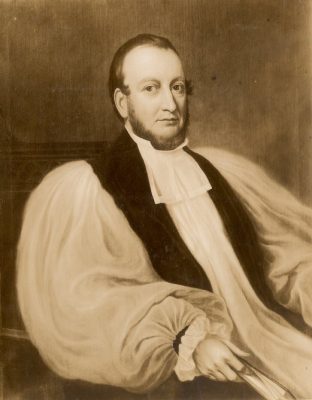

William Heathcote Delancey became Provost of the University of Pennsylvania in 1828.

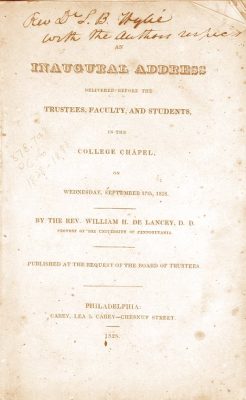

Inaugural Address of the Provost, 1828

Excerpt from the Speech: Opening Remarks

GENTLEMEN,

The circumstances under which we meet at the present period are, in every view that can be taken of them, peculiarly interesting to us all.

To you, Gentlemen of the Board of Trustees, the occasion is one of interest, since it is the opening of that new course of exertion in behalf of the University of Pennsylvania, on which the earnest expectation of an interested community, as well as your own equally earnest desires, are fixed, as the means of its future elevation; and since, by the recent measures of your Board, you stand pledged to the public on the responsibility of your word, honour, reputation, and stewardship, to throw the entire weight of your extended and powerful influence into the scale of the institution of which you are the constituted guardians.

To us, my brethren of the Faculty, the present circumstances are interesting, almost beyond the power of an estimate. For, whether the view be just or unjust, a scrutinizing public invariably associates the prosperity or decline of a literary institution with the character, diligence, and talents, of those who conduct its government and its instructions; and they cannot be deterred from regarding, nor from pronouncing, the measure of the former the certain standard of the latter. To us, then, the present occasion marks the commencement of a career of labour in which not merely our personal and domestic interests, but, to a wide extent, our character and standing with the public, are deeply implicated.

To you young gentlemen, the Students of the University, our present meeting is one of interest, because it is the beginning of a system of instruction and discipline, in some respects new, under the tuition and control of a faculty who are in some degree strangers to you; but who, nevertheless, will cheerfully pledge a paternal interest in your welfare, and their utmost energy in the effort to expand your minds, enlarge your acquirements, and implant the seeds of that knowledge which must be the foundation of your future eminence, respectability, and happiness, in the world.

To the friends of the University, under which term I trust may be included not only the respectable audience whom I now address, but the great majority of the community within the limits of Philadelphia, the present meeting may be prounounced interesting in the extreme. An institution which was originally called into life for your accommodation; and which, however it may retain a nominal, can have no efficient and profitable existence without your patronage and favour, is, we trust, on the eve of resuscitation; and, at this moment, comes forward to ask at your hands, not only a candid interpretation of the measures of its Governors, but a favourable estimate of its present claims; and your countenance to the united exertions of its Trustees and Faculty, to render it, in respect to its future discipline and instructions, as worthy of your support, as it is, in regard to its location, deserving of your favour. Every individual among us, who now sustains, or who shall ever sustain, the endearing and tender relations of a parent, must respond from his inmost soul to the present effort to revive a college, where his sons may attain an adequate collegiate education without encountering the increased expenses, and the moral perils, of an estrangement from the delights, associations, and counsels, of the parental roof.

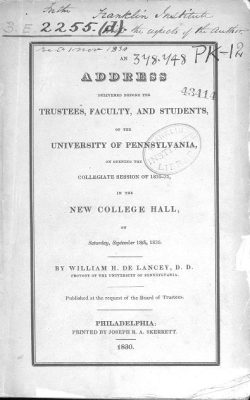

Opening Address of the Provost, 1830

Excerpt from the Speech: Opening Remarks

The circumstances and feelings under which I rise to address this respectable audience on the present occasion, are materially different from those which prevailed when, two years ago, the friends of the University were assembled to listen to the Inaugural Address of the newly-appointed Provost. To the trustees, to the faculty, and to myself it was then the anxious season of commencing a new experiment. In the relation in which we were placed, we were all strangers to each other. The confidence of the board, of the students, and of the public, was to be won. To almost all the faculty the path was new, and wholly untrodden. We could not, however, fail to perceive that a decayed institution was more difficult to be re-invigorated, than a new one established and matured. We could not blind our eyes to the fact, that whatever may have been the causes, the public had but little confidence in the collegiate department of the University, that it was regarded as not even meriting the patronage of the board who controlled it, that the spirit and energy of its pupils had well nigh departed, and in short that we were entering upon the hazardous and uncertain enterprise of restoring vigour, activity, and extended usefullness to a limb of the institution, long benumbed and paralized. We knew, too, the mutability and the coyness of public opinion; that the most faithful and meritorious were not always certain of securing the favour of the changeful and oftentimes capricious damsel whom they wooed; and that the busy and envious tongue of prejudice had often by its jaunticed representations marred and thwarted the best concerted plans and the most energetic efforts. Nor were we too young to foresee that the introduction of more decision and rigour into the discipline of this department would necessarily subject us to the ill-feelings and perturbed views of those on whom its severities might fall, while the natural partialities of parents would induce them to attempt to screen offending offspring by the diffusion of charges and partiality, unnecessary rigour, and injudicious treatment against those on whom was devolved the arduous duty of controlling by moral means alone, vexations dispositions, unsteady tempers, and indolent or reluctant minds.

Without dissembling to ourselves the magnitude, or the number of the difficulties which were in propect, we yet augured success under Providence, from the influence, character, and energy of the board of trustees, and from the persuasion that the community of this city, although slow to award their confidence, would yet not withhold it when convinced that it was fairly merited by the competency, assiduity, and faithfulness of those who sought it.

In this augury we have not been disappointed; and the changes which in the short space of two years have occurred in the state and prospects of the college, afford, I think, ample evidence of the fact. I address you in a spacious apartment of a noble edifice, which has been erected for our accommodation by the zeal and liberality of the board of trustees. I invite your inspection of the rooms of our new college, adorned by increased apparatus for instruction in the sciences. I call to your remembrance the splendid assemblage of fourteen hundred persons who witnessed, with apparent gratification, the ceremonies of our late commencement. I refer to the explicit, spontaneous, repeated expressions of their confidence in the government and instructions of the college, which have been published by the board. I direct your eyes to the collection of one hundred and twenty-five students, breathing the fervid spirit of literary emulation, in place of the twenty-one attached to it when first committed to our charge. I state to you the facts, that the number of Philadelphia youth now receiving a collegiate education is above one-third more than were enjoying that benefit two years ago; that at present not more than twenty of our young men are educated at colleges out of the city, while at the time referred to at least fifty were sent abroad for collegiate education; and that during the last year, as far as can be ascertained by an examination of the annual catalogues of neighbouring institutions, not more than one young gentleman left this city to connect himself with the freshman class of a distant college.

These facts which appear to warrant the assertion that public confidence, long absent from this department of the University, has at length revisited its halls, and may fairly be expected still further to spread over its concerns a fostering wing.

It is with feelings not of the vain pride which centers in self, and ascribes success to its own efforts, but of satisfaction inspired by the public countenance and patronage awarded to our efforts, that in behalf of my brethren of the faculty, I offer our united acknowledgments to this distinguished community, on whose enlightened judgment and support we repose our hopes of raising the college to higher distinction and more enlarged usefulness.