their micromanagement of curriculum, teaching assistants, and discipline.

Faculty also felt pressured to put up with more students cutting classes and even defying teachers. At the University of Pennsylvania, student conduct would be a special concern during the first decades of the nineteenth century, but at least until 1811, the trustees and faculty were relieved not to have the problems of students acting out that were endured by some other institutions, such as nearby Princeton. The trustees minutes from the time do show that Penn’s College did have to deal with both reduced college enrollment and young college students sometimes cutting class. To find out more about these trends, consult Rodney Hessinger’s book, Seduced, Abandoned and Reborn (2005).

Academic life for the College Class of 1811

The College student body was indeed small, only twenty-one students graduated in 1811- and that was a big class for the time. These students in the Class of 1811 were also young, but varied in age; at graduation their mean age was 19, with the youngest only 15 and the oldest 22 years of age. This small student body shared the University of Pennsylvania’s new Ninth Street campus with the much larger Medical School ; and the College students shared their faculty with the considerably larger Academy, still located with the Charity School at the original Fourth Street campus.

A look at the entrance requirements and the curriculum makes it clear that the students in the Class of 1811 were studying far different subject matter than is taught to students today. Headings such as “moral philosphy” and “natural pholosophy” seem strange to us today, and the emphasis on reading Greek and Latin authors and on oratory and theology would make many current students uncomfortable. Attendance at class was important partly because there were few textbooks; instead students were expected to write down verbatim what the professor lectured.

Life outside the classroom

In the early nineteenth century, College students at Penn, and elsewhere, not only experienced an academic life very different from that of college students today, they also had no extracurricular life to speak of. There were no organized sports – Penn’s first sport, cricket, did not appear until 1842; crew began in 1854, followed by baseball in 1865, track in 1873 and football in 1876. The first Penn fraternity, Delta Phi (St. Elmo), was not organized until 1849. Some colleges had dormitories on campus, but there were no dormitories on the Ninth Street campus and there would be no dormitories until the construction of the Quad beginning in the 1890s; about half the class was from Philadelphia and most likely lived at home; others lived in the homes of friends of the family or in respectable boarding houses.

There is a hint in surviving documents that students in the College Class of 1811 were beginning to coalesce outside of the classroom around literary pursuits; a published text survives of Alfred H. Dashiell’s oration delivered before the Hermean Society at the University in commemoration of Washington’s birthday. No information survives about this Hermean Society, and there is no record of any other such organizations students might have been involved in at that time. However, in 1813 – only two years after the 1811 commencement, members of the College Class of 1815 formed the Philomathean Society, a society intended to encourage the advancement of learning that survives to this day.