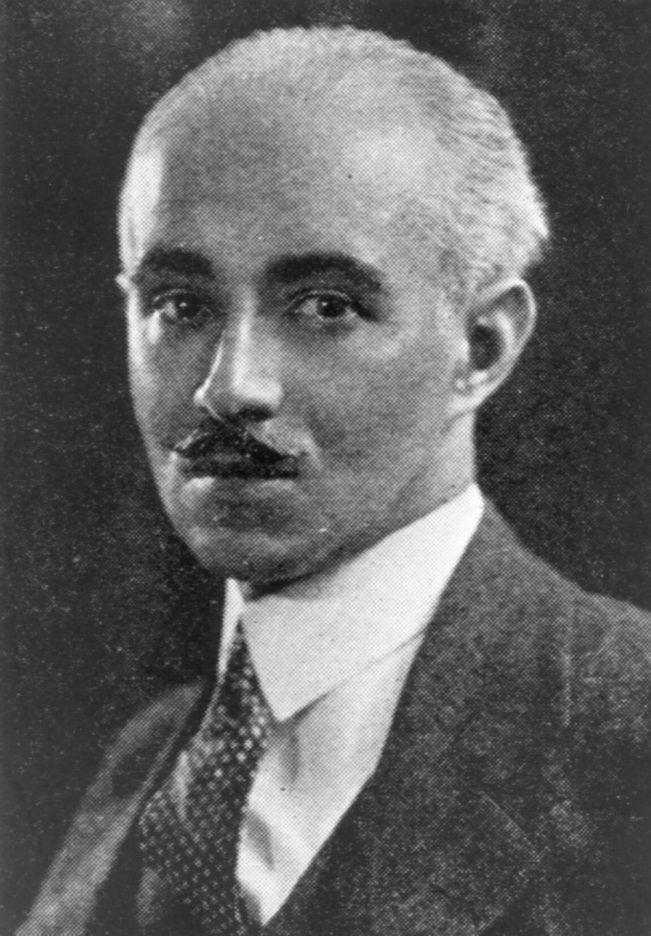

A well-known Philadelphia architectural designer, Abele was the first black graduate of what is today the School of Design. Julian Francis Abele, born in Philadelphia on April 30, 1881, was the youngest of eight children born to Charles and Mary Adelaide Jones Abele. Through his mother Adelaide, Julian was a descendant of Reverend Absalom Jones (1746-1818), founder of the Free African Society and of St. Thomas Episcopal Church. His older brothers included Joseph B. Abele, an engineer with the Philadelphia Electric Company; Robert Jones Abele, who graduated at the top of his 1895 class at Hahnemann Medical College; Charles Abele, a brass sign maker who worked with artisan Sam Yellin.

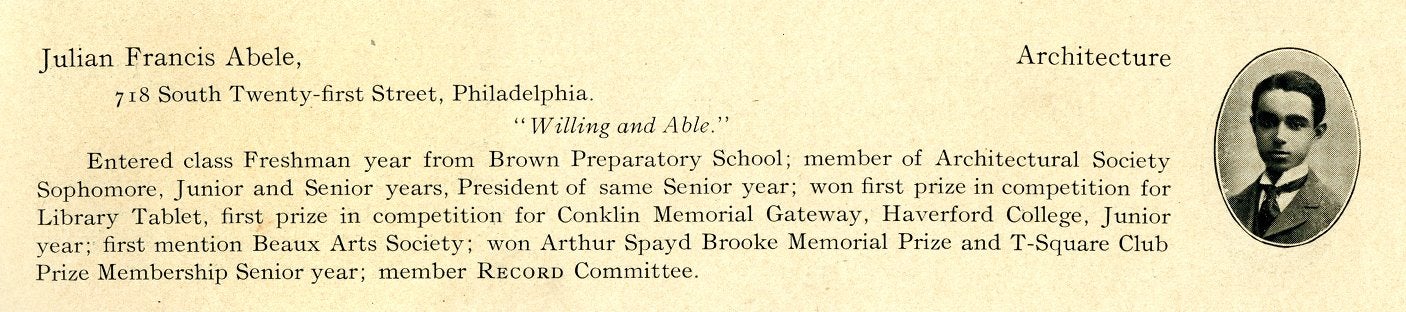

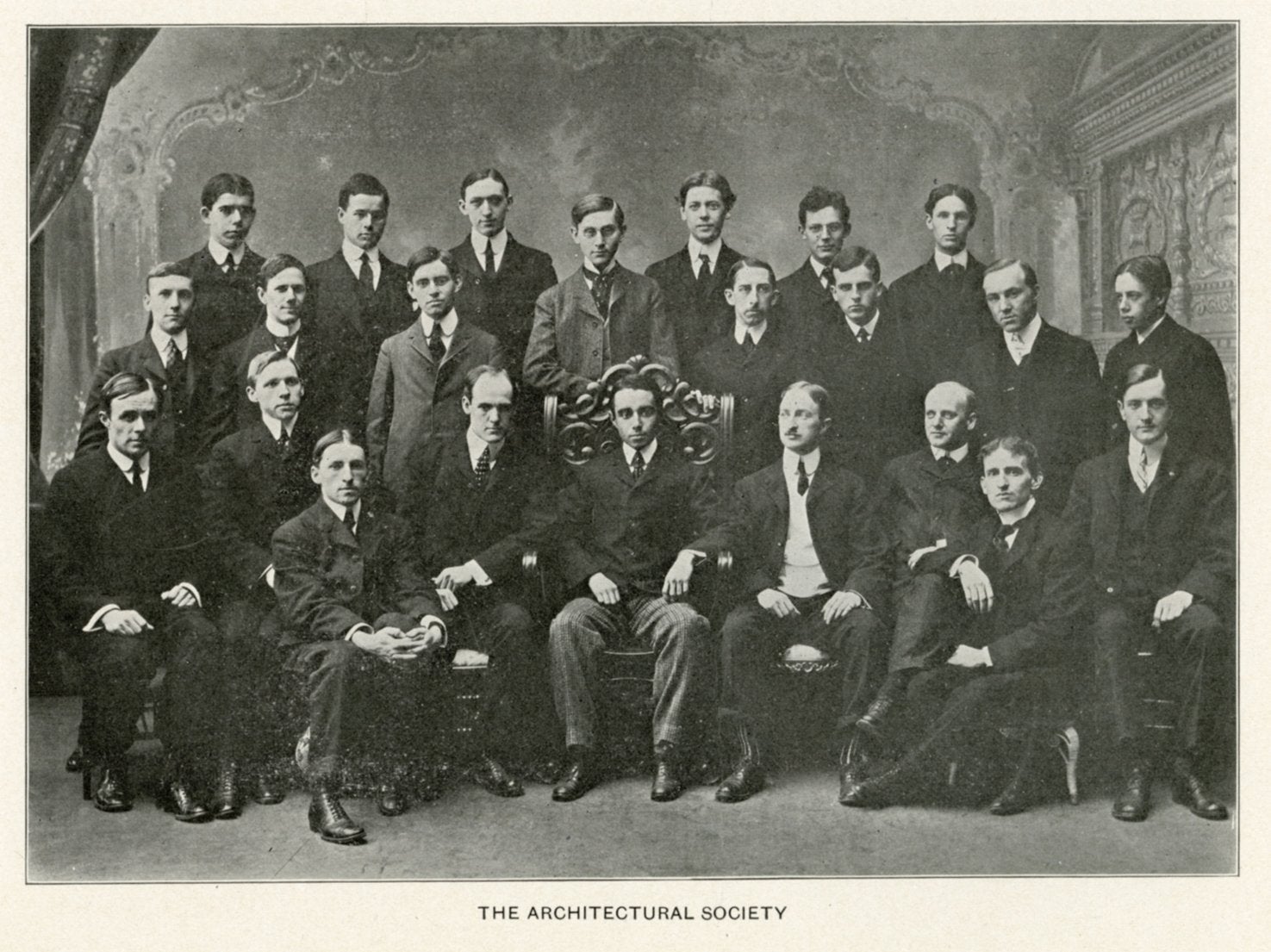

Young Julian Abele was educated at the Institute for Colored Youth, Brown Prep School and the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art before enrolling at the University of Pennsylvania in 1898. An outstanding student, Abele received a number of prizes during his undergraduate years at Penn, including first prize in competition for the Library Tablet to commemorate alumni gifts, first prize in competition for the Conklin Memorial Gateway at Haverford College, first mention from the Beaux Arts Society, the Arthur Spayde Brooke Memorial Prize and the T-Square Club Prize. During his senior year, Abele served on the student yearbook committee and as president of the Architectural Society. He did all this while working all four years as a designer with the Louis Hickman Architectural Firm, juggling his job with afternoon and evening classes at the University.

After graduating from Penn in 1902 with his degree in architecture, Abele was immediately engaged by established architect Horace Trumbauer, who is said to have helped to finance the young architect’s three years European travel and study. There is no record of his study at l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which is sometimes reported, although French architecture would be his lifelong passion. Abele returned to Philadelphia and the Horace Trumbauer firm in 1906. He spent his entire professional life with this large, nationally known firm, advancing to the position of chief designer in 1909 and taking over the office after Trumbauer’s death in 1938. The company was responsible for the design of such Philadelphia buildings as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Land Title Building (which came to house the offices of Trumbauer’s firm), and a number of mansions, including Edward Stotesbury’s Whitemarsh Hall. At Penn, Irvine Auditorium, the Dunning Coaches Center, and the President’s House were designed by Trumbauer’s office, and projects outside Philadelphia included the Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, mansions in Newport and New York and many of the English Gothic and Georgian buildings on the campus of Duke University in North Carolina.

As in any large firm, assigning design credit to individuals is difficult. Abele undoubtably helped to shape all the work that passed through the office, but was not the designer of every project. Among the important buildings that can be confidently assigned to him is the Free Library of Philadelphia, whose design he personally presented to the client and to the city’s design review panel.

Abele had immersed himself in the Beaux Arts style as a student and remained committed to this system of architecture. He was noted not only for his adaptation of historical styles to create fine exteriors, but also for his successful rendering of interior space and its decorative details. Julian Abele’s artistic versatility is remarkable. Not only was he a master architect, he also worked skillfully with wood, ceramics, iron, copper, brass, precious metals stained glass, and water colors. He made furniture, jewelry, paintings and lithographs as gifts for his friends and associates.

Despite Abele’s sophistication, accomplishments and influence as an architect, racism did limit the public recognition of his role in the buildings he was responsible. Racial prejudices deterred him from visiting the Duke University campus he designed and delayed his admission to the American Institute of Architects until 1942.

As a student and his early in his career, Julian Abele resided in the house of his mother Mary Abele (listed as a 55 year old milliner) at 718 South 21st Street in Philadelphia; five of his brothers, a sister-in-law and a niece also lived here at the time of the 1900 census. According to the the 1910 census, ten years later Julian was living in the household of Charles Abele at 1911 Fitzwater Street; also living in the household were two other Abele brothers (one with a wife) and sister Elizabeth Abele Cook and her five children. Elizabeth had separated from her husband, John Francis Cook, in 1906, she and her children would reside with her brothers.

In 1925 Julian Abele married his piano teacher Marguerite Bulle; at age 49, he was twenty years older than his Parisian born bride, a student of conductor, composer and pianist Nadia Boulanger. The couple had three children: Julian, Jr. (the eldest), Marguerite Marie (who died at age five) and Nadia Boulanger. The 1930 census shows Julian, his wife and two oldest children living, along with Elizabeth Abele Cook and her youngest child, at 1515 Christian Street. This 10-room, 3-story rowhouse was furnished with elegant French furniture, objets d’art from their travels plus furniture, art work and even needlepoint from Julian’s hand. In 1936, after Marguerite left Julian to marry another man, the children remained with their father on Christian Street.

Julian Abele died at home in Philadelphia on April 23, 1950. His descendants have continued to gravitate toward architecture. His son Julian Abele, Jr., and his nephew Julian Abele Cook both became architects. Julian Abele Cook studied architecture at Penn with the Class of 1927; two of his grandchildren have continued the family tradition, Susan Cook as an architectural engineer and Peter Cook as an architect in Washington, D.C. Ironically, it was Susan Cook, while a student at Duke University during the 1986 student protests against apartheid in South Africa, who wrote the letter to the student newspaper which made public Julian Abele’s role in the creation of the Duke campus. His portrait now hangs in one of the buildings he designed, and the Duke University Web site proudly acknowledges his work.