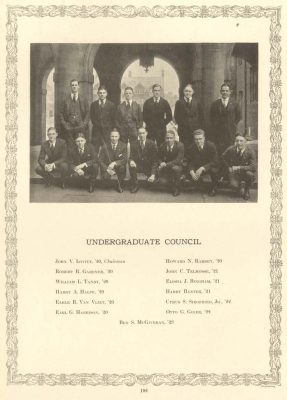

According to the Undergraduate Council’s by-laws from its 1938 constitution, “the purpose of the Council shall be to represent the interest of the male students of the University of Pennsylvania to promote the communal life of the institution and to aid the President and other officers in preserving the morale of the students, in keeping proper order and in maintaining the good name and dignity of the University of Pennsylvania.” The female students on Penn’s campus were clearly not represented by the Undergraduate Council, but instead could be a part of an organization known as the Women’s Undergraduate Assembly. The Women’s Undergraduate Assembly became the Women’s Student Government Association in the fall of 1928 and continued to function for the duration of the existence of the Undergraduate Council.

The composition of the Undergraduate Council changed greatly over the course of its existence. When Penniman empowered the Council to act in University disciplinary measures the Council was composed entirely of seniors. Later it would include members from the sophomore and junior classes as well. For a number of years, the Council included the presidents of the senior societies and the Editor-in-Chief of the Pennsylvanian. Eventually, the Council became representative of a still larger swath of the University as athletic teams, each undergraduate school, and each undergraduate class were represented in due course. The number of students eligible to serve on Council also increased thanks to the elimination of clauses, such as the one which had limited representation to seniors who had matriculated at least two and one half years before the beginning of their senior year were eliminated.

The constitution and by-laws, as presented in a pamphlet put out by the Undergraduate Council of 1926-1927, provides details of the scope of this organization’s activities during the 1920s. Even though Josiah Penniman granted the Council significant powers, he ensured that the Undergraduate Council would never gain enough power to challenge the administration. When Penniman granted the Undergraduate Council the power to discipline students, he mandated that the Council only hear the cases referred by him to it. Penniman’s attempts to keep the Council in its place succeeded; throughout its existence, Provosts retained the ability to overrule any Undergraduate Council decision they deemed not in the best interests of the University.

Over the years, as the transparency of the Council’s proceedings came into question, the Council decided that anyone on campus could inspect the minutes from the council meetings whenever they chose to. The Council thus mandated that the minutes from each meeting be published in the Pennsylvanian. The Council’s democratic nature increased as the constitution was changed to allow meetings to be called anytime so long as four members of the Council agreed that a meeting should occur; previously, members had to wait until the chairman of the Council (for a number of years the senior class president) called a meeting. In order to amend the constitution of the Council to allow for changes such as these, approval was required by a two-thirds majority of the council, by all class presidents, as well as by the Provost of the University.

To be elected to a position on the Undergraduate Council, a student had to first be nominated by handing in at least ten signatures from students who would be eligible to vote for that candidate. Candidates for council positions had to also be deemed academically eligible for office. In order to win an election, a candidate needed to receive more than fifty percent of the vote, guaranteeing that the candidate had the support of a majority of the voters. To ensure that one candidate always received at least fifty percent of the vote, if more than two candidates for one office received the requisite signatures and were deemed academically eligible, a primary election was held one day before the regular election day. The top two finishers from the primary election would advance to the regular election unless the top finisher received more than fifty percent of the vote: in that case there would be no regular election for that position and the top finisher from the primary would be named to the Undergraduate Council.

Disciplinary power was not the only difference between the Undergraduate Council and the Houston Club. The minutes of the Undergraduate Council reveal the number of instances the Council discussed school spirit and the seating and behavior of students at Penn’s football games. It seems as though the Council, when not disciplining students or distributing student activities funds, focused on the ways in which students celebrated their involvement in Penn’s sporting events. The Council’s focus on school spirit included paying for damage caused by large groups of students in riots following Penn football games. The Council, however, refused to pay for damages caused by small groups or individual students during riots following Penn football games, but never explicitly stated what the distinction between large and small groups of students was. It seems likely that the Council would not pay for damage when they could pin-point one or several students who were directly responsible for the damage. The Council’s minutes also show that it had the final say on which outside political organizations could be brought onto campus for events run by student organizations.

For forty years, the Undergraduate Council served Penn’s male students as their governmental voice, dispensing discipline, distributing student activities funds and representing the will of the male students. Penn and its students, however, changed significantly over the years of the Council’s existence. As American society changed following the Great Depression, World War II, and the beginning of the 1960s, Penn’s students became less willing to be governed without their full participation in the government and with an overseer, such as the Provost, able to overrule their decisions at his whim. In other words, Penn students wanted to be more able to participate in government and more able to have their voices heard. These changes in society and in Penn’s students brought about the beginning of the end for the Undergraduate Council and the reorganization of its counterpart, the Women’s Student Government Association.