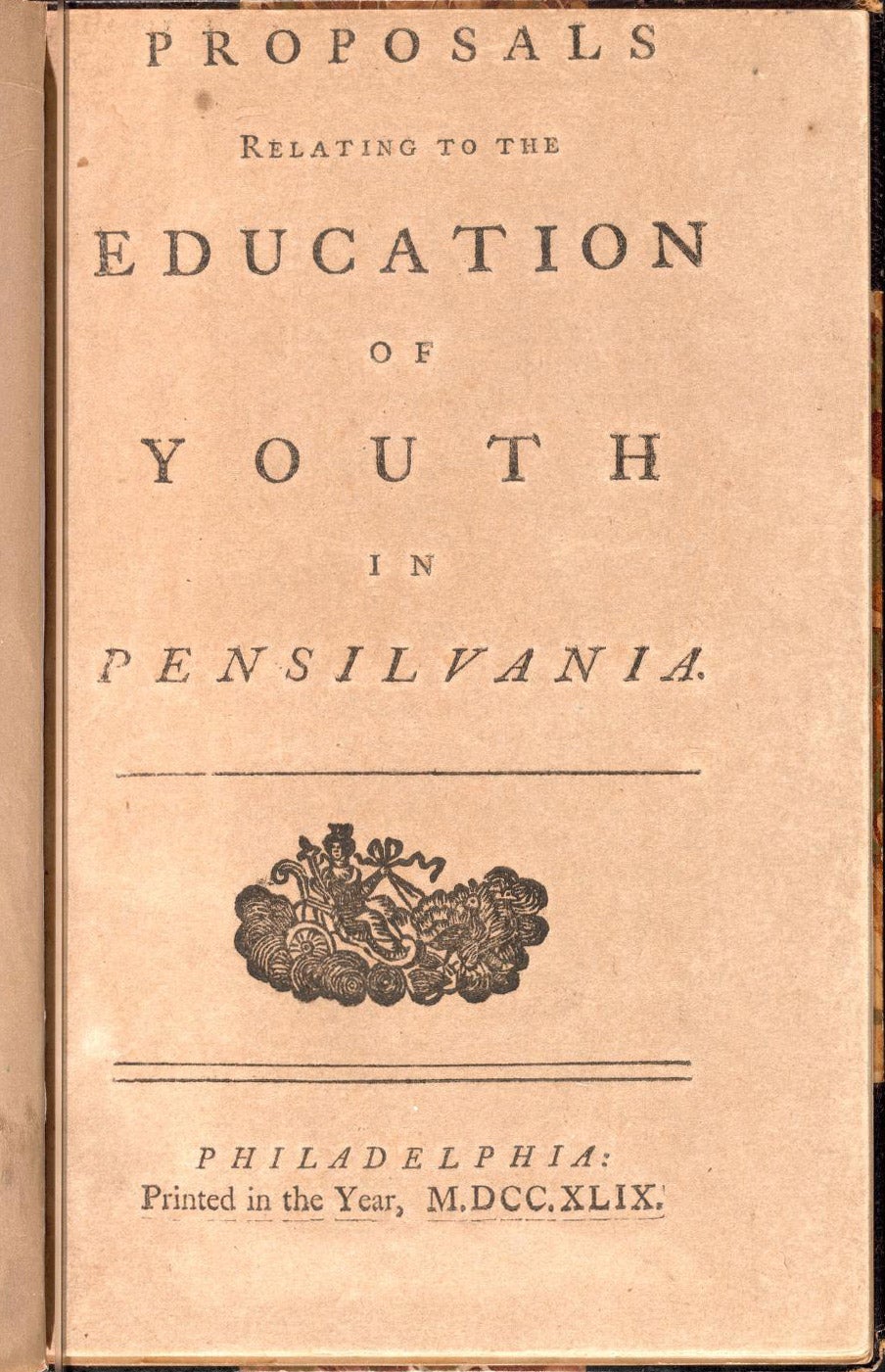

Note from the University Archives and Records Center: Benjamin Franklin’s 1749 pamphlet on the aims of education, Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania, led directly to the founding of the Academy of Philadelphia, since 1791 known as the University of Pennsylvania. This html version was created by Derek Smith, C’97.

[View facsimile of the original in its entirety]

Advertisement to the Reader.

It has long been regretted as a Misfortune to the Youth of this Province, that we have no ACADEMY, in which they might receive the Accomplishments of a regular Education.

The following Paper of Hints towards forming a Plan for that Purpose, is so far approv’d by some publick-spirited Gentlemen, to whom it has been privately communicated, that they have directed a Number of Copies to be made by the Press, and properly distributed, in order to obtain the Sentiments and Advice of Men of Learning, Understanding, and Experience in these Matters; and have determin’d to use their Interest and best Endeavours, to have the Scheme, when compleated, carried gradually into Execution; in which they have Reason to believe they shall have the hearty Concurrence and Assistance of many who are Wellwishers to their Country.

Those who incline to favour the Design with their Advice, either as to the Parts of Learning to be taught, the Order of Study, the Method of Teaching, the Oeconomy of the School, or any other Matter of Importance to the Success of the Undertaking, are desired to communicate their Sentiments as soon as may be, by Letter directed to B. Franklin, Printer, in Philadelphia.

AUTHORS quoted in this PAPER.

1. The famous Milton, whose Learning and Abilities are well known, and who had practised some Time the Education of Youth, so could speak from Experience.

2. The great Mr. Locke, who wrote a Treatise on Education, well known, and much esteemed, being translated into most of the modern Languages of Europe.

3. Dialogues on Education, 2 Vols. Octavo, that are much esteem’d, having had two Editions in 3 Years. Suppos’d to be wrote by the ingenious Mr. Hutcheson (Author of A Treatise on the Passions, and another on the Ideas of Beauty and Virtue) who has had much Experience in Educating of Youth, being a Professor in the College at Glasgow, &c.

4. The learned Mr. Obadiah Walker, who had been many Years a Tutor to young Noblemen, and wrote a Treatise on the Education of a young Gentleman; of which the Fifth Edition was printed 1687.

5. The much admired Mons. Rollin, whose whole Life was spent in a College; and wrote 4 Vols. on Education, under the Title of, The Method of Teaching and Studying the Belles Lettres; which are translated into English, Italian, and most of the modern Languages.

6. The learned and ingenious Dr. George Turnbull, Chaplain to the present Prince of Wales; who has had much Experience in the Educating of Youth, and publish’d a Book, Octavo, intituled, Observations on Liberal Education, in all its Branches, 1742.

With some others.

Proposals, &c.

The good Education of Youth has been esteemed by wise Men in all Ages, as the surest Foundation of the Happiness both of private Families and of Common-wealths. Almost all Governments have therefore made it a principal Object of their Attention, to establish and endow with proper Revenues, such Seminaries of Learning, as might supply the succeeding Age with Men qualified to serve the Publick with Honour to themselves, and to their Country.1

Many of the first Settlers of these Provinces, were Men who had received a good Education in Europe, and to their Wisdom and good Management we owe much of our present Prosperity. But their Hands were full, and they could not do all Things. The present Race are not thought to be generally of equal Ability: For though the American Youth are allow’d not to want Capacity; yet the best Capacities require Cultivation, it being truly with them, as with the best Ground, which unless well tilled and sowed with profitable Seed, produces only ranker Weeds.

That we may obtain the Advantages arising from an Increase of Knowledge, and prevent as much as may be the mischievous Consequences that would attend a general Ignorance among us, the following Hints are offered towards forming a Plan for the Education of the Youth of Pennsylvania, viz.

It is propos’d,

THAT some Persons of Leisure and publick Spirit, apply for a CHARTER, by which they may be incorporated, with Power to erect an ACADEMY for the Education of Youth, to govern the same, provide Masters, make Rules, receive Donations, purchase Lands, &c. and to add to their Number, from Time to Time such other Persons as they shall judge suitable.

That the Members of the Corporation make it their Pleasure, and in some Degree their Business, to visit the Academy often, encourage and2 countenance the Youth, countenance and assist the Masters, and by all Means in their Power advance the Usefulness and Reputation of the Design; that they look on the Students as in some Sort their Children, treat them with Familiarity and Affection, and when they have behav’d well, and gone through their Studies, and are to enter the World, zealously unite, and make all the Interest that can be made to establish them,3 whether in Business, Offices, Marriages, or any other Thing for their Advantage, preferably to all other Persons whatsoever even of equal Merit.

And if Men may, and frequently do, catch such a Taste for cultivating Flowers, Planting, Grafting, Inoculating, and the like, as to despise all other Amusements for their Sake, why may not we expect they should acquire a Relish for that more useful Culture of young Minds. Thompson says,

‘Tis Joy to see the human Blossoms blow,

When infant Reason grows apace, and calls

For the kind Hand of an assiduous Care;

Delightful Task! to rear the tender Thought,

To teach the young Idea how to shoot,

To pour the fresh Instruction o’er the Mind,

To breathe th’ enliv’ning Spirit, and to fix

The generous Purpose in the glowing Breast.

That a House be provided for the ACADEMY, if not in the Town, not many Miles from it; the Situation high and dry, and if it may be, not far from a River, having a Garden, Orchard, Meadow, and a Field or two.

That the House be furnished with a Library (if in the Country, if in the Town, the Town4 Libraries may serve) with Maps of all Countries, Globes, some mathematical Instruments, and Apparatus for Experiments in Natural Philosophy, and for Mechanics; Prints, of all Kinds, Prospects, Buildings, Machines, &c.5

That the RECTOR be a Man of good Understanding, good Morals, diligent and patient, learn’d in the Languages and Sciences, and a correct pure Speaker and Writer of the English Tongue; to have such Tutors under him as shall be necessary.

That the boarding Scholars diet6 together, plainly, temperately, and frugally.

That to keep them in Health, and to strengthen and render active their Bodies, they be frequently7 exercis’d in Running, Leaping, Wrestling, and Swimming8 &c.

That they have peculiar Habits to distinguish them from other Youth, if the Academy be in or near the Town; for this, among other Reasons, that their Behaviour may be the better observed.

As to their STUDIES, it would be well if they could be taught every Thing that is useful, and every Thing that is ornamental: But Art is long, and their Time is short. It is therefore propos’d that they learn those Things that are likely to be most useful and most ornamental. Regard being had to the several Professions for which they are intended.

All should be taught to write a fair Hand, and swift, as that is useful to All. And with it may be learnt something of9 Drawing, by Imitation of Prints, and some of the first Principles of Perspective.

10Arithmetick, Accounts, and some of the first Principles of Geometry and Astronomy.

The11 English Language might be taught by Grammar; in which some of our best Writers, as Tillotson, Addison, Pope, Algernoon Sidney, Cato’s Letters, &c. should be Classicks: The Stiles principally to be cultivated, being the clear and the concise. Reading should also be taught, and pronouncing, properly, distinctly, emphatically; not with an even Tone, which under-does, nor a theatrical, which over-does Nature.

To form their Stile, they should be put on Writing12 Letters to each other, making Abstracts of what they read; or writing the same Things in their own Words; telling or writing Stories lately read, in their own Expressions. All to be revis’d and corrected by the Tutor, who should give his Reasons, explain the Force and Import of Words, &c.

To form their13 Pronunciation, they may be put on making Declamations, repeating Speeches, delivering Orations, &c. The Tutor assisting at the Rehearsals, teaching, advising, correcting their Accent, &c.

But if14 HISTORY be made a constant Part of their Reading, such as the Translations of the Greek and Roman Historians, and the modern Histories of antient Greece and Rome, &c. may not almost all Kinds of useful Knowledge be that Way introduc’d to Advantage, and with Pleasure to the Student? As

GEOGRAPHY, by reading with Maps, and being required to point out the Places where the greatest Actions were done, to give their old and new Names, with the Bounds, Situation, Extent of the Countries concern’d, &c.

CHRONOLOGY, by the Help of Helvicus or some other Writer of the Kind, who will enable them to tell when those Events happened; what Princes were Cotemporaries, what States or famous Men flourish’d about that Time, &c. The several principal Epochas to be first well fix’d in their Memories.

ANTIENT CUSTOMS, religious and civil, being frequently mentioned in History, will give Occasion for explaining them; in which the15 Prints of Medals, Basso Relievo’s, and antient Monuments will greatly assist.

MORALITY,16 by descanting and making continual Observations on the Causes of the Rise or Fall of any Man’s Character, Fortune, Power, &c. mention’d in History; the Advantages of Temperance, Order, Frugality, Industry, Perseverance, &c. &c.17 Indeed the general natural Tendency of Reading good History, must be, to fix in the Minds of Youth deep Impressions of the Beauty and Usefulness of Virtue of all Kinds, Publick Spirit, Fortitude, &c.

History will show the wonderful Effects of ORATORY, in governing, turning and leading great Bodies of Mankind, Armies, Cities, Nations. When the Minds of Youth are struck with Admiration at this,18 then is the Time to give them the Principles of that Art, which they will study with Taste and Application. Then they may be made acquainted with the best Models among the Antients, their Beauties being particularly pointed out to them. Modern Political Oratory being chiefly performed by the Pen and Press, its Advantages over the Antient in some Respects are to be shown; as that its Effects are more extensive, more lasting, &c.

History will also afford frequent Opportunities of showing the Necessity of a Publick Religion , from its Usefulness to the Publick; the Advantage of a Religious Character among private Persons; the Mischiefs of Superstition, &c. and the Excellency of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION above all others antient or modern.19

History will also give Occasion to expatiate on the Advantage of Civil Orders and Constitutions, how Men and their Properties are protected by joining in Societies and establishing Government; their Industry encouraged and rewarded, Arts invented, and Life made more comfortable: The Advantages of Liberty, Mischiefs of Licentiousness, Benefits arising from good Laws and a due Execution of Justice, &c. Thus may the first Principles of sound20 Politicks be fix’d in the Minds of Youth.

On Historical Occasions, Questions of Right and Wrong, Justice and Injustice, will naturally arise, and may be put to Youth, which they may debate in Conversation and in Writing.21 When they ardently desire Victory, for the Sake of the Praise attending it, they will begin to feel the Want, and be sensible of the Use of Logic, or the Art of Reasoning to discover Truth, and of Arguing to defend it, and convince Adversaries. This would be the Time to acquaint them with the Principles of that Art. Grotius, Puffendorff, and some other Writers of the same Kind, may be used on these Occasions to decide their Disputes.22 Publick Disputes warm the Imagination, whet the Industry, and strengthen the natural Abilities.

When Youth are told, that the Great Men whose Lives and Actions they read in History, spoke two of the best Languages that ever were, the most expressive, copious, beautiful; and that the finest Writings, the most correct Compositions, the most perfect Productions of human Wit and Wisdom, are in those Languages, which have endured Ages, and will endure while there are Men; that no Translation can do them Justice, or give the Pleasure found in Reading the Originals; that those Languages contain all Science; that one of them is become almost universal, being the Language of Learned Men in all Countries; that to understand them is a distinguishing Ornament, &c. they may be thereby made desirous of learning those Languages, and their Industry sharpen’d in the Acquisition of them. All intended for Divinity should be taught the Latin and Greek; for Physick, the Latin, Greek and French; for Law, the Latin and French; Merchants, the French, German, and Spanish: And though all should not be compell’d to learn Latin, Greek, or the modern foreign Languages; yet none that have an ardent Desire to learn them should be refused; their English, Arithmetick, and other Studies absolutely necessary, being at the same Time not neglected.

If the new Universal History were also read, it would give a connected Idea of human Affairs, so far as it goes, which should be follow’d by the best modern Histories, particularly of our Mother Country; then of these Colonies; which should be accompanied with Observations on their Rise, Encrease, Use to Great-Britain, Encouragements, Discouragements, &c. the Means to make them flourish, secure their Liberties, &c.

With the History of Men, Times and Nations, should be read at proper Hours or Days, some of the best Histories of Nature,23 which would not only be delightful to Youth, and furnish them with Matter for their Letters, &c. as well as other History; but afterwards of great Use to them, whether they are Merchants, Handicrafts, or Divines; enabling the first the better to understand many Commodities, Drugs, &c. the second to improve his Trade or Handicraft by new Mixtures, Materials, &c. and the last to adorn his Discourses by beautiful Comparisons, and strengthen them by new Proofs of Divine Providence. The Conversation of all will be improved by it, as Occasions frequently occur of making Natural Observations, which are instructive, agreeable, and entertaining in almost all Companies. Natural History will also afford Opportunities of introducing many Observations, relating to the Preservation of Health, which may be afterwards of great Use. Arbuthnot on Air and Aliment, Sanctorius on Perspiration, Lemery on Foods, and some others, may now be read, and a very little Explanation will make them sufficiently intelligible to Youth.

While they are reading Natural History, might not a little Gardening, Planting, Grafting, Inoculating, &c. be taught and practised; and now and then Excursions made to the neighbouring Plantations of the best Farmers, their Methods observ’d and reason’d upon for the Information of Youth. The Improvement of Agriculture being useful to all,24 and Skill in it no Disparagement to any.

The History of Commerce, of the Invention of Arts, Rise of Manufactures, Progress of Trade, Change of its Seats, with the Reasons, Causes, &c. may also be made entertaining to Youth, and will be useful to all. And this, with the Accounts in other History of the prodigious Force and Effect of Engines and Machines used in War, will naturally introduce a Desire to be instructed in25 Mechanicks, and to be inform’d of the Principles of that Art by which weak Men perform such Wonders, Labour is sav’d, Manufactures expedited, &c. &c. This will be the Time to show them Prints of antient and modern Machines, to explain them, to let them be26 copied, and to give Lectures in Mechanical Philosophy.

With the whole should be constantly inculcated and cultivated, that Benignity of Mind,27 which shows itself in searching for and seizing every Opportunity to serve and to oblige; and is the Foundation of what is called GOOD BREEDING; highly useful to the Possessor, and most agreeable to all.28

The Idea of what is true Merit, should also be often presented to Youth, explain’d and impress’d on their Minds, as consisting in an Inclination join’d with an Ability to serve Mankind, one’s Country, Friends and Family; which Ability is (with the Blessing of God) to be acquir’d or greatly encreas’d by true Learning; and should indeed be the great Aim and29 End of all Learning.

Mr. Rollin says (Belles Lett. p. 249. speaking of the Manner of Educating Youth) “Though it be generally a very wise and judicious Rule to avoid all Singularity, and to follow the received Customs, yet I question whether, in the Point we now treat of, this Principle does not admit of some Exception, and whether we ought not to apprehend the Dangers and Inconveniencies of blindly following the Footsteps of those who have gone before us, so as to consult Custom more than Reason, and the governing our Actions rather by what others do, than by what they should do; from whence it often happens, that an Error once established is handed down from Age to Age, and becomes almost a certain Law, from a Notion, that we ought to act like the rest of Mankind, and follow the Example of the greatest Number. But human Nature is not so happy as to have the greatest Number always make the best Choice, and we too frequently observe the contrary.”

2. Rollin, Vol. 2. p. 371. mentions a French Gentleman, Mons. Hersan, who, “at his own Expence, built a School for the Use of poor Children, one of the finest in the Kingdom; and left a Stipend for the Master. That he himself taught them very often, and generally had some of them at his Table. He clothed several of them; and distributed Rewards among them from Time to Time, in order to encourage them to study.”

3. Something seems wanting in America to incite and stimulate Youth to Study. In Europe the Encouragements to Learning are of themselves much greater than can be given here. Whoever distinguishes himself there, in either of the three learned Professions, gains Fame, and often Wealth and Power: A poor Man’s Son has a Chance, if he studies hard, to rise, either in the Law or the Church, to gainful Offices or Benefices; to an extraordinary Pitch of Grandeur; to have a Voice in Parliament, a Seat among the Peers; as a Statesman or first Minister to govern Nations, and even to mix his Blood with Princes.

4. Besides the English Library begun and carried on by Subscription in Philadelphia, we may expect the Benefit of another much more valuable in the Learned Languages, which has been many Years collecting with the greatest Care, by a Gentleman distinguish’d for his universal Knowledge, no less than for his Judgment in Books. It contains many hundred Volumes of the best Authors in the best Editions, among which are the Polyglot Bible, and Castel‘s Lexicon on it, in 8 large Vols. Aldus‘s Septuagint, Apocrypha and New estament, in Greek, and some other Editions of the same; most of the Fathers; almost all the Greek Authors from Homer himself, in divers Editions (and one of them in that of Rome, with Eustathius‘s Commentaries, in 4 Vols.) to near the End of the 4th Century, with divers later, as Photius, Suidas, divers of Byzantine Historians; all the old Mathematicians, as Archimedes, Apollonius, Euclid, Ptolomy‘s Geography and Almagest, with Theon‘s Commentaries and Diophantus, in the whole above 100 Vols. in Greek Folio’s. All the old Roman Classics without Exception, and some of them in several Editions (as all Tully‘s Works in four Editions). All Graevius, Gronovius, Salengre‘s and Poleni‘s Collections of Roman and Greek Antiquities, containing above Five Hundred distinct Discourses in 33 Tomes, with some Hundreds of late Authors in Latin, as Vossius, Lipsius, Grotius, &c. A good Collection of Mathematical Pieces, as Newton in all the three Editions, Wallis, Huygens, Tacquet, Dechales, &c. in near 100 Vols. in all Sizes, with some Orientals, French and Italian Authors, and many more English, &c. A handsome Building above 60 Feet in front, is now erected in this City, at the private Expence of that Gentleman, for the Reception of this Library, where it is soon to be deposited, and remain for the publick Use, with a valuable yearly Income duly to enlarge it; and I have his Permission to mention it as an Encouragement to the propos’d Academy; to which this noble Benefaction will doubtless be of the greatest Advantage, as not only the Students, but even the Masters themselves, may very much improve by it.

5. See in Turnbull, p. 415. the Description of the Furniture of the School called the Instituto at Bologna, procur’d by the Care and Direction of Count Marsigli, and originally at his private Expence.

6. Perhaps it would be best if none of the Scholars were to diet abroad. Milton is of that Opinion (Tractate of Education) for that much Time would else be lost, and many ill Habits got.

7. Milton proposes, that an Hour and Half before Dinner should be allow’d for Exercise, and recommends among other Exercises, the handling of Arms, but perhaps this may not be thought necessary here. Turnbull, p. 318. says, “Corporal Exercise invigorates the Soul as well as the Body; let one be kept closely to Reading, without allowing him any Respite from Thinking, or any Exercise to his Body, and were it possible to preserve long, by such a Method, his Liking to Study and Knowledge, yet we should soon find such an one become no less soft in his Mind than in his outward Man. Both Mind and Body would thus become gradually too relaxed, too much unbraced for the Fatigues and Duties of active Life. Such is the Union between Soul and Body, that the same Exercises which are conducive, when rightly managed, to consolidate or strengthen the former, are likewise equally necessary and fit to produce Courage, Firmness, and manly Vigour, in the latter. For this, and other Reasons, certain hardy Exercises were reckoned by the Antients an essential Part in the Formation of a liberal Character; and ought to have their Place in Schools where Youth are taught the Languages and Sciences.”

8. ‘Tis suppos’d that every Parent would be glad to have their Children skill’d in Swimming, if it might be learnt in a Place chosen for its Safety, and under the Eye of a careful Person. Mr. Locke says, p. 9. in his Treatise of Education; “‘Tis that saves many a Man’s Life; and the Romans thought it so necessary, that they rank’d it with Letters; and it was the common Phrase to mark one ill educated, and good for nothing, that he had neither learnt to read nor to swim; Nec Literas didicit nec Natare. But besides the gaining a Skill which may serve him at Need, the Advantages to Health by often Bathing in cold Water during the Heat of the Summer, are so many, that I think nothing need be said to encourage it.”

‘Tis some Advantage besides, to be free from the slavish Terrors many of those feel who cannot swim, when they are oblig’d to be on the Water even in crossing a Ferry.

Mr. Hutchinson, in his Dialogues concerning Education, 2 Vols. Octavo, lately publish’d, says, Vol. 2. p. 297. “I would have the Youth accustomed to such Exercises as will harden their Constitution, as Riding, Running, Swimming, Shooting, and the like.”

Charlemagne, Founder of the German Empire, brought up his Sons hardily, and even his Daughters were inur’d to Industry. Henry the Great of France, saith Mons. Rhodez, “was not permitted by his Grand-father to be brought up with Delicacy, who well knew that seldom lodgeth other than a mean and feeble Spirit in an effeminate and tender Body. He commanded that the Boy should be accustomed to run, to leap, to climb the Rocks and Mountains; that by such Means he might be inured to Labour, &c . His ordinary Food also was of coarse Bread, Beef, Cheese and Garlick; his Cloathing plain and coarse, and often he went barefoot and bareheaded.” Walker of Education, p. 17, 18.

9. Drawing is a kind of Universal Language, understood by all Nations. A Man may often express his Ideas, even to his own Countrymen, more clearly with a Lead Pencil, or Bit of Chalk, than with his Tongue. And many can understand a Figure, that do not comprehend a Description in Words, tho’ ever so properly chosen. All Boys have an early Inclination to this Improvement, and begin to make Figures of Animals, Ships, Machines, &c. as soon as they can use a Pen: But for want of a little Instruction at that Time, generally are discouraged, and quit the Pursuit.

Mr. Locke says, p. 234. “When your Son can write well and quick, I think it may be convenient not only to continue the Exercise of his Hand in Writing, but also to improve the Use of it further in Drawing; a Thing very useful to a Gentleman on several Occasions; but especially if he travel; as that which helps a Man often to express in a few Lines well put together, what a whole Sheet of Paper in Writing would not be able to represent and make intelligible. How many Buildings may a Man see, how many Machines and Habits meet with, the Ideas whereof would be easily retain’d, and communicated by a little Skill in Drawing; which being committed to Words, are in Danger to be lost, or at best but ill retained in the most exact Descriptions? I do not mean that I would have him a perfect Painter; to be that to any tolerable Degree, will require more Time than he can spare from his other Improvements of greater Moment. But so much Insight into Perspective and Skill in Drawing, as will enable him to represent tolerably on Paper any Thing he sees, except Faces, may, I think, be got in a little Time.”

Drawing is no less useful to a Mechanic than to a Gentleman. Several Handicrafts seem to require it; as the Carpenter’s, Shipwright’s, Engraver’s, Painter’s, Carver’s, Cabinet-maker’s, Gardiner’s, and other Businesses. By a little Skill of this kind, the Workman may perfect his own Idea of the Thing to be done, before he begins to work; and show a Draft for the Encouragement and Satisfaction of his Employer.

10. Mr. Locke is of Opinion, p. 269. that a Child should be early enter’d in Arithmetick, Geography, Chronology, History and Geometry. “Merchants Accounts, he says, if it is not necessary to help a Gentleman to get an Estate, yet there is nothing of more Use and Efficacy to make him preserve the Estate he has. ‘Tis seldom observ’d that he who keeps an Account of his Income and Expences, and thereby has constantly under View the Course of his Domestic Affairs, lets them run to Ruin: And I doubt not but many a Man gets behind-hand before he is aware, or runs farther on when he is once in, for want of this Care, or the Skill to do it. I would therefore advise all Gentlemen to learn perfectly Merchants Accounts; and not to think ’tis a Skill that belongs not to them, because it has received its Name, and has been chiefly practis’d by Men of Traffick.” p. 316.

Not only the Skill, but the Habit of keeping Accounts, should be acquir’d by all, as being necessary to all.

11. Mr. Locke, speaking of Grammar, p. 252. says, “That to those the greatest Part of whose Business in this World is to be done with their Tongues, and with their Pens, it is convenient, if not necessary, that they should speak properly and correctly, whereby they may let their Thoughts into other Mens Minds the more easily, and with the greater Impression. Upon this Account it is, that any sort of Speaking, so as will make him be understood, is not thought enough for a Gentleman. He ought to study Grammar, among the other Helps of Speaking well, but it must be THE GRAMMAR OF HIS OWN TONGUE, of the Language he uses, that he may understand his own Country Speech nicely, and speak it properly, without shocking the Ears of those it is addressed to with Solecisms and offensive Irregularities. And to this Purpose Grammar is necessary; but it is the Grammar only of their own proper Tongues, and to those who would take Pains in cultivating their Language, and perfecting their Stiles. Whether all Gentlemen should not do this, I leave to be considered, since the Want of Propriety and Grammatical Exactness is thought very misbecoming one of that Rank, and usually draws on one guilty of such Faults, the Imputation of having had a lower Breeding and worse Company than suits with his Quality. If this be so (as I suppose it is) it will be Matter of Wonder, why young Gentlemen are forc’d to learn the Grammars of foreign and dead Languages, and are never once told of the Grammar of their own Tongues. They do not so much as know there is any such Thing, much less is it made their Business to be instructed in it. Nor is their own Language ever propos’d to them as worthy their Care and Cultivating, tho’ they have daily Use of it, and are not seldom, in the future Course of their Lives, judg’d of by their handsome or awkward Way of expressing themselves in it. Whereas the Languages whose Grammars they have been so much employed in, are such as probably they shall scarce ever speak or write; or if upon Occasion this should happen, they should be excused for the Mistakes and Faults they make in it. Would not a Chinese, who took Notice of this Way of Breeding, be apt to imagine, that all our young Gentlemen were designed to be Teachers and Professors of the dead Languages of foreign Countries, and not to be Men of Business in their own.” Page 255. the same Author adds, “That if Grammar ought to be taught at any Time, it must be to one that can speak the Language already; how else can he be taught the Grammar of it? This at least is evident from the Practice of the wise and learned Nations among the Antients. They made it a Part of Education to cultivate their own, not foreign Tongues. The Greeks counted all other Nations barbarous, and had a Contempt for their Languages. And though the Greek Learning grew in Credit amongst the Romans towards the End of their Commonwealth, yet it was the Roman Tongue that was made the Study of their Youth: Their own Language they were to make Use of, and therefore it was their own Language they were instructed and exercised in.” And p. 281. “There can scarce be a greater Defect (says he) in a Gentleman, than not to express himself well either in Writing or Speaking. But yet I think I may ask the Reader, whether he doth not know a great many, who live upon their Estates, and so, with the Name, should have the Qualities of Gentlemen, who cannot so much as tell a Story as they should, much less speak clearly and persuasively in any Business. This I think not to be so much their Fault as the Fault of their Education.” Thus far Locke.

Mons. Rollin, reckons the Neglect of Teaching their own Tongue a great Fault in the French Universities. He spends great Part of his first Vol. of Belles Lettres, on that Subject; and lays down some excellent Rules or Methods of Teaching French to Frenchmen grammatically, and making them Masters therein, which are very applicable to our Language, but too long to be inserted here. He practis’d them on the Youth under his Care with great Success.

Mr. Hutchinson, Dial. p. 297. says, “To perfect them in the Knowledge of their Mother Tongue, they should learn it in the Grammatical Way, that they may not only speak it purely, but be able both to correct their own Idiom, and afterwards enrich the Language on the same Foundation.”

Dr. Turnbull, in his Observations on a liberal Education, says, p. 262. “The Greeks, perhaps, made more early Advances in the most useful Sciences than any Youth have done since, chiefly on this Account, that they studied no other Language but their own. This no Doubt saved them very much Time; but they applied themselves carefully to the Study of their own Language, and were early able to speak and write it in the greatest Perfection. The Roman Youth, though they learned the Greek, did not neglect their own Tongue, but studied it more carefully than we now do Greek and Latin, without giving ourselves any Trouble about our own Tongue.”

Mons. Simon, in an elegant Discourse of his among the Memoirs of the Academy of Belles Lettres at Paris, speaking of the Stress the Romans laid on Purity of Language and graceful Pronunciation, adds, “May I here make a Reflection on the Education we commonly give our Children? It is very remote from the Precepts I have mentioned. Hath the Child arrived to six or seven Years of Age, he mixes with a Herd of ill-bred Boys at School, where under the Pretext of Teaching him Latin, no Regard is had to his Mother Tongue. And what happens? What we see every Day. A young Gentleman of eighteen, who has had this Education, CANNOT READ. For to articulate the Words, and join them together, I do not call Reading, unless one can pronounce well, observe all the proper Stops, vary the Voice, express the Sentiments, and read with a delicate Intelligence. Nor can he speak a Jot better. A Proof of this is, that he cannot write ten Lines without committing gross Faults; and because he did not learn his own Language well in his early Years, he will never know it well. I except a few, who being afterwards engaged by their Profession, or their natural Taste, cultivate their Minds by Study. And yet even they, if they attempt to write, will find by the Labour Composition costs them, what a Loss it is, not to have learned their Language in the proper Season. Education among the Romans was upon a quite different Footing. Masters of Rhetoric taught them early the Principles, the Difficulties, the Beauties, the Subtleties, the Depths, the Riches of their own Language. When they went from these Schools, they were perfect Masters of it, they were never at a Loss for proper Expressions; and I am much deceived if it was not owing to this, that they produced such excellent Works with so marvellous Facility.”

Pliny, in his Letter to a Lady on chusing a Tutor for her Son, speaks of it as the most material Thing in his Education, that he should have a good Latin Master of Rhetoric, and recommends Julius Genitor for his eloquent, open and plain Faculty of Speaking. He does not advise her to a Greek Master of Rhetoric, tho’ the Greeks were famous for that Science; but to a Latin Master, because Latin was the Boy’s Mother Tongue. In the above Quotation from Mons. Simon, we see what was the Office and Duty of the Master of Rhetoric.

12. This Mr. Locke recommends, Educ. p. 284. and says, “The Writing of Letters has so much to do in all the Occurrences of human Life, that no Gentleman can avoid shewing himself in this Kind of Writing. Occasions will daily force him to make this Use of his Pen, which, besides the Consequences that, in his Affairs, the well or ill managing it often draws after it, always lays him open to a severer Examination of his Breeding, Sense and Abilities, than oral Discourses, whose transient Faults dying for the most Part with the Sound that gives them Life, and so not subject to a strict Review, more easily escape Observation and Censure.” He adds,

“Had the Methods of Education been directed to their right End, one would have thought this so necessary a Part could not have been neglected, whilst Themes and Verses in Latin, of no Use at all, were so constantly every where pressed, to the Racking of Childrens Inventions beyond their Strength, and hindring their chearful Progress by unnatural Difficulties. But Custom has so ordained it, and who dares disobey? And would it not be very unreasonable to require of a learned Country Schoolmaster (who has all the Tropes and Figures in Farnaby‘s Rhetorick at his Finger’s Ends) to teach his Scholar to express himself handsomely in English, when it appears to be so little his Business or Thought, that the Boy’s Mother (despised, ’tis like, as illiterate for not having read a System of Logic or Rhetoric) outdoes him in it?

“To speak and write correctly, gives a Grace, and gains a favourable Attention to what one has to say: And since ’tis English that an Englishman will have constant Use of, that is the Language he should chiefly cultivate, and wherein most Care should be taken to polish and perfect his Stile. To speak or write better Latin than English, may make a Man be talk’d of, but he will find it more to his Purpose to express himself well in his own Tongue, that he uses every Moment, than to have the vain Commendation of others for a very insignificant Quality. This I find universally neglected, nor no Care taken any where to improve young Men in their own Language, that they may thoroughly understand and be Masters of it. If any one among us have a Facility or Purity more than ordinary in his Mother Tongue, it is owing to Chance, or his Genius, or any Thing, rather than to his Education, or any Care of his Teacher. To mind what English his Pupil speaks or writes, is below the Dignity of one bred up among Greek and Latin, tho’ he have but little of them himself. These are the Learned Languages, fit only for Learned Men to meddle with and teach: English is the Language of the illiterate Vulgar. Though the Great Men among the Romans were daily exercising themselves in their own Language; and we find yet upon Record the Names of Orators who taught some of their Emperors Latin, tho’ it were their Mother Tongue. ‘Tis plain the Greeks were yet more nice in theirs. All other Speech was barbarous to them but their own, and no foreign Language appears to have been studied or valued amongst that learned and acute People; tho’ it be past Doubt, that they borrowed their Learning and Philosophy from abroad.

“I am not here speaking against Greek and Latin. I think Latin at least ought to be well understood by every Gentleman. But whatever foreign Languages a young Man meddles with, that which he should critically study, and labour to get a Facility, Clearness and Elegancy to express himself in, should be his own; and to this Purpose he should daily be EXERCISED in it.”

To the same Purpose writes a Person of eminent Learning in a Letter to Dr. Turnbull: “Nothing certainly (says he) can be of more Service to Mankind than a right Method of Educating the Youth, and I should be glad to hear —— —— to give an Example of the great Advantage it would be to the rising Age, and to our Nation. When our publick Schools were first establish’d, the Knowledge of Latin was thought Learning; and he that had a tolerable Skill in two or three Languages, tho’ his Mind was not enlightened by any real Knowledge, was a profound Scholar. But it is not so at present; and People confess, that Men may have obtained a Perfection in these, and yet continue deeply ignorant. The Greek Education was of another Kind [which he describes in several Particulars, and adds] They studied to write their own Tongue more accurately than we do Latin and Greek. But where is English taught at present? Who thinks it of Use to study correctly that Language which he is to use every Day in his Life, be his Station ever so high, or ever so insignificant. It is in this the Nobility and Gentry defend their Country, and serve their Prince in Parliament; in this the Lawyers plead, the Divines instruct, and all Ranks of People write their Letters, and transact all their Affairs; and yet who thinks it worth his learning to write this even accurately, not to say politely? Every one is suffer’d to form his Stile by Chance; to imitate the first wretched Model which falls in his Way, before he knows what is faulty, or can relish the Beauties of a just Simplicity. Few think their Children qualified for a Trade till they have been whipt at a Latin School for five or six Years, to learn a little of that which they are oblig’d to forget; when in those Years right Education would have improv’d their Minds, and taught them to acquire Habits of Writing their own Language easily under right Direction; and this would have been useful to them as long as they lived.” Introd. p. 3, 4, 5.

Since Mr. Locke‘s Time, several good Grammars have been wrote and publish’d for the Use of Schools; as Brightland‘s, Greenwood‘s, &c.

13. By Pronunciation is here meant, the proper Modulation of the Voice, to suit the Subject with due Emphasis, Action, &c . In delivering a Discourse in Publick, design’d to persuade, the Manner, perhaps, contributes more to Success, than either the Matter or Method. Yet the two latter seem to engross the Attention of most Preachers and other Publick Speakers, and the former to be almost totally neglected.

14. As nothing teaches (saith Mr. Locke) so nothing delights more than HISTORY. The first of these recommends it to the Study of grown Men, the latter makes me think it the fittest for a young Lad, who as soon as he is instructed in Chronology, and acquainted with the several Epochas in Use in this Part of the World, and can reduce them to the Julian Period, should then have some History put into his Hand. Educ. p. 276.

Mons. Rollin complains, that the College Education in France is defective in Teaching History, which he thinks may be made of great Advantage to Youth. This he demonstrates largely in his Belles Lettres, to the Satisfaction of all that read the Book. He lays down the following Rules for Studying History, viz. 1. To reduce the Study to Order and Method. 2. To observe what relates to Usages and Customs. 3. To enquire particularly, and above all Things, after the Truth. 4. To endeavour to find out the Causes of the Rise and Fall of States, of the Gaining or Losing of Battles, and other Events of Importance. 5. To study the Character of the Nations and great Men mentioned in History. 6. To be attentive to such Instructions as concern MORAL EXCELLENCY and the CONDUCT OF LIFE. 7. Carefully to note every Thing that relates to RELIGION. Vol. 3. p. 146.

15. Plenty of these are to be met with in Montfaucon; and other Books of Antiquities.

16. For the Importance and Necessity of moral Instructions to Youth, see the latter Notes.

17. Dr. Turnbull, Liberal Education, p. 371, says, “That the useful Lessons which ought to be inculcated upon Youth, are much better taught and enforced from Characters, Actions, and Events, developing the inward Springs of human Conduct, and the different Consequences of Actions, whether with Respect to private or publick Good, than by abstract Philosophical Lectures. History points out in Examples, as in a Glass, all the Passions of the human Heart, and all their various Workings in different Circumstances, all the Virtues and all the Vices human Nature is capable of; all the Snares, all the Temptations, all the Vicissitudes and Incidents of human Life; and gives Occasion for Explaining all the Rules of Prudence, Decency, Justice and Integrity, in private Oeconomy, and in short all the Laws of natural Reason.”

18. “Rules are best understood, when Examples that confirm them, and point out their Fitness or Necessity, naturally lead one, as it were by the Hand, to take Notice of them. One who is persuaded and moved by a Speech, and heartily admires its Force and Beauty, will with Pleasure enter into a critical Examination of its Excellencies; and willingly lay up in his Mind the Rules of Rhetoric such an Example of Eloquence plainly suggests. But to teach Rules abstractly, or without Examples, and before the agreeable Effects the Observance of them tends to produce (which are in Reality their Reason or Foundation) have been felt, is exceedingly preposterous.” Turnbull, p. 410.

“I have seldom or never observed any one to get the Skill of Speaking handsomely, by Studying the Rules which pretend to teach Rhetoric.” Locke, p. 279.

19. See Turnbull on this Head, from p. 386 to 390. very much to the Purpose, but too long to be transcribed here.

20. Thus, as Milton says, Educ. p. 381. should they be instructed in the Beginning, End and Reasons of political Societies; that they may not, in a dangerous Fit of the Commonwealth, be such poor, shaken, uncertain Reeds, of such a tottering Conscience, as many of our great Councellors have lately shewn themselves, but stedfast Pillars of the State.

21. After this, they are to dive into the Grounds of Law and legal Justice; deliver’d first and with best Warrant by Moses; and as far as human Prudence can be trusted, in those celebrated Remains of the antient Grecian and Roman Lawgivers, &c . p. 382.

“When he has pretty well digested Tully‘s Offices, says Mr. Locke, p. 277. and added to it Puffendorff de Officio Hominis & Civis, it may be seasonable to set him upon Grotius, de Jure Belli &Pacis, or which perhaps is the better of the two, Puffendorff de Jure naturali & Gentium ; wherein he will be instructed in the natural Rights of Men, and the Original and Foundations of Society, and the Duties resulting from thence. This general Part of Civil Law and History are Studies which a Gentleman should not barely touch at, but constantly dwell upon, and never have done with. A virtuous and well-behaved young Man, that is well versed in the general Part of the Civil Law (which concerns not the Chicane of private Cases, but the Affairs and Intercourse of civilized Nations in general, grounded upon Principles of Reason) understands Latin well, and can write a good Hand, one may turn loose into the World, with great Assurance that he will find Employment and Esteem every where.”

22. Mr. Walker, in his excellent Treatise of the Education of young Gentlemen, speaking of Publick and open Argumentation pro and con, says p. 124, 125. “This is it which brings a Question to a Point, and discovers the very Center and Knot of the Difficulty. This warms and activates the Spirit in the Search of Truth, excites Notions, and by replying and frequent Beating upon it, cleanseth it from the Ashes, and makes it shine and flame out the clearer. Besides, it puts them upon a continual Stretch of their Wits to defend their Cause, it makes them quick in Replies, intentive upon their Subject; where the Opponent useth all Means to drive his Adversary from his Hold; and the Answerer defends himself sometimes with the Force of Truth, sometimes with the Subtilty of his Wit; and sometimes also he escapes in a Mist of Words, and the Doubles of a Distinction, whilst he seeks all Holes and Recesses to shelter his persecuted Opinion and Reputation. This properly belongeth to the Disputations which are Exercises of young Students, who are by these Velitations and in this Palaestra brought up to a more serious Search of Truth. And in them I think it not a Fault to dispute for Victory, and to endeavour to save their Reputation; nor that their Questions and Subjects are concerning Things of small Moment and little Reality; yea, I have known some Governors that have absolutely forbidden such Questions, where the Truth was of Concernment, on purpose that the Youth might have the Liberty of exerting their Parts to the uttermost, and that there might be no Stint to their Emulation.”

23. Rollin, Vol. 4. p. 211. speaking of Natural Philosophy, says, “That much of it falls within the Capacity of all Sorts of Persons, even of Children. It consists in attending to the Objects with which nature presents us, in considering them with Care, and admiring their different Beauties, &c . Searching out their secret Causes indeed more properly belongs to the Learned.

“I say that even Children are capable of Studying Nature, for they have Eyes, and don’t want Curiosity; they ask Questions, and love to be informed; and here we need only awaken and keep up in them the Desire of Learning and Knowing, which is natural to all Mankind. Besides this Study, if it is to be called a Study, instead of being painful and tedious, is pleasant and agreeable; it may be used as a Recreation, and should usually be made a Diversion. It is inconceivable, how many Things Children are capable of, if all the Opportunities of Instructing them were laid hold of, with which they themselves supply us.

“A Garden, a Country, a Plantation, are all so many Books which lie open to them; but they must have been taught and accustomed to read in them. Nothing is more common amongst us than the Use of Bread and Linnen. How seldom do Children know how either of them are prepared, through how many Operations and Hands the Corn and Flax must pass, before they are turned into Bread and Linnen? The same may be said of Cloth, which bears no Resemblance to the Wool whereof it is formed, any more than Paper to the Rags which are picked up in the Streets: And why should not Children be instructed in these wonderful Works of Nature and Art which they every Day make Use of without reflecting upon them?

“He adds, that a careful Master may in this Way enrich the Mind of his Disciple with a great Number of useful and agreeable Ideas, and by a properMixture of short Reflections, will at the same Time take Care to form his Heart, and lead him by Nature to Religion.”

Milton also recommends the Study of Natural Philosophy to Youth, Educ. p. 380. “In this, says he, they may proceed leisurely from the History of Meteors, Minerals, Plants and living Creatures, as far as Anatomy; Then also in Course might be read to them out of some not tedious Writer, the Institution of Physick; that they may know the Tempers, the Humours, the Seasons, and how to manage a Crudity; which he who can wisely and timely do, is not only a great Physician to himself, and to his Friends, but also may at some Time or other save an Army by this frugal and expenseless Means only; and not let the healthy and stout Bodies of young Men rot away under him for want of this Discipline, which is a great Pity, and no less a Shame to the Commander.”

Proper Books may be, Ray’s Wisdom of God in the Creation, Derham’s Physico-Theology, Spectacle de la Nature, &c.

24. Milton would have the Latin Authors on Agriculture taught at School, as Cato, Varro and Columella; “for the Matter, says he, is most easy, and if the Language be difficult, yet it may be master’d. And here will be an Occasion of inciting and enabling them hereafter to improve the Tillage of their Country, to recover the bad Soil, and to remedy the Waste that is made of Good; for this was one of Hercules‘ raises.” Educ. p. 379.

Hutcheson (Dialogues on Educ. 303, 2d Vol.) says, “Nor should I think it below the Dignity or Regard of an University, to descend even to the general Precepts of Agriculture and Gardening. Virgil, Varro, and others eminent in Learning, tho’t it not below their Pen—– and why should we think meanly of that Art, which was the Mother of Heroes, and of the Masters of the World.”

Locke also recommends the Study of Husbandry and Gardening, as well as gaining an Insight in several of the manual Arts; Educ. p. 309, 314, 315. It would be a Pleasure and Diversion to Boys to be led now and then to the Shops of Artificers, and suffer’d to spend some Time there in observing their Manner of Working. For the Usefulness of Mechanic Skill, even to Gentlemen, see the Pages above cited, to which much might be added.

25. How many Mills are built and Machines constructed, at great and fruitless Expence, which a little Knowledge in the Principles of Mechanics would have prevented?

26. We are often told in the Journals of Travellers, that such and such Things are done in foreign Countries, by which Labour is sav’d, and Manufactures expedited, &c . but their Description of the Machines or Instruments used, are quite unintelligible for want of good Drafts. Copying Prints of Machines is of Use to fix the Attention on the several Parts, their Proportions, Reasons, Effects, &c . A Man that has been us’d to this Practice, is not only better able to make a Draft when the Machine is before him, but takes so much better Notice of its Appearance, that he can carry it off by Memory when he has not the opportunity of Drawing it on the Spot. Thus may a Traveller bring home Things of great Use to his Country.

27. “Upon this excellent Disposition (says Turnbull, p. 326.) it will be easy to build that amiable Quality commonly called GOOD BREEDING, and upon no other Foundation can it be raised. For whence else can it spring, but from a general Good-will and Regard for all People, deeply rooted in the Heart, which makes any one that has it, careful not to shew in his Carriage, any Contempt, Disrespect, or Neglect of them, but to express a Value and Respect for them according to their Rank and Condition, suitable to the Fashion and Way of their Country? ‘Tis a Disposition to make all we converse with easy and well pleased.”

28. It is this lovely Quality which gives true Beauty to all other Accomplishments, or renders them useful to their Possessor, in procuring him the Esteem and Good-will of all that he comes near. Without it, his other Qualities, however good in themselves, make him but pass for proud, conceited, vain or foolish. Courage, says an excellent Writer, in an ill-bred Man has the Air, and escapes not the Opinion of Brutality; Learning becomes Pedantry; Wit, Buffoonery; Plainness, Rusticity; and there cannot be a good Quality in him which Ill-breeding will not warp and disfigure to his Disadvantage.” Turnbull, p. 327.

29. To have in View the Glory and Service of God, as some express themselves, is only the same Thing in other Words. For Doing Good to Men is the only Service of God in our Power; and to imitate his Beneficence is to glorify him. Hence Milton says, “The End of Learning is to repair the Ruins of our first Parents, by regaining to know God aright, and out of that Knowledge to love him, to imitate him, to be like him, as we may the nearest by possessing our Souls of true Virtue.” Educ. p. 373. Mr. Hutcheson says, Dial. v. 2. p. 97. “The principal End of Education is, to form us wise and good Creatures, useful to others, and happy ourselves. The whole Art of Education lies within a narrow Compass, and is reducible to a very simple Practice; namely, To assist in unfolding those Natural and Moral Powers with which Man is endowed, by presenting proper Objects and Occasions; to watch their Growth that they be not diverted from their End, or disturbed in their Operation by any foreign Violence; and gently to conduct and apply them to all the Purposes of private and of public Life.” And Mr. Locke (p. 84. Educ.) says, “‘Tis VIRTUE, then, direct VIRTUE, which is to be aim’d at in Education. All other Considerations and Accomplishments are nothing in Comparison to this. This is the solid and substantial Good, which Tutors should not only read Lectures and talk of, but the Labour and Art of Education should furnish the Mind with, and fasten there, and never cease till the young Man had a true Relish of it, and plac’d his Strength, his Glory, and his Pleasure, in it.” And Mons. Rollin, Belles Lettres, Vol. 4. p. 249. to the same Purpose, “If we consult our Reason ever so little, it is easy to discern that the END which Masters should have in View, is not barely to teach their Scholars Greek and Latin, to learn them to make Exercises and Verses, to charge their Memory with Facts and historical Dates, to draw up Syllogisms in Form, or to trace Lines and Figures upon Paper. These Branches of Learning I own are useful and valuable, but as Means, and not as the End; when they conduct us to other Things, and not when we stop at them; when they serve us as Preparatives and Instruments for better Knowledge, without which the rest would be useless. Youth would have Cause to complain, if they were condemned to spend eight or ten of the best Years of their Life in learning, at a great Expence, and with incredible Pains, one or two Languages, and some other Matters of a like Nature, which perhaps they would seldom have Occasion to use. The End of Masters, in the long Course of their Studies, is to habituate their Scholars to serious Application of Mind, to make them love and value the Sciences, and to cultivate in them such a Taste, as shall make them thirst after them when they are gone from School; to point out the Method of attaining them; and make them thoroughly sensible of their Use and Value; and by that Means dispose them for the different Employments to which it shall please God to call them. Besides this, the End of Masters should be, to improve their Hearts and Understandings, to protect their Innocence, to inspire them with Principles of Honour and Probity, to train them up to good Habits; to correct and subdue in them by gentle Means, the ill Inclinations they shall be observed to have, such as Pride, Insolence, an high Opinion of themselves, and a saucy Vanity continually employed in lessening others; a blind Self-love solely attentive to its own Advantage; a Spirit of Raillery which is pleased with offending and insulting others; an Indolence and Sloth, which renders all the good Qualities of the Mind useless.”

Dr. Turnbull has the same Sentiments, with which we shall conclude this Note. If, says he, there be any such Thing as DUTY, or any such Thing as HAPPINESS; if there be any Difference between right and wrong Conduct; any Distinction between Virtue and Vice, or Wisdom and Folly; in fine, if there be any such Thing as Perfection or Imperfection belonging to the rational Powers which constitute moral Agents; or if Enjoyments and Pursuits admit of Comparison; Good Education must of Necessity be acknowledged to mean, proper Care to instruct early in the Science of Happiness and Duty, or in the Art of Judging and Acting aright in Life. Whatever else one may have learned, if he comes into the World from his Schooling and Masters, quite unacquainted with the Nature, Rank and Condition, of Mankind, and the Duties of human Life (in its more ordinary Circumstances at least) he hath lost his Time; he is not educated; he is not prepared for the World; he is not qualified for Society; he is not fitted for discharging the proper Business of Man. The Way therefore to judge whether Education be on a right Footing or not, is to compare it with the END; or to consider what it does in order to accomplish Youth for choosing and behaving well in the various Conditions, Relations and Incidents, of Life. If Education be calculated and adapted to furnish young Minds betimes with proper Knowledge for their Guidance and Direction in the chief Affairs of the World, and in the principal Vicissitudes to which human Concerns are subject, then is it indeed proper or right Education. But if such Instruction be not the principal Scope to which all other Lessons are rendered subservient in what is called the Institution of Youth, either the Art of Living and Acting well is not Man’s most important Business, or what ought to be the CHIEF END of Education is neglected, and sacrificed to something of far inferior Moment. Observations on Liberal Education, p. 175, 176.