Francis Johnson was born on June 16, 1792. There is some debate as to whether Johnson was born in Philadelphia or Martinique. The most recent scholarship, however, suggests that Johnson was born in Philadelphia. Johnson became the first African American to publish sheet music (well over two hundred published pieces), the first black musician and perhaps the first American musician to tour Europe with a band, and one of the first musicians to participate in integrated public concerts. He mentored a number of successful black musicians, and scholars credit him as the leader the Philadelphia School of composers — arguably the first such group in the United States. His compositions remained in print until late in the nineteenth century and enjoyed some reemergence in the late twentieth century.

Little is known about Johnson’s childhood and his early musical training and experiences. He was known as a professional musician in Philadelphia in 1812, most likely as a violinist. He may have learned how to play the keyed bugle, an instrument on which Johnson became known as a virtuoso, from an Irish immigrant named Richard Willis who went on to become the leader of the band at the West Point Military Academy. Johnson’s musical talent was recognized when, in 1818, he became the first African American to have a composition published as sheet music. Johnson played a number of different instruments, often changing based on the circumstances of the concerts he played.

Johnson also led a well-known band in the Philadelphia area at a time when very few people could sustain themselves as professional musicians. Johnson’s band, for a number of years composed entirely of African Americans, played solely for the black community when it began. After a few years, however, the band received gigs from prominent white socialites to perform at some of the fanciest and most impressive Philadelphia-area social gatherings. Johnson’s band gained some national recognition when it became associated with all white militia units and began to play concerts at the Summer Resort at Saratoga Springs, the same resort the Philadelphia Orchestra has spent its summers for many years. The band was composed of musicians who were well-known in their own right.

Johnson’s personal fame grew as his band became more and more famous, but also when, in 1824, he composed much of the music to be played at ceremonies honoring Revolutionary War hero General Lafayette upon his return to the United States.

Even while his fame spread, Johnson continued to teach music to white and black people in his three-story Philadelphia studio near 11th and Lombard Streets. From a description of Johnson’s studio by one of his students, Isaac Mickle, it is clear that Johnson’s economic status at least was on a par with that of Philadelphia’s upper-middle class.

In 1837, Johnson became the first African American band leader to take a band to Europe. Johnson’s band played for Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. The young monarch was so taken with Johnson’s musical talent that she gave him a silver bugle as a present. In Europe, Johnson and his band picked up the latest musical trends and brought them back to the United States. When Johnson again began playing concerts in America in the winter of 1838-1839, he introduced waltzes by Johann Strauss and a style of music which developed into what is now known as the very popular classical “pops” style. Johnson also incorporated white musicians into his band, leading to some of the first interracial musical performances in the United States.

Johnson’s fame increased with his American tours that took him as far north as Toronto, west to St. Louis and south to Louisville. Johnson also composed much of the music for an event in honor of the visiting Charles Dickens as well as for celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Washington.

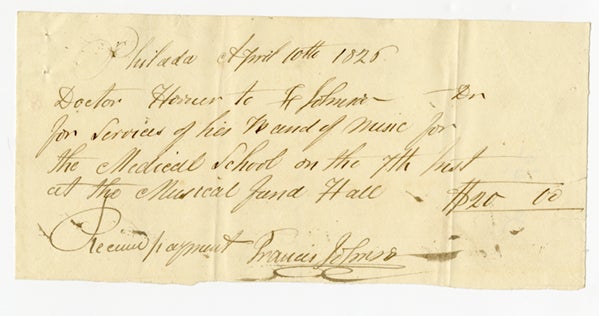

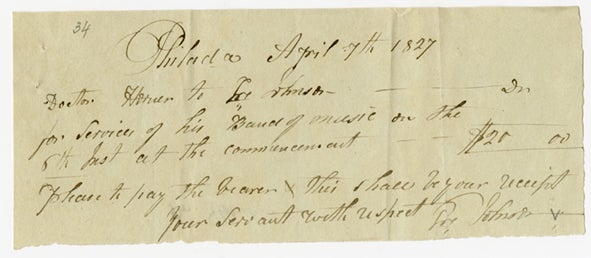

Johnson was paid for leading his band at events at the University of Pennsylvania on several occasions. He appears to have provided the music for the School of Medicine commencement from 1826 to 1841 and another occasion in April of 1842. Records of these payments can be found in the trustee’s minutes of the University as well as the receipts for bills of the School of Medicine. While most bills state they were for playing at the School of Medicine commencement other payments do not specify and were after exhibitions of student declamations held in the winter or spring months.

Obviously, life as an African American in America was not easy in the first half of the 1800s and Johnson and his band often faced racism at their performances. Some all-white bands refused to play at events where Johnson’s band was also booked to play. On several occasions, the crowds at these events did not believe that Johnson and his fellow African American musicians could read the sheet music in front of them, insisting that they were playing the music “by ear.” When Johnson played in St. Louis, Missouri, the city government put out an affidavit for his arrest and eventually kicked him out of town. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he was chased by an angry, violent crowd, and was lucky to escape with only minor injuries.

There are no direct accounts of how Johnson reacted to the virulent racism he faced during his lifetime. What remains as evidence of Johnson’s commitment to equality are his compositions like “The Grave of the Slave” and the “Recognition March on the Independence of Haiti” as well as his continued commitment to play for the black community even after he became hugely popular in the more lucrative white community.

Many aspects of Johnson’s life remain unclear, especially his personal life. He married Helen Appo (sister of his band mate William Appo), but it is not clear when they married and whether or not this was Johnson’s only marriage. He lived at 65 South 4th Street in Philadelphia for much of his life.

Johnson died on April 6, 1844, shortly after passing off his position as the leader of the Francis Johnson Band. His band, however, continued playing for about 20 years after his death and some of his music was rerecorded near the end of the 20th century and released on compact disc. Johnson is sometimes given credit as a forefather of both jazz and ragtime.