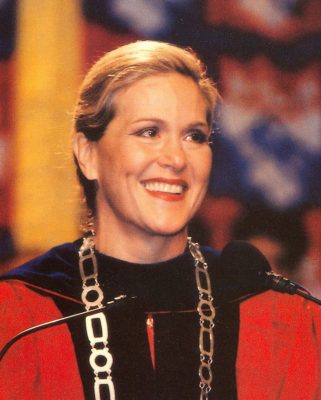

When faced with the task of electing a new president at their 16 December 1993 meeting, the Trustees chose Judith Seitz Rodin. She became the first permanent female president of an Ivy League Institution when she took office on 1 July 1994. Rodin not only offered her extensive knowledge and experience as an educator and administrator, but also, as a Penn alumna, demonstrated a real commitment to the University. Rodin became the unanimous choice to succeed Sheldon Hackney and to relieve Claire Fagin because,

From the beginning of her tenure Rodin made it her goal to strengthen undergraduate, graduate, and professional education, rejuvenate both the campus and the surrounding community, increase funding for the University, and strengthen Penn’s national and international reputation. Her strategic planning efforts successfully led Penn into the 21st century.She [had] the highest academic values and the planning and management skills to put them in effect. Even more important she [had] the interpersonal skills, the political and social sensitivity, indeed, the charisma, to inspire others to join in the formation of goals for the University and their attainment.

The Rodin administration first committed itself to revising undergraduate education. In October 1994 Rodin and Provost Stanley Chodorow published in the University Almanac an overview of a program titled “Implementing a 21st Century Undergraduate Education.” In this brief outline, Rodin and Chodorow revealed their plans to promote fluid interaction among the various schools and to create a closer relationship between research and teaching; living and learning; and the professional school faculty and undergraduate education. They also identified eight principles that guided their plans for undergraduate reform: institutional distinction; faculty-centered instruction; and an overall experience that would be intellectually engaging, research oriented, residentially integrated, interdisciplinary, broad and international. Rodin and Chodorow anticipated that the initiative would take three years to complete.

The 21st Century Plan for Undergraduate Education soon became identified with a larger, five-year strategic plan that engaged Rodin’s efforts for the bulk of her tenure. The Agenda for Excellence, first described by the Trustees at their meeting on 15 December 1995 meeting, named undergraduate education as a central area for revision, along with graduate and professional education. The Agenda for Excellence was unique because it called for the improvement of educational programs while also recognizing Penn’s role as an urban institution that could only realize its full potential by committing itself to improving the surrounding West Philadelphia community. In the Agenda, Rodin and Provost Chodorow related 9 major strategic goals:

- Solidify and advance Penn’s position as a premier research and teaching university in all undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs.

- Aggressively seek greater research opportunities and funding

- Manage human, financial, and physical resources through more effective planning and budgeting and a broadened administrative restructuring

- Support investments in master’s programs

- Plan, direct, and integrate government and community relations to enhance missions of teaching, research, and service

- Pursue efforts to increase Penn’s role as an international institution

- Deploy new technologies

- Better communicate Penn’s contributions to advancements in society

- Secure funds to support strategic goals

Rodin used these strategic goals as a guideline for the reforms she suggested in the plan.

In September 1996 Rodin expanded on the Agenda for Excellence by identifying Six University Academic Priorities. These priorities included: health science, technology and policy; American and comparative democratic and legal institutions; management, leadership, and organizations; the humanities; the urban agenda; and information science, technology and society. The Rodin administration felt that devoting the most energy to these priorities would best enhance Penn’s greater academic environment.

By the time the five-year Agenda for Excellence concluded in 2000, the University had advanced in U.S. News and World Report’s annual ranking of American colleges and universities from 16th (1994) to 6th (2000). The Agenda was largely, if not solely responsible for the faculty accomplishments, increased student selectivity, increased research funding, revitalization of the West Philadelphia community, and the increased globalization that caused this jump. Fundraising alone during the five year Agenda for Excellence totaled $952 million. By the end of the 20th century Penn established itself as one of the premier institutions of higher learning in the world.

The enormous success of the Agenda for Excellence motivated the Rodin administration to use the plan as the basis for a new strategic planning document, published in the Almanac on 23 September 2003. The aptly titled Building on Excellence: The Leadership Agenda picked up where the Agenda for Excellence left off while updating it to fit the new context. Rodin planned to build on Penn’s existing strengths: the world class faculty, human and intellectual diversity, the interdisciplinary environment, the urban context, Penn’s international scope, and the University’s entrepreneurial and engaged spirit. Penn still faced challenges, however: faculty recruitment and retention, globalization, technology, defining higher education in the 21st century, regional and economic development, and financial capacities and constraints continued to demand attention. Like the Agenda for Excellence before it, the Leadership Agenda identified a number of strategic objectives, goals and initiatives that, if achieved, would allow Penn to build on its strengths in the most effective ways possible. The four broadest strategic goals included:

- Maintaining academic excellence

- Capitalizing on differentiating strengths

- Defining the future of education

- Creating the capacity for success

The Leadership Agenda remains in place as the current planning document that will guide Penn through the first decade of the 21st century. Rodin’s legacy will live on through it.

Rodin also tackled physical plant planning during her presidency. On 16 February 2000 the Trustees approved “Campus Development Plan 2001,” a follow-up to the plan first proposed by Rodin, Provost Robert Barchi, and Executive Vice President John Fry in April 1999. The original 1999 plan, also known simply as “Campus Development Plan,” observed that even in spite of the historic and commercial value of the campus, its growth had never really developed from an advanced planning initiative. The University hired Olin Partnership, Ltd., a leading Philadelphia architectural and urban design firm, to prepare the plan. After the two-year study was completed, Olin Partnership came up with three areas to navigate the plan: the academic core of the campus; the campus fabric, including buildings, grounds, streets, and infrastructure; and Penn’s context within the city. The Olin group made six main recommendations for improvement in those areas:

- Strengthen connections across campus

- Create a coherent identity for the whole campus

- Reinforce the historic pedestrian core

- Invest in capital renewal

- Enhance vibrant, historically significant residential communities within University City

- Connect Penn to Center City

The Campus Development Plan supported the academic goals and missions of the Agenda for Excellence. Although it has yet to be fully realized, fulfilling its objectives would provide Penn with a more cohesive physical plant that is both conducive to learning and also extends Penn’s connection to the city of Philadelphia.

When Judith Rodin delivered her inaugural address on 21 October 1994, she spoke of Penn’s “genetic material.” This “genetic material,” according to Rodin, consisted of certain traditions, the most important being Benjamin Franklin’s educational dogma of combining “theory and practice.” Rodin affirmed,

And so, in a sense, the most central tradition that this university inherited from its founder is a certain disdain for tradition – a willingness to challenge orthodoxy and to think creatively and boldly.

Judith Rodin was so successful as the president of Penn because she motivated herself by this central tradition. She was unwilling to accept anything less than the best, as evidenced by her ambitious strategic plans. Judith Rodin catapulted the University of Pennsylvania into a realm it might never have reached without a president with such a far reaching vision.