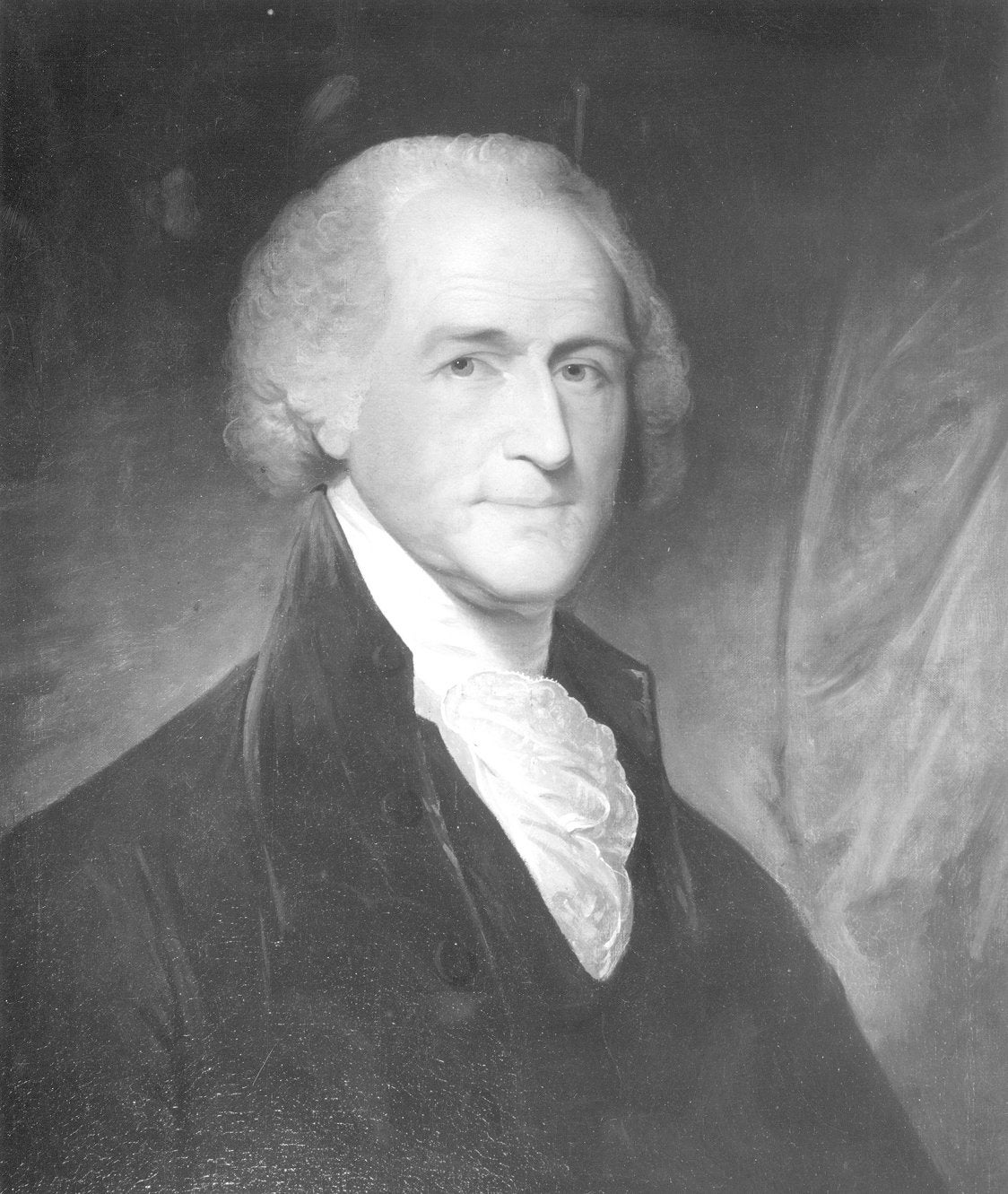

William Shippen, Jr., son of William Shippen and Susanna Harrison, was born in Philadelphia on October 21, 1736. He received a sound classical education intertwined with firm religious guidance at the Rev. Dr. Samuel Finley’s Nottingham Academy. He then went on to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), graduating with an A.B. in 1754. His valedictory address at the commencement exercises of that year impressed Ezra Stiles as an “ingenious oration” and was compared in eloquence to speeches of Roman orators by George Whitefield.

Shippen next served a medical apprenticeship under his father in Philadelphia. In 1758, with financial aid from his uncle, Edward Shippen III, he went to England to study under Drs. John Hunter, William Hunter, and MacKenzie. After completing his dissertation, entitled “De Placentae cum Utero Nexu,” Shippen graduated with a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Edinburgh in 1761. Following a short visit to France, he returned to Philadelphia in May 1762.

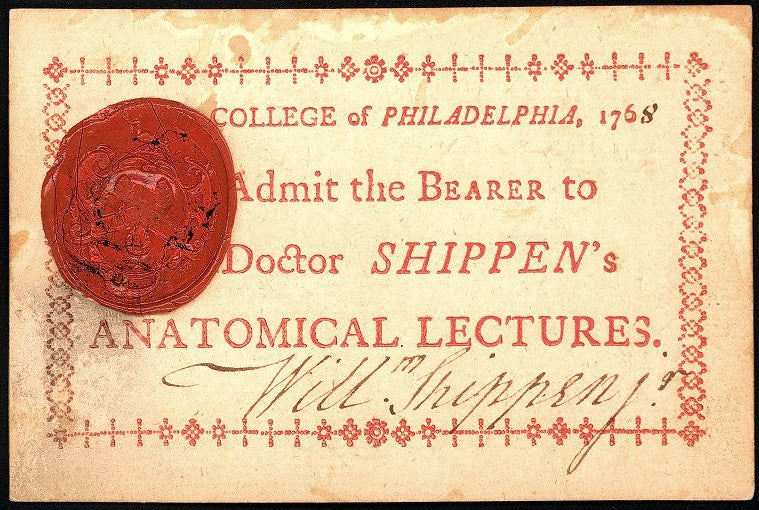

On November 16, 1762, with his father’s assistance, Shippen inaugurated a series of lectures on anatomy, surgery, and the practice of midwifery. His lectures on anatomy were the first ever delivered in America and incorporated anatomical drawings and casts made by the famous Dutch painter, Jan Van Rymsdyk. By 1765, Shippen offered a complete course in midwifery to both women and men. Because many people found male midwifery offensive, rocks periodically shattered the windows in his lab and mobs burst into his dissecting rooms. Despite these controversies, Shippen became increasingly successful and was elected professor of anatomy and surgery in the newly founded medical department of the College of Philadelphia on September 23, 1765.

Although John Morgan is credited with founding Penn’s Medical School, the first in the colonies, Shippen played a key role and was not always pleased to have his contributions overlooked. In 1765, Shippen’s friend John Morgan returned from medical training abroad, three years after the two young men had discussed plans for establishing a medical school in the colonies. Morgan, however, acted alone to implement his “Discourse upon Institution of Medical Schools in America” and was appointed professor of the theory and practice of medicine by the trustees of the College on May 3, 1765. Thus, Morgan, not Shippen, became the founder of the first medical school in British North America and held the first medical professorship. For years he reaped the perpetual enmity of the Shippens, with grave consequences for the development of medicine in the colonies and early republic. Morgan exacerbated the situation in 1766, when he founded a medical society and again ignored the Shippens. Shippen did not agree that medical practitioners trained through traditional apprenticeship methods should be excluded from the emerging profession. The public and private feud over who originated the Medical School and other professional and personal matters divided the medical community until Morgan’s death in 1789.

Although Shippen signed the Non-Importation Agreement during the Stamp Act crisis, he lacked his father’s ardent commitment to the American cause. Private ambitions to advance professionally, socially, and economically help explain his wartime conduct. In July 1776, Shippen became chief surgeon on the Flying Camp in New Jersey. In October, he gained appointment as head of all hospitals west of the Hudson River. Shippen continued to challenge Morgan’s authority during this time. In January 1777, Congress abruptly relieved Morgan of his post as director general of hospitals. In March, it adopted Shippen’s plan for reorganizing the army medical department, and on April 11, appointed Shippen in his stead. Blinded by vindictive rage, Morgan forgot the many causes that brought about his dismissal, and presented his case in Vindication of His Public Character (1777).

In October 1777, Benjamin Rush, a physician and the first professor of chemistry at the College, entered the controversy against Shippen when he publicly expressed concern that “our hospital affairs grow worse and worse… The fault is both with the establishment and in the director general. He is both ignorant and negligent in his duty.” In January 1780, Shippen was arrested and five specific charges were presented. His accusers essentially claimed that Shippen speculated with supplies such as wine and sugar when the sick and wounded needed them and asserted that his incompetence caused needless suffering and death. Shippen escaped conviction by one vote, following a highly irregular trial, during which the board’s composition changed and the accused privately entertained the board members with fine food and mocking imitations of his chief detractor. Shippen’s defense of his conduct confirmed the opinion that he was insensitive to human suffering; as director general, he never visited the sick, dressed wounds, or comforted soldiers. Shippen nonetheless remained in the position until his resignation on January 3, 1781.

Despite the scandal, Shippen’s stature rose. On May 11, 1780, he was elected professor of anatomy and surgery in the newly reorganized University of the State of Pennsylvania. He remained in that position through the subsequent changes of the University until his resignation in 1806. In 1791, Shippen rejoined the staff of the Pennsylvania Hospital and served there until 1802. Shippen was also one of the originators of the College of Physicians in 1787, and served as its president from 1805 until his death. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in November of 1777.

Shippen contributed significantly to the establishment of medicine in America as a profession based on university training. He also pioneered courses in midwifery despite opposition from “the unskilled old women,” whose methods he believed caused needless suffering and sometimes death. He provided scientific knowledge about women’s diseases and appropriate treatments, along with “necessary cautions against the dangerous and cruel use of instruments.”

Shippen married Alice, daughter of Colonel Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell of Virginia, in April 1762 at St. Mary Le Strand in London. The couple had eight children. Shippen died of anthrax on July 11, 1808, in Germantown, Philadelphia.