With the passage of time, once celebrated wartime services of the University tend to become ever diminishing memories. As Penn’s institutional memory of World War II is now vested solely in “Old Guard” alumni and alumnae, emeriti faculty, and retired staff, an account of the University’s 20th General Hospital should be made available to alumni and alumnae for comment. At the outset, however, it should be noted that World War II’s 20th General Hospital had a World War I predecessor, a U.S. Army Medical Corps unit with a very similar name — Base Hospital No. 20 — but one which operated on the opposite side of the world. The account which follows below begins in 1916, continues to 1919, and then leapfrogs to 1940, when preparations first begin for World War II.

World War I: Base Hospital No. 20

Responding to the likelihood of American entry into World War I, the University of Pennsylvania, in conjunction with the American Red Cross and the War Department, organized the civilian Base Hospital No. 20 in 1916. When Congress declared war against Germany in April 1917, the University appointed John B. Carnett, M.D., an Associate in Surgery at the School of Medicine, Director of the Base Hospital. Carnett selected George M. Piersol, M.D., an Associate in Medicine, as Chief of the Hospital’s Medical Service and Eldridge L. Eliason, M.D., an Instructor in Surgery, as Chief of Surgical Service. As Hospital dentists, Carnett selected two Instructors from the faculty of the School of Dentistry, Frank P.K. Barker, D.D.S., and John S. Owens, D.D.S. As Chief Nurse of the Hospital, Carnett selected the Chief Nurse of HUP’s General Surgical Clinic, Edith B. Irwin, HUP class of 1912.

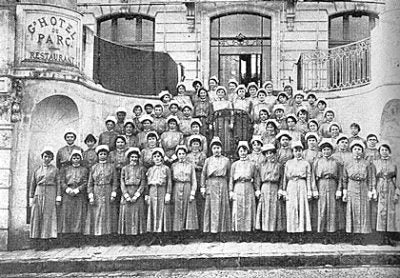

With a core of Penn-affiliated senior officers, it is not surprising that the Base Hospital staff of twenty-two medical officers, two dentists, one chaplain, sixty-five nurses and one hundred and fifty-three enlisted men were largely Penn faculty, health care professionals, students, and alumni. University Trustees, a newly-formed Women’s Auxiliary of the Red Cross, and other benefactors donated more than thirty-six thousand dollars to train and equip the Base staff. The University granted the use of Weightman Hall, the White House, and Franklin Field for training purposes. In late November the War Department called Base Hospital No. 20 into active service in the Medical Corps of the United States Army.

Five months later the unit sailed for France, finally arriving on May 7, 1918 in Chatel Guyon, Puy de Dome, midway between Paris and Marseilles. For the next eight months until its closure in January 1919, Base Hospital No. 20 operated out of hotels in this health resort, eventually reaching a capacity of 2,500 beds in thirty-three buildings.

Although most of the patients were Americans, there were also a few French soldiers as well as some German prisoners. Approximately 4,000 surgical cases and 3,500 medical and gas patients were treated as well as 1,500 others, with only sixty-five deaths. The hospital treated battle casualties and disease, but was also known for its role as an observation hospital for tuberculosis patients and for its unusual success in dealing with the influenza epidemic.

Suspension and Carrel-Dakin Treatment of Infected Fracture Photo from History of United States Army Base Hospital No. 20, p. 51 |

World War II: 20th General Hospital

During the Second World War, Penn was again called upon to organize a military hospital overseas and again provided outstanding war-time medical service. Compared to the University’s World War I base hospital, the 20th General Hospital of World War II would serve eight times as many patients with double the number of staff over a significantly longer time frame and in a very different part of the world.

The organization of the 20th General Hospital began as early as 1940 at the invitation of the U.S. Surgeon-General. A Penn medical faculty committee asked Dr. Thomas Fitz-Hugh, Jr., Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, to become Chief of Medical Service and Dr. Isidor S. Ravdin, Professor of Surgery, to serve as both Executive Officer and Chief of the Surgical Service (in 1945 he became Commanding Officer). Mary Cornelius and Vera F. Shaw headed up the Hospital Nursing Staff. As in World War I, most of the Hospital’s staff (59 medical, surgical, laboratory and dental specialists, 120 nurses and approximately 600 enlisted men) had ties with the University, particularly the hospital and medical school.

The Hospital’s preliminary preparations–meetings, committee work, the commissioning and training of staff–took place in Philadelphia during the next two years. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Hospital was already well-organized. The unit entered active service on May 15, 1942, with a large and enthusiastic send-off from the crowd at 30th Street Station.

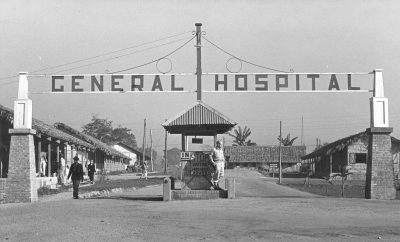

After almost eight months of training at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, the unit journeyed via California, New Zealand and Australia, finally arriving on March 21at Ledo, a former tiny railroad bazaar surrounded by the virgin jungle on the fringe of the tea plantations in the Assam region of northeast India. The mountainous border with China was to the north and Burma (today also known locally as “Myanmar”) lay on the east. At this time the Japanese invasion of China had forced the Chinese government into the interior, with Burma offering the only possible route of land communication between the Chinese and the Allies. To reopen communications with the Chinese, General Stilwell chose Ledo as the western terminus of his road into North Burma, to be built with the engineering and organizational skills of General Lewis A. Pick. As a huge military installation sprung up at Ledo, the 20th General Hospital took on the mission of providing medical care for the American-Chinese forces fighting the Japanese in Burma as well as for men constructing the Ledo road.

Ravdin’s first impressions were not exactly favorable. He wrote:

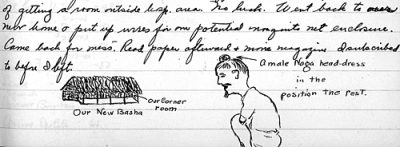

“The first view of the hospital was something never to be forgotten. We splashed out of the trucks into nearly six (6) inches of soft slippery mud. It was a raw day, with leaden clouds and a driving rain. The hospital was being run by the 98th Station Hospital Staff. It consisted of a large polo field, on which were no buildings because it was said to be covered with water during the monsoon.”

The bamboo “bashas” of Ledo were very different indeed from the hotels of Chatel Guyon. Constructed on higher ground around a former polo field, these native structures housed the hospital and its patients, nurses, doctors, and enlisted men. These bashas had dirt floors, sometimes covered with bamboo matting, and leaky roofs of palm leaves. There were no lights and very few outlets for water. In this area of heavy rainfall, malaria and bacillary and amoebic dysentery were constant; leeches and mites presented even more dangers than the snakes, tigers, elephants, bears, bison and rhinoceroses. In India, Penn’s doctors had to deal with battle casualties in an environment that not only made medical treatment difficult, but actually added to the problems.

Ravdin referred to the 20th General Hospital as a “league of nations” hospital since it provided care to American soldiers, to British troops with serious head, chest, and abdominal injuries, and to the Chinese. In fact over half the patients were Chinese soldiers treated for the first time by modern Western medicine; they occupied an entire, separate section of the hospital grounds.

The achievements of Ravdin and the Penn medical team were remarkable. There were high profile stories, such as Major Harold Scheie’s treatment of Lord Louis Montbatten after his eyeball was pierced during an inspection tour in North Burma. Scheie, who had been an Associate Professor of Ophthalmology in the Medical School would return to Penn after the war, becoming in 1972 the Founding Director of the Scheie Eye Institute.

But such stories were only part of a very impressive war-time medical contribution. The Hospital ultimately occupied 289 buildings and 162 tents, and admitted 73,000 patients. Even dealing with battle casualties, scrub typhus, cerebral malaria and other challenges, the overall mortality rate was only 0.4 per cent–no worse than for civilian hospitals. Ravdin was proud that his staff was able to use modern practices including antibiotics, innovations such as air-conditioning, and the application of sound surgical principles, to demonstrate that the surgery of war can be done with as much care and success as civilian surgery.

The World War II experiences of the 20th General Hospital had a lasting effect not just on those who served in the jungles of Assam, but also on the University and the City of Philadelphia. Ravdin and his colleagues returned to a heroes’ welcome at the end of the war. Not only did they maintain their war-time bonds through a number of reunions in subsequent years, but many, like Ravdin, provided important leadership to the University and the City of Philadelphia through the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Sources

The University Archives has a number of records telling the story of Base Hospital No. 20 during World War I. For more information, consult the following:

- U.S. Army Base Hospital #20 Papers, inventory (UPC 14)

- William Gilmore Leaman, Jr. Photograph Album (UPX L436)

- Pennsylvania Gazette (UPM 8125), 1917 through 1919, particularly a May 9, 1919 article “Remarkable Record of Base Hospital No. 20”.

- History of United States Army Base Hospital No. 20 Organized at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: 1920). (UPP 71)

The 20th General Hospital during World War II has even more documentation in the University Archives. For manuscript collections consult:

- Guide to the I. S. Ravdin Collection. (UPT 50/R252)

- Guide to the Harold Glendon Scheie, M.D., 1909-1990, Papers. (UPT 50/S318)

- Inventory of the U.S. Army 20th General Hospital, World War II Papers (UPC 15) which includes:

- Roster of Penn’s 20th General Hospital at the time it left Camp Claiborne

Printed sources include:

- Articles in the Pennsylvania Gazette during World War II and later, including “20th Hospital Unit Holds Reunion” (June, 1950). (UPM 8125))

- Report of the 20th General Hospital, 3 April 1943 – 1 August 1945 by Brig. Gen. I. S. Ravdin to The Surgeon General is a bound photocopied volume (made in July 1959) of Ravdin’s extensive history of the Hospital as found in manuscript form in the I.S. Ravdin Collection. (UPI 491.10)