Ruth Branning Molloy, a poet, writer, photographer, and Philadelphia historian, was born on July 24, 1910, in the Bronx, New York. At the age of fourteen, she graduated from West Philadelphia High School for Girls.

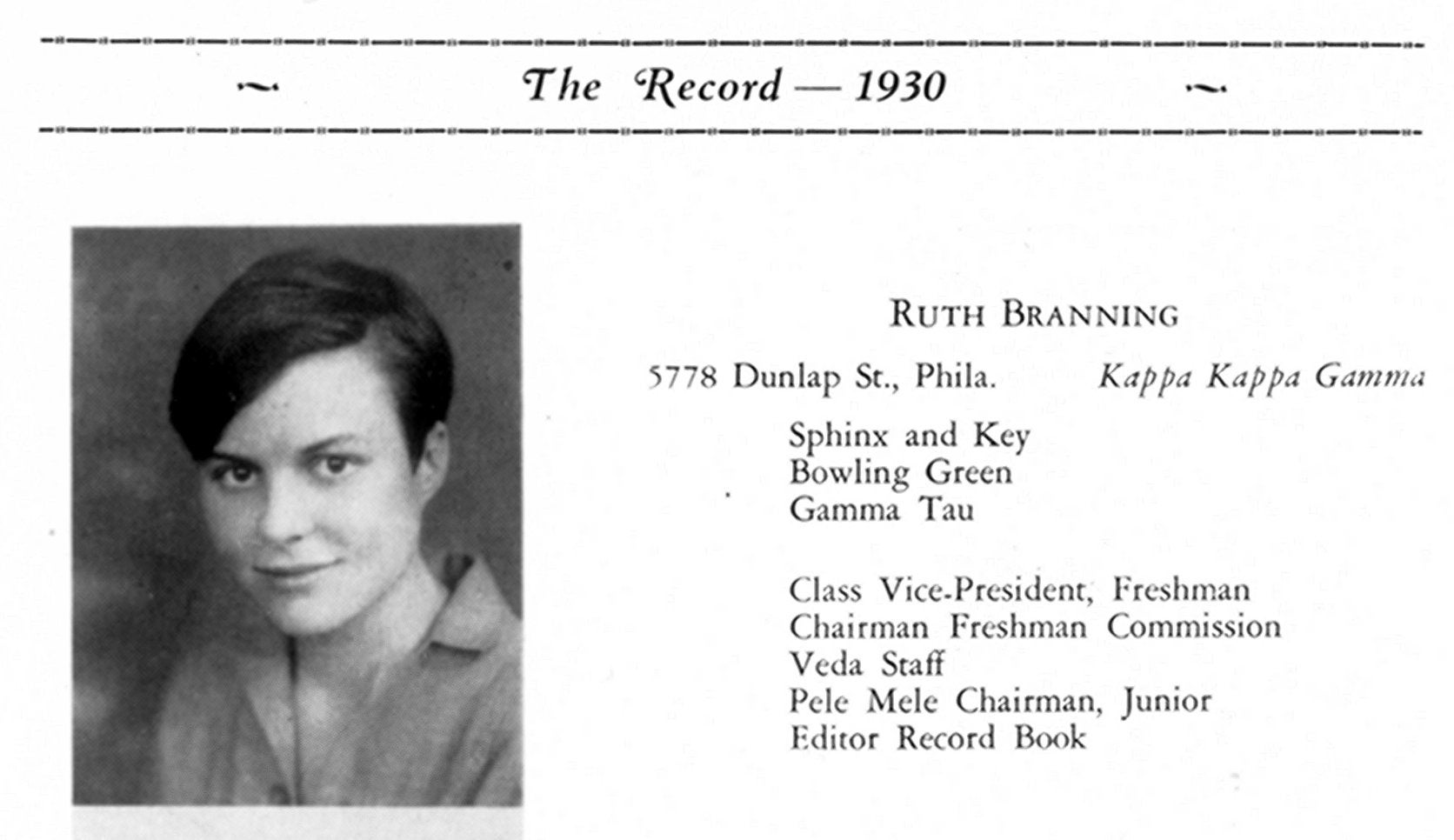

In 1926, Ruth Branning enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, where she participated in many clubs and activities, including Sphinx and Key, Bowling Green, and the Freshman Commission. She was also the editor of the 1930 Record Book, and a member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority.

After earning a B.S. in education from Penn, Ruth Branning went to work for The Philadelphia Inquirer. As an editorial assistant in the library, she researched material for “Everybody’s Column” and “100 Years Ago,” and helped build the department’s reference file. In 1932, she married Joseph E. Molloy, head librarian at The Philadelphia Inquirer. Most of their married life was spent in West Philadelphia, where they raised their three daughters.

Ruth Molloy was a prolific writer of essays, poems and other articles for publications such as the Saturday Evening Post, The Inquirer, The Evening Bulletin, and Mademoiselle and Good Housekeeping magazines. She also took photographs, which were published as photo essays. Her story “Twenty Below, at the End of a Lane,” a fictionalized account of her childhood, originally printed in Mademoiselle magazine, was included in the Best American Short Stories of 1956. She was a regular contributor to The Pennsylvania Gazette.

Molloy was a resident of St. Mark’s Square in University City for 34 years and one of the founders of the University City Historical Society. She often gave tours of the area and spoke about its history to school groups and organizations. In 1983, she initiated the “Adopt-a-Grave” program, designed to preserve the history of graves at Woodland Cemetery in West Philadelphia.

In 2000, Molloy’s book of poems, Finally, illustrated with her photographs, was published by Sutter House. Despite her failing health, she continued to work on her multi-volume history of West Philadelphia until her death, on November 8, 2002.

Ruth Branning Molloy on her years at Penn:

On that first day I sat in a long row of freshmen waiting for an interview with Dean Minnick. To while away the time, I rolled up a small piece of white paper and pretended to be smoking a cigarette. Then my name was called. The dean stood at his door, ready to shake my hand; I was frightened: “I wasn’t really smoking.” “I know that,” said the kindly dean in a forgiving voice. Smoking was forbidden for coeds, although some sneaks puffed away in the rest rooms.

Suddenly I was aware that I was a member of the Class of 1930. The possibilities were enormous: I might go to a dance or see a football game. Season tickets were $10, and we, the women of the hand-picked class, were made aware of a special privilege: we would be the first coeds allowed to buy a season ticket, just the way the men students did. We could even cheer and sing Pennsylvania songs-unlike, I later learned, another institution at which coeds were not allowed to cheer or sing at games, as their high-pitched voices might bother the team.

We have got to remember that women labored and were delighted over each achievement. They learned to mention eventualities as if they were events, to state dreams as future facts, to talk matter-of-factly of dreams: the Valley Forge Campus, a women’s clubhouse, admission to the Wharton School, a College for Women, a Dean of Women, a woman trustee, the privilege of buying a season football ticket, new wallpaper in the girls’ retiring room, bubbling fountains for Bennett Hall!