The Red and Blue Add White: Patriotism is the Word

On April 6th, 1917, the United States entered a state of war with Germany, and joined the Allied powers in their fight for Europe. To many, this development did not come as a shock. Much of the country was angered by the German disregard for American neutral rights, and thus the national spirit was, for the most part, behind the war. At the University of Pennsylvania, debates about National Preparedness and the need for military training came to a halt, as did questions of whether it was necessary to join the war. The question now became how each member of the community could do his part for his country. Every school and department modified its program of study to serve the war effort in some way. The University took pride in its patriotism and continued to expand its military involvement in new ways throughout the war. All sons of Pennsylvania who made sacrifices for the good of the United States were celebrated.

Changes at the University

The most obvious change to the University during wartime was the loss of students to enlistment. After just the first year of United States involvement in the war, each undergraduate dean reported to the Board of Trustees decreases in enrollment due to war conditions. By the beginning of 1918, the Law School only had 54 students total, owing significant losses in registration to enlistments. The University granted leaves of absence for service in several fields, including the Army, the Navy, Farming, Commissary, the Red Cross, Industry (under Government), Government Wireless Operator, State Police, and Government Telegraph Operator. The largest number of absences granted was for the field of Farming, with the Army and Navy close behind. The University administrators made every effort to give academic credit to those students quitting the University in the middle of the school year, making it easier for them to depart and later return to their studies. The deans of the undergraduate schools asked each professor to judge what might have been the grade of an enlisted student had he stayed until the end of the term. In this manner, academic credit was given where possible.

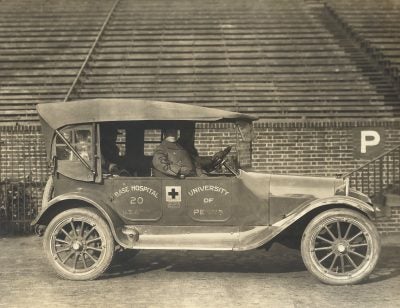

Penn made a particularly great and immediate contribution to the United States in the area of medical service. Soon after the war began, Base Hospital #20, whose chief medical officers were made up entirely of men from the Penn Medical School and the University’s hospital, set off for France. Many of the 153 general staff members of the hospital were Penn medical students. The University also contributed three Ambulance Units and several Red Cross Units. Courses for undergraduates studying medicine or nursing were expedited so that more men and women could be sent overseas in a shorter amount of time. For example, the nursing course, usually a full three years, was reduced to a three month course in 1917 for those women who wanted to serve the Government without waiting. Meanwhile, the medical and dental schools emphasized courses that would prepare students to administer treatment for heavy combat injuries. The dental school focused on oral and plastic surgery, while the medical school taught operative surgery on the cadaver and neurological diagnosis, which would help medical officers to assess trauma and shock cases.

For those students whose studies did not relate so immediately and directly to the war effort, the University created new courses to accommodate the needs of the Government. A local Philadelphia newspaper took note of these drastic changes at the University:

The curriculum of not a single department remains unchanged where the least possible assistance can be rendered to the Government. In the laboratory and the classroom war service is the dominant aim, and a virtual upheaval has been caused in long-honored traditions of study in this adaptation to the new conditions.

Among the first of these new courses was a course in navigation, around which an entire Navigation School was created. The Navigation School opened its first session on July 8th, 1917, only three months after the United States joined the war. Penn faculty members taught students not only about the practical skills of sailing the oceans, but also about maritime law, marine engineering, and shipping and admiralty. The Towne Scientific School introduced special courses that would be of use to the Government’s communication systems. As early as January, 1916, the Government asked the Towne School to focus on special work to fit the needs of the Signal Corps. In March of 1918, Dr. Pender, Penn Professor of Electrical Engineering, sought approval from the Towne faculty for a temporary change in the curriculum for seniors in the Electrical Engineering program, so that important work could be done for the Government in Radio Communication. In addition, The Wharton School ran a Stores Course with the intention of supplying men to the Ordnance Department of the United States Army. There were even changes in the study of the humanities. The College began to offer more German classes, as well as courses on recent European history and recent American-European relations. These courses would be helpful for understanding the diplomatic relationships that existed during the Great War, and would make easier communication with the Allies over waging war and also over later peace negotiations. With so many courses geared toward war knowledge, many Penn students became qualified in a variety of areas of skilled Government service. Thus, the University encouraged those students to serve in the department in which they would be most useful to the Government and the war effort, rather than letting their skills go to waste in the trenches. Dean McClellan’s Intercollegiate Intelligence Bureau remained active in helping to achieve this goal.

The war-time atmosphere at the University extended beyond the academic realm; there was also a great emphasis on the role of physical activity in the war effort:

It was deemed best at Pennsylvania last spring upon the outbreak of the war to endeavor to use the athletic organization outlined above to fit the requirements of any new conditions which might be presented… When the students arrived at the University in the fall [of 1917] instead of being met with a number of individual appeals from different sports to turn out, they found the Campus placarded with large posters which set forth their duty to their country to keep in the very best physical condition…

R. Tait McKenzie, head of the Department of Physical Education, stressed the importance of training men to be physically fit before they were called to active duty as soldiers. He required that all undergraduate students take at least two periods a week of Physical Education, and he ensured that the University’s physical education program would provide the exercises necessary for making every student prepared for the possibility of service:

McKenzie also wrote lectures on various topics concerning physical fitness in the context of the military, such as the construction of boots, marching, physical training, the medical examination of the recruit, and organization of convalescent camps. On October 30th, 1917, George Nitzsche, Recorder of the University, along with Medical Corps officers and R. Tait McKenzie, took pictures of the motion of athletes in order to show the correct way to do military exercises, and the injuries that could result from doing them incorrectly. In this way, the University contributed greatly to the physical training of soldiers and to military medical care and rehabilitation. In January of 1918, the military focus of the physical education and athletic programs increased: The military course was deemed mandatory for all members of varsity athletic teams. A month later, R. Tait McKenzie and Major Charles T. Griffith of the United States Army created a new course in military athletics, which would be a supplement to military training. In addition to enacting a myriad of wartime changes, the University invited the United States Government to play an extensive role in directing the campus’ war effort. Provost Smith and the University administration gave the War Department permission to use Penn facilities when needed, as well as to lead military instruction at the University. At the very beginning of the war, the Board of Trustees gave priority for use of the gymnasium and of Franklin Field to students drilling under Major Kelly. Major Kelly also directed the Department of Military Science and Tactics, in which students could take classes such as International Relations of America from Discovery to Present Day, Gradual Growth of Principles of International Law in American Diplomacy, Legislation, and Psychology of War. On June 10, 1918, Provost Smith, with the approval of the special Committee on Military Training, proposed to the Board of Trustees a plan for a full four-year course in Military Science. The course would be guided by Major Charles T. Griffith of the United States Army, who had succeeded Major Kelly as Professor of Military Science and Tactics, and would result in the degree of B.S. in Military Science. The Board approved the Provost’s plan. At the same meeting, the Committee on Finance and Property announced that a certain amount of dormitory space had been turned over by the University to the Navy. The committee seemingly expected the Government to utilize more space, as it stated that any other “tenants of National character” would be referred to the Provost and Chairman for consideration. With access to Penn’s living quarters, as well as laboratory equipment and space, the Government was able to train thousands of men from all over the country at the University of Pennsylvania:At the University of Pennsylvania we have at least 3000 students who have been taking the required work in physical education all the way from one to four years and who are now ready and fit to go at once into active training necessary to the soldier…

It is thus seen that several thousand men, besides the regular University of Pennsylvania students, are now being trained annually at the University for special branches of the United States service.

The greatest contribution, however, that the Government made to the war effort at the University was in directing the military training of Penn students who joined first the Student Battalion, then the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C.), and finally the Students’ Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.). The Student Battalion, created in 1916 for those students who voluntarily enrolled in the Military Science and Tactics course, had become one of the largest student battalions in the United States by the fall of 1917, with around 2,300 men. Men in the Student Battalion drilled outside the dormitories, on the football field, and on occasion marched in parades on the campus. For this reason the military seemed to be omnipresent at the University from the very beginning of United States participation in the war. Even non-military student organizations contributed to the growth of military life; for example, Mask and Wig, a prominent theater group at the University, voted to donate the proceeds from its spring 1917 show to the military efforts at Penn. Still, military life would only prove to increase its influence as the war continued.

In order to improve the productivity of military training, the University set aside the hour from 3:30 PM to 4:30 PM for military training five days a week. Those not involved in the military training course would be barred from Franklin Field during that hour. In addition, early in 1918 the University began making arrangements for the creation of a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, one unit for Infantry and one for Engineers. Success in these arrangements would result in a more formal commitment to the goal of training reserve officers, which had been set out by the War Department in its outline of the University’s first military training course in 1916. In February the War Department authorized the University to establish an Infantry Unit of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, and on February 11, 1918, close to 1,000 students took the oath of enlistment into this new cadet organization. The oath was written by the Professor of Military Science and Tactics, Major Charles T. Griffith, and approved by the Provost and the University’s Committee on Military Affairs. The students who enlisted agreed “to take the course of Military Training prescribed by the War Department for Infantry Units of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps…” This marked the official beginning of the R.O.T.C. at Penn, directed by Major Griffith. Upon successful completion of the R.O.T.C. course, students earned commissions as second lieutenants in the Officers’ Reserve Corps, or could be deemed eligible for immediate service in the army. Students who did not want to join the R.O.T.C. could still enroll in the military training course, but would lose the benefit of a Reserve Officer’s commission. The R.O.T.C. would later become the longest lasting outgrowth of the World War I era at the University. Nonetheless, the Students’ Army Training Corps, established by the Government in the fall of 1918, would be the final and most intense phase of military training at Penn during World War I.

The intensification of the war in the summer of 1918 led the Government to believe that it might have to ultimately draft a great majority of college men in order to maintain the necessary war effort. The Government’s sense of urgency echoed across the University of Pennsylvania in the fall of 1918, as the University administration permitted an even larger Government presence on campus than what already existed. At the Board of Trustees Meeting on September 9, 1918, Provost Smith

Outlined the student courses which it is proposed to conduct at the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of the United States Government and asked the authority of the Board to enter into a temporary contract with the War Department for the purposes indicated.

The Board approved the courses and granted the desired authorization to the Provost. Within a month the Government established the Students’ Army Training Corps and the Naval Training Unit at the University under the contract between the school and the War Department, and reached the height of its control of the Penn war effort. Those students who chose to make the commitment to the S.A.T.C. were inducted on October 1, 1918 at the University. Members were considered to be part of the United States Army. Military life now eclipsed the student life that had previously existed at Penn. Students of the S.A.T.C. lived on a military schedule and in military housing, ate in military-style mess halls, and participated in drill and athletics every single day:

The student, by voluntary induction, became a soldier in the United States Army, uniformed, subject to military discipline and with the pay of a private. They were simultaneously placed on full active duty and contracts were made with the colleges for the housing, subsistence and instruction of the student soldiers. Officers, uniforms, rifles and such other equipment so far as available, were furnished by the War Department. The student-soldiers were given military instruction under officers of the Army, and kept under observation and test to determine their qualification as officer-candidates, and technical experts, such as engineers, chemists and doctors.

The Government also introduced a new curriculum for the members of the S.A.T.C. The War Department’s Committee on Education and Special Training had the sole authority to approve courses for the Students’ Army Training Corps, though professors and administrators at the University were able to suggest courses. The University developed a Curriculum Committee to outline a recommended four year course of study for students involved in military training. Many of the courses approved by the War Department were directly related to the war. For example, the War Issues course, taught by Dr. William E. Lingelbach of the University of Pennsylvania, was prescribed for all students in the S.A.T.C. Other courses included War Aims, Military or Naval Law, International Law, and Hygiene and Sanitation. In addition, the War Department required that monthly grade reports be submitted by the University professors on behalf of each student in the Training Corps. The Government controlled when students could transfer classes, and when they could drop classes, even if a professor disagreed with the decision made. Although the University faculty and administration were supposed to remain in charge of all academic functions of the University, the Government effectively took total control of the lives of students in military training.

Even students who chose not to join the Students’ Army Training Corps were affected directly by its existence at the University. While the S.A.T.C. operated, regular student activities, such as fraternity life and student publications, were effectively suspended. Athletic teams no longer represented Penn, but instead represented the S.A.T.C. at Penn. Rather than Pennsylvania Football and Pennsylvania Basketball, there was the S.A.T.C. Football Team, and the S.A.T.C. Basketball Team. Military training and athletics at the University had already developed close ties during the war, but now the entire athletic organization was overtaken by the military. The Students’ Army Training Corps did not last long, as it would be demobilized shortly after the signing of the armistice in November of 1918, but during its short existence its presence was certainly all-consuming.

Pro-War Sentiments

The many changes that the University experienced during wartime brought the war very close to home for the Penn community. The University’s patriotic atmosphere relied not only on what its members were doing, but also on what they were saying about the war. Patriotic speeches, articles, and lectures permeated the campus, and reinforced the sense of duty that existed.

Provost Smith was particularly enthusiastic about the war effort, despite its inevitable effect on enrollments at the University. The University was projected to lose a large amount of revenue due to the absence of its students, and yet the Provost still encouraged students to enlist. Speaking at chapel exercises in April of 1916, Provost Smith urged all undergraduates to join the Student Battalion directed by Major Kelly. He spoke about the great sacrifices that Penn men had made in all wars prior to the Great War, and expected that the sons of Pennsylvania would again rise to the call of their country. Furthermore, he praised those men who enlisted, reassuring them that they were making a noble choice:

It is fitting…that we should give generously in the present war. If I were a young man I would enlist for service just as you young men are doing. The country needs us all.

In addition to demonstrating his own patriotism, Provost Smith invited speakers to the University who similarly addressed the themes of duty and service. The Archbishop of York, who visited the University on March 26, 1918, was one such speaker. Having witnessed the incredible sacrifices made by English college students, he solemnly declared that a man is happier when serving a greater cause, and that the University should be prepared to make the sacrifices necessary to fight for that greater cause:

I am sure Mr. Provost that in response to the call of this great time you are ready to make the sacrifice, your students are ready to make the sacrifice, for the sake of the university and the country, and I know you are ready after this war is over to raise the whole tone of the life of the university to a higher power, to that great and inspiring and exhilarating thought that the University of Pennsylvania will make the answer “I am ready.”

The Archbishop also commended the country for taking up the fight for liberty with such strength:

I rejoice with you here in America that every section, that every class is beginning to realize the cause which is being brought to the whole nation, the understanding that the world will get liberty and power just in proportion as it strives for them.

In this way the sense of duty to serve was made almost inescapable at the University.

Many students took the encouragement to serve to heart, and wrote articles attempting to persuade the University and fellow students to expand their focus on the war. Some students expressed the opinion that all studies unrelated to the war effort were a waste of time. They felt that they ought to be preparing for war on a full time basis, and that regular academic studies had no purpose in that endeavor. In fact, some students threatened not to return to the University if they could not find satisfactory war training there:

Is Pennsylvania on a war-time basis? Is she giving her sons the kind of training that seems of immediate value to them? We think not, and take the stand that the University should do as others have done – cut out some of the courses that are purely cultural or purely theoretical and have no immediate bearing on the WAR. We hear fellows complaining every day that they feel they are wasting their time at college…that they would like to have courses that would fit them for some capacity in the service… We think it would tend to bring a large number of men to Pennsylvania next year who would not otherwise come, thinking the regular college course would be of no benefit to them under war conditions.

One student, Ernest L. Noon, wrote in the Red and Blue, a student publication, that pursuing a college education was not an excuse to avoid service to the Government. Although the importance of education and specialized knowledge was being emphasized by the Government and organizations like the Intercollegiate Intelligence Bureau, this student did not believe that remaining at the University was a valid form of war service. Noon believed that college men were the best source of soldiers for the front, since taking them would not interrupt any domestic industry that could be important to the war effort. He questioned, therefore, why students were still allowed to remain in school, rather than at the front:

Clearly we are the men wanted. Why, then, are we allowed to stay?…. We are allowed to stay in college, because here we can make ourselves more valuable to our government than if we were at the front…. But the advisability of remaining in college has been so dinned into our ears that we have come to believe the action laudatory in itself. We have actually talked ourselves into believing that merely because we are at college instead of at the front we are sterling patriots, all.

Similar to Noon, other students urged more of their peers to join in military training at the University, citing both personal benefits and benefits to the national cause as reasons to join.

For other members of the Penn community, patriotism ran deeper than unquestioning loyalty to their country; for these individuals the ideals that the United States was fighting to protect were a large part of the reason that they supported the war effort. James C. Ballagh, professor of Political Science at the University, gave a free lecture about these ideals during the 1917-1918 school year. He spoke of the American obligation to protect liberty and international law around the globe, and the great work the United States was doing to achieve this goal by participating in the Great War:

Never before, in the history of the world has such a thing been attempted, has a government and a nation put its whole vital force and energy behind the establishment of such a world ideal. Never before has the United States risen to such a high conception of its international obligations and opportunities for true political altruism.

Ballagh strongly supported President Wilson’s plan for a League of Nations, which would promote universal peace through internationalism, and he believed that the United States would lead in implementing Wilson’s doctrine. Echoing Ballagh’s sentiment, a student of the class of 1919 explained in an article in the Red and Blue magazine that the ideals espoused by President Wilson persuaded him to support the war, even though he had originally been against it:

We are not fighting for glory, or lands, or power, or our lives, but for an ideal, for the ideal of democracy and for world peace and development through democracy.

Both Professor Ballagh and this student author reflect the beginning of a change in opinion on the United States’ position in the global sphere. A portion of the American population, spearheaded by President Wilson, believed not only that the United States should become more involved in global politics, but that it had the obligation to defend the principles of liberty and justice all over the world. Those who subscribed to this belief effectively redefined American interests to include ensuring the survival of American ideals around the world. Thus, any threat to democracy on the globe would be a threat to the United States and its way of life. This belief implied that, rather than isolating itself from foreign conflict, the United States would have a purpose for joining future conflicts akin to World War I. It was, however, by no means a universal belief. Throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, the idea of the United States as the global protector of democracy has been hotly debated, and tested in conflicts such as the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the war in Iraq. But the roots of the debate took hold during the Great War.

Those Who Went and Those Who Stayed: Pennsylvania’s Support for All Her Sons

In the midst of the patriotic frenzy at the University, many students did leave to fight overseas. The Penn community made a great effort to keep in touch with those students, and to send mementos of the University to show support. In 1917, for example, the University sent care packages to all soldiers during Christmas, which included a greeting from the Provost. In addition, periodicals such as Old Penn and Red and Blue attempted to sell subscriptions on behalf of soldiers and send those soldiers their magazines overseas to provide some source of enjoyment during the war. Red and Blue eventually published letters from soldiers to students still at the University so that all students could be aware of the lives of their classmates at the front. Furthermore, when wounded soldiers began to return to the University, student fraternities agreed to entertain them, doing a service for their fellow Penn students.

There were many more instances of respect and support for those students who went overseas, including speeches and the erection of memorials honoring soldiers. But Provost Smith in particular made it very clear that he also respected and supported those men who remained in school at the University during the war. The Provost was outspoken in his encouragement for students to enlist, but simultaneously he implored students to realize how important a college education was to the war effort. When the war broke out in April of 1917, there were rumors that the University would cease normal operation in the fall of the following year. The Provost, however, would not allow this to occur; he opened the doors of the University as usual in the fall of 1917, and vigorously combated the idea that academic work was unimportant during the national emergency. Noting the terrible losses in college-aged men that England had already suffered, as well as the scientific advances that made the Great War deadlier than any previous conflict in history, Provost Smith stated,

This war itself is a scientific war; and before it ends we shall need, as the other nations have already found, to continue unremittingly at the task of research and preparation. That task, though not so sensationally obvious, is as indispensable and as honorable as the tasks of agriculture and manufactures… Let each student who has decided to devote himself to military service make every effort that his vacant place in the army of science and learning shall be filled during the coming year by at least one other enlistment in college or professional school.

Several students seemed to think that any education not pertaining to the war was a waste of time, but the Provost had the foresight to see that expertise in specialized academic knowledge was necessary not only for the war effort, but also for leading the country in the post-war period. England lost a generation of bright minds to the trenches, but the Provost was determined to save as many bright minds as possible for the future of the country.

Provost Smith was not alone in thinking that the preservation of higher education was important. While reporting on behalf of the Committee on Graduate and Law Schools, Dean Ames of the Graduate School expressed to the Board of Trustees his hope that, “in case of retrenchment in expenses for instruction, due to the exigencies of the war situation, care would be taken not to curtail the instruction in the Graduate School.” Dean Ames thought it important to maintain the University’s usual level of academic instruction, as the Provost was determined to do. In addition to administrators, some younger members of the Penn community also emphasized the power of a college degree. Dr. William Seal Carpenter, who graduated from the University before the war began, wrote an article for Red and Blue on how the war was affecting the University. Carpenter believed the war effort was important, but should not become the University’s only purpose:

But it would be calamitous if, in the preparation for war, the college should lose sight of its larger function. It must be more than a mere training school for Government work. Intellectual leadership will be needed in the days of peace which are to come. To train men to think still remains the task set for the college.

In this way, Carpenter agreed with the sentiments expressed by Dr. Cheyney before the United States joined the war: the most important skill the University could teach its students, both for their benefit and for the country’s, was that of independent thinking, a skill that war preparation alone simply could not provide.