Over the years the Undergraduate Council and the WSGA began to lose their importance to the student body. During the 1960-1961 academic year, the Undergraduate Council abolished itself in favor of a new government which was to take office in the Spring of 1962; at the same time, the Women’s Student Government Association realigned itself in a fashion similar to that of the new student government for male students. In the meantime, a transitional government was put in place. The new government was designed to be more representational of the independent voice on campus and included nine standing committees with a broad range of powers and duties. The new government called the Men’s Student Government (MSG) was accompanied by the realigned Women’s Student Government Association.

The MSG consisted of three main branches: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial. The legislative branch made regulations for student clubs and student life. The executive branch acted on financial matters and distributed money to student clubs and for campus events. The judicial branch decided disciplinary matters, but, like the Undergraduate Council before it, the Provost only permitted the judicial branch to hear the cases he assigned it. The MSG was led by a president elected by its assembly (the officers of the legislative branch), not by a directly elected president.

The realigned WSGA featured a Judicial Board that had the power to hear all violations of the University’s social regulations by female students, even without having the case referred to it by the administration. The Judicial Board, however, did not have the power to hear any violations of the academic regulations by female students. The new Judicial Board was advised by the Advisor of Women (who did not have a vote of the Board) and was composed of nine female student justices, two from each undergraduate class and one Chief Justice elected by all of Penn’s female undergraduates. The new WSGA also included a Fraternity Parliament and a Dormitory Parliament established as forums for the voices of female students living in fraternities and dormitories.

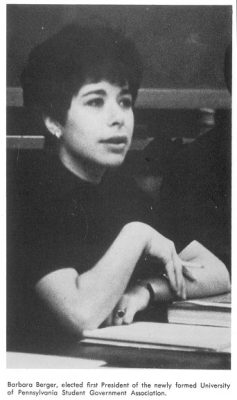

Although they were created as entirely separate organizations, the MSG and the new WSGA did not remain independent for long. The 1966 Record shows the beginning of the combination of the MSG and the WSGA. The Record of the following year shows that in the winter of 1967 the Men’s and Women’s student government organizations at Penn formally merged creating the University of Pennsylvania Student Government (UPSG), the first student government organization at Penn that truly included all Penn students. Seventy years after the creation of the Houston Club, all Penn students were finally fully represented by a student government organization. For the 1966-1967 academic year, the UPSG’s first president was Barbara Berger, the former WSGA president. With the creation of the UPSG, the men’s and women’s judicial boards worked together, co-ed committees on finance, external affairs, internal affairs, housing and development, elections and activities were also established.Penn students’ role in the governance of the University continued to grow following the creation of the UPSG. In September of 1969 thirty students (fourteen of whom were undergraduates) were added to the University Council, an organization composed of faculty and administrators with wide-ranging powers and influence across the entire University.

Penn’s student government changed again in the spring of 1969 when a group of students who called themselves the University of Pennsylvania Community of Students convinced the UPSG to vote on the creation of a new student government organization. The University of Pennsylvania Community of Students wanted a student government which allowed for more direct participation of all students in governmental affairs. In the years following of the installation of the new Penn student government, most students stopped showing up for student government meetings, thereby rendering the community participation part of the government effectively useless. The Administrative Committee of this new student government was intended to be a vehicle for student concerns. The committee was supposed to wait until students (the community) raised an issue for them to pursue. Once an issue was raised, the committee was supposed to resolve it. As interest in student government waned, this committee had less and less to do and students became increasingly apathetic to its existence. An essay in the 1971 Record openly questioned the motives of the students who chose to serve in the student government. In the years to come, old forms of student government lost their importance to students. The focus instead shifted to student representation on the University Council, the more powerful governance organization at Penn that represented other constituencies at the University, not just students, but also the faculty and the administration.

The shift away from traditional student government at Penn is little more than a representation of the times. College and University students across the nation were voicing their opinions in new ways in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At Penn this trend was manifested as a rejection of student government and the embracing of student representation on the overarching University Council. Reflecting this shift in governmental structure, the Community of Students came to be in charge of setting up the elections for University Council representatives, not student government representatives. Students’ belief that they were integral parts of the University and therefore should be a part of the decision making process never waned. During the late 1960s and early 1970s students simply believed the best way to assume this role was not through governance organizations of their own but through the University’s own governance system.