Nathan Francis Mossell, the son of Aaron and Eliza Bowers Mossell, was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada on July 27, 1856. Nathan’s father, Aaron Mossell, was a grandson of enslaved people, with a great-grandfather known to have been brought from West Africa. His wife Eliza came from a free Black family that had been deported to Trinidad with other such families when she was a child; she and Aaron met after she returned to Baltimore. Aaron’s skill as a brickmaker enabled him to purchase a home for his wife, but as racial discrimination increased and the lack of educational opportunities became a roadblock for the aspirations Aaron and Eliza had for themselves and their children, Aaron quit his job and moved to Canada with his wife, two young sons and a daughter. Settling in Hamilton, Ontario in 1853, Aaron attended night school to become literate and used his savings to establish his own brick-making business.

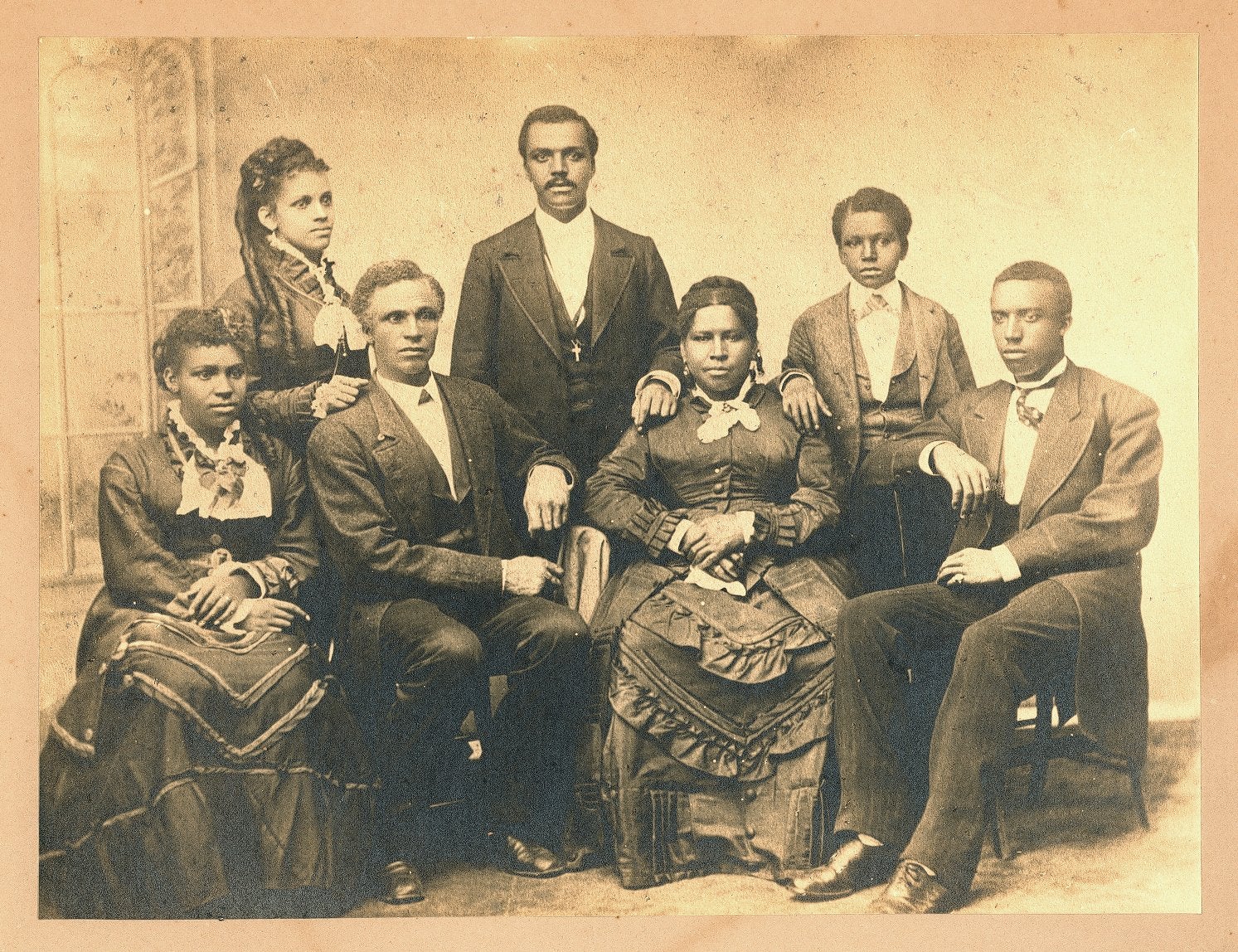

During the Civil War, Aaron Mossell resettled his family, now including six children, in upstate New York. Here he established a successful brick manufacture business, employing laborers of all races and providing bricks for local schools and homes, his African Methodist Episcopal church, and eventually a hotel which he himself owned. Thus it was that Nathan Francis Mossell was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada on July 27, 1856. The 1870 census shows Aaron, sr., as a brick layer with of $2000 of real estate and of $300 of personal estate, living in Lockport, near Niagara, New York. Aaron’s wife Eliza is listed as keeping house. Both Aaron and Eliza are described by the census as having been born in Maryland 46 years earlier. The two eldest children in their household had also been born in Maryland: May, a twenty-two year old fancy needleworker, and Charles, a twenty-year old student at Lincoln University. The younger children (fourteen year old Nathan, twelve year old Alvarilla and six year old Aaron, jr.) had all been born in Canada and were in 1870 attending school in Lockportt; in fact they integrated the Lockport public schools and were responsible for the closing of a one room school house for “colored” children. Another son, falling between Charles and Nathan in age, had recently died and is not listed in the census.

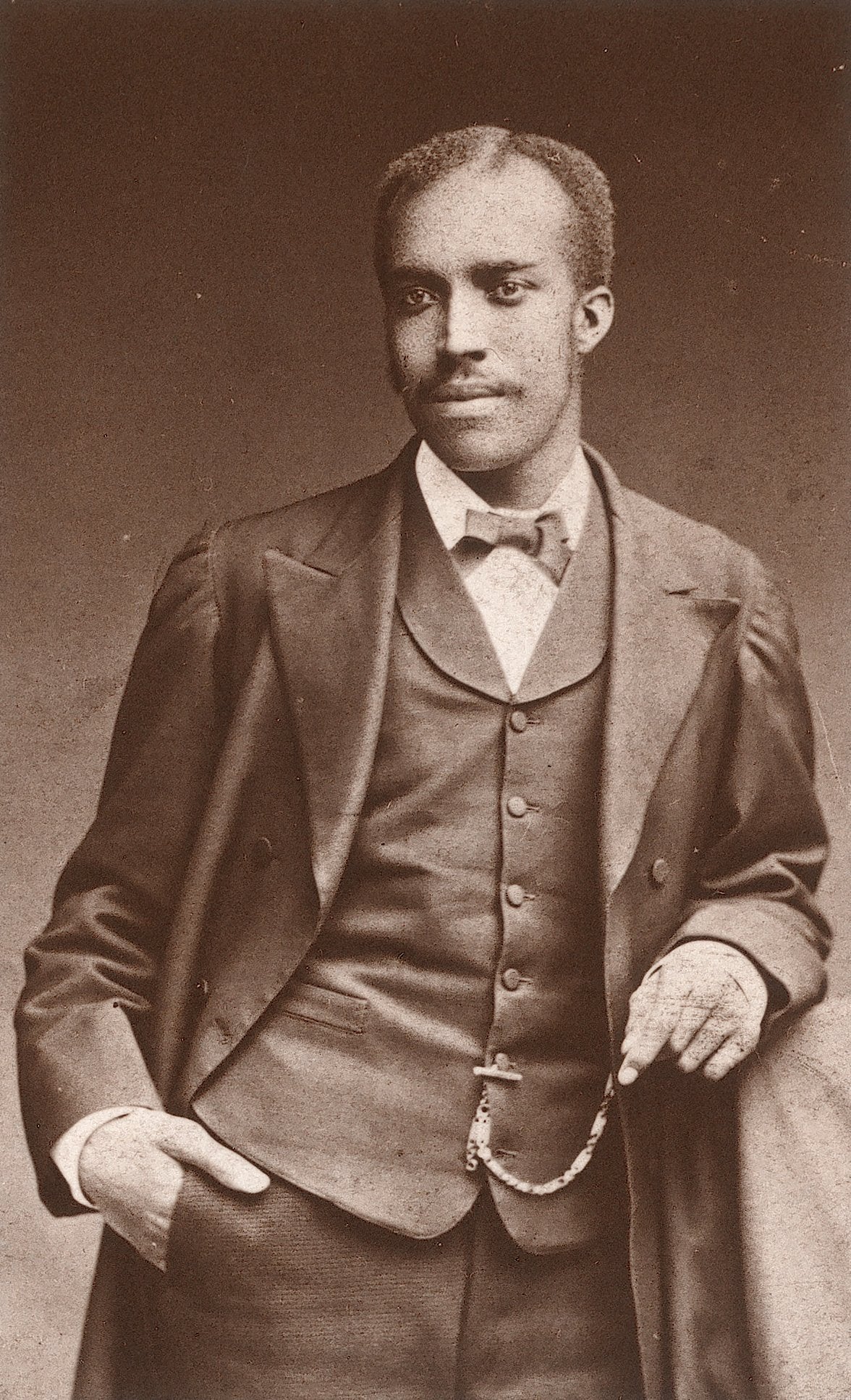

Since Aaron Mossell, sr., at first had only enough resources to send his eldest son to college, Nathan’s schooling became irregular when he began working in his father’s brick yard at age nine. Nathan soon grew to be as strong and tall as most full-grown men; thus it was that, following the death of of his second-oldest brother, Nathan stopped going to school altogether to work full time for his father. In 1871, however, Nathan followed his brother Charles to Lincoln University where he finally had the chance to demonstrate his academic potential. After completing four years of preparatory school in three years, he went on to the complete four years in the college. At the time of his 1879 graduation from Lincoln with a Bachelor of Arts degree, Nathan Francis Mossell took second honors in his class and was awarded the Bradley Medal in Natural Science.

After graduating from Lincoln University, Nathan Mossell entered the Medical School of the University of Pennsylvania. At Penn he took second honors in his medical school class. After graduating in 1882, he became the most prominent of Penn’s first African American students. Upon graduating, Mossell was trained first by Dr. D. Hayes Agnew in the Out-Patient Surgical Clinic of the University Hospital. Because of the difficulties Blacks then encountered in securing internships in this country, Mossell then travelled to England to complete an internship at the Guy’s, Queens College and St. Thomas hospitals in London. In 1888, after his return to Philadelphia, Mossell was elected (after overcoming significant opposition on the basis of his race) to membership in the Philadelphia County Medical Society, making him the first African American physician to achieve this honor.

After opening his office at 924 Lombard Street, young Dr. Mossell quickly began to have an impact on Philadelphia medical practice and on the position of African Americans in the city and beyond. In August of 1895 he became the leading figure in the founding of the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School – the second Black hospital in the United States, and one that would not only treat African American patients, but also offer interships to Black doctors and nursing training to Black women. Dr. Mossell’s former Penn professors (including Agnew, Tyson, Pepper, and Leidy) were among the initial contributors, and Eugene T. Hinson, M. D. 1898, was one of the hospital’s African American physicians. Since its establishment of a 15-bed facility in a house at 1512 Lombard Street, Douglass Hospital has had a history of supporting the African American community in Philadelphia. In 1909, a new building with 75 beds opened at 1534 Lombard Street. In 1948, two years after Mossell’s death, Douglass Hospital merged with another predominantly black hospital, Mercy, to create Mercy Douglass Hospital on Woodland Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets in West Philadelphia. This hospital continued its care of African American Philadelphians until its closing in 1973. Mossell worked for over thirty-five years as the hospital’s chief-of-staff and medical director, retiring in 1933. He continued his private medical practice, however, until shortly before his death in October of 1946, at the age of ninety.

Mossell’s influence was felt in other ways as well. He was a co-founder of the Philadelphia Academy of Medicine and Allied Sciences (an association for African Americans in medicine) in 1900, a founder and director of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1910, and a member of the Niagara Movement organized by W.E.B. DuBois in 1905. During the 1880s and 1890s Mossell was one of the first to pressure for the hiring of Black professors at his alma mater Lincoln University; from 1891 into the 1940s, he pushed for the integration of Girard College. He also worked with state representative Arthur Faucett to pass a bill banning exclusion of Blacks from university housing at Penn.

Nathan Mossell, his wife Gertrude and their two daughters, Mary C. and Florence Alma, lived at 1432 Lombard Street in Philadelphia. He had met Philadelphian Gertrude Bustill (1855-1948) while both were students at Lincoln University; her return to Philadelphia to teach school there and in Camden was a significant motivation in his decision to attend medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. They were married while he was still a medical student. After her marriage Gertrude Bustill Mossell worked as a professional writer and editor, publishing several books and working for such Philadelphia papers as the Press, Times, and Inquirer. After their children were born, she became active in civic causes, especially fund raising for Douglas Hospital and the establishment of the Southwest branch of the YWCA.

Nathan and Gertrude Mossell were part of remarkable extended families. Her great-grandfather had been a baker for George Washington’s army, her grandfather a Hicksite Quaker, and her sister became the mother of singer and actor Paul Robeson. Nathan’s older brother Charles studied theology in Boston after leaving Lincoln University, and later became a missionary in Haiti, where he was joined by Alvarilla Mossell, sister of Nathan and Charles. The older sister, Mary, married a teacher in Princeton, New Jersey. Nathan’s younger brother Aaron Albert Mossell would be the first African American to graduate from Penn’s Law School; although he served for a time as secretary and solicitor of Douglass Hospital and represented Philadelphia Blacks arrested in civil unrest, Aaron left Philadelphia and his family to eventually settle abroad in Wales. Aaron’s daughter (and Nathan’s niece) would be Sadie Tanner Mossell, later married to Raymond Alexander. When Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander earned her Ph.D. from Penn in 1921, she become the first Black person to obtain a Ph.D. in Economics in the United States. She was also the first African American woman to graduate from Penn’s Law School and the first to be admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar.