Eager to create a college to educate future generations of Philadelphians, Benjamin Franklin presented to the men and women of Philadelphia in the fall of 1749 his vision of a school to be known as the “Publick Academy of Philadelphia.” Circulating his ideas in a pamphlet titled Proposals for the Education of Youth in Pensilvania, he advocated an innovative concept of higher education, one which simultaneously taught both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living. The four colleges then in existence in the English colonies — Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, and Princeton — were all schools for educating the clergy, rather than preparing their students for lives of business and public service. With his characteristic zeal and intent on seeing his Academy of Philadelphia become a reality, he assembled a board of trustees and looked about for the least costly way to build a campus.

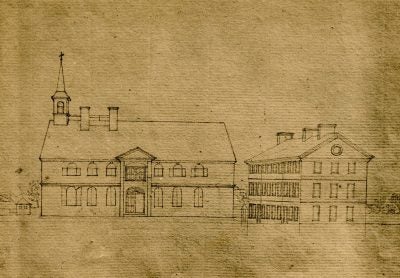

Although one of the trustees offered a well-situated building lot, Franklin focused on the property and unfinished “New Building” of the evangelist George Whitefield. There, in 1740, a group of working class Philadelphians had decided to erect a great preaching hall, the largest building in the city, which would also serve as a charity school for “the instruction of poor children.” The fundraising, however, for both the building and the school had fallen short and the plans for both chapel and school were suspended. Franklin saw an opportunity to open his Academy quickly and inexpensively and in January 1751 did so, incorporating and also opening a charity school in accordance with the intentions of the original “New Building” donors.

Franklin’s hand-picked Provost, the Reverend William Smith, cast just as powerful and as lasting a shadow on both Penn and on the American University as Franklin did. Smith designed a curriculum to imbue the students with both the Classics and the more pragmatic sciences — again a unique development among the Colonial Colleges. Smith had such a dedication to the school that, when he was thrown in jail for protesting against the politics of the popularly-elected Provincial Assembly, he continued to teach his classes from the Old City Jail!

Amidst the turmoil of the American Revolution a few years later, the state of Pennsylvania seized the College of Philadelphia in 1779 because the revolutionary Pennsylvania state government saw the College as a Tory bastion. The state transformed the College into the University of the State of Pennsylvania, thus creating both America’s first state school and America’s first university. This new university was born with a more egalitarian vision than ever imagined before in the colonies, with members of the Board of Trustees from every denomination and the only non-sectarian faculty in the new nation. The University of Pennsylvania earned its current name when the University was made private, once the revolutionary fervor had died down, in 1791.

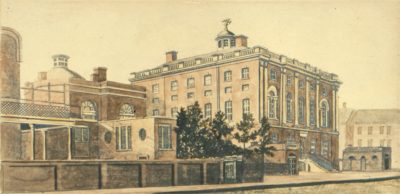

The eighteenth century was an incredible time for both the University and for the young American Republic. The University saw rise to the first Medical School in the colonies in 1765 when John Morgan organized a medical faculty. James Wilson gave the earliest law lectures under the new national government in 1790 at Penn. By the end of its first half century, the University had been educating the leadership of Penn and of the new nation: nine signers of the Declaration of Independence and eleven signers of the Constitution were associated with the University. Having been home to the Continental Congress in College Hall 1778, the University moved to the President’s House on Ninth and Chestnut Streets in 1802.

After almost a century and a half as a teaching college, the University — with a student body that by the end of the 19th century was still publicly performing Aristophanes’s plays together — began to change with the times. Influenced by the German model of higher education, Penn magnificently transformed itself into a research institution — not only transmitting knowledge, but now creating it as well. Under the leadership of Provost Charles Janeway Stillé in 1872, Penn relocated its campus a second time, to the sprawling Almshouse farm west of Philadelphia’s Schulykill River, where it remains today. Here Franklin’s spirit of discovery and invention was reborn, with blocks of labs along Spruce Street popping up and countless researchers being hired. Focusing on research and the advancement of knowledge, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences was founded at Penn in 1882 and the first Ph.D., in Physics, was awarded in 1889, both under the provostship of William Pepper.

The University, while transforming itself into a modern research institution, developed a number of professional schools. Founded in 1850 and 1852, respectively, today’s Law School and the School of Engineering and Applied Science led the nation in the move towards professional education. Four others — Dentistry, 1878; Wharton’s School of Finance and Commerce, 1881; Veterinary Medicine, 1884; and Fine Arts, 1890 — were born into this educational age of great laboratories and clinical research. Penn, too, entered modernity and embraced the diversity of America during this period, as it admitted its first students of color in 1879. Women were admitted to the graduate school from its inception in 1882, and belatedly the undergraduate programs as well, starting with the establishment of the School of Education in 1914.

A second transformation of sorts took place at Penn after 1940, resulting in the University of today. During the Second World War, massive infusions of federal dollars made it possible for Penn to be a major contributor to the war effort. Immediately afterwards, the G.I. Bill paid for thousands more to attend the University. The size of Penn exploded after a national peacetime consensus developed during the 1950s and 1960s to use tax dollars to support basic research and University-based training. The University, which had graduated 301 students in 1890, graduated 5,634 in 1990. With an enormous range of research grants available and highly-specialized faculty now competing for federal, state, and local grant money, the University became today’s booming Penn, the one which created ENIAC, the world’s first all-electronic computer.

The mission of the University has changed in still another important way since the War, a change which has invoked the vision of its eighteenth century founders. Since 1945, the curriculum has steadily broadened to include virtually every significant academic discipline and this great arena of learning has opened to tens of thousands of women, minorities, and international students through need-blind admissions and enrollment. Penn has therefore accomplished something even far beyond the ideals of Franklin and Smith; not only is Penn a world center for the creation and transmission of knowledge, but now, two centuries after its founders advanced the twin ideas of pragmatism and inclusiveness in American higher education, that vision has been universally embraced by research colleges and universities throughout the United States.