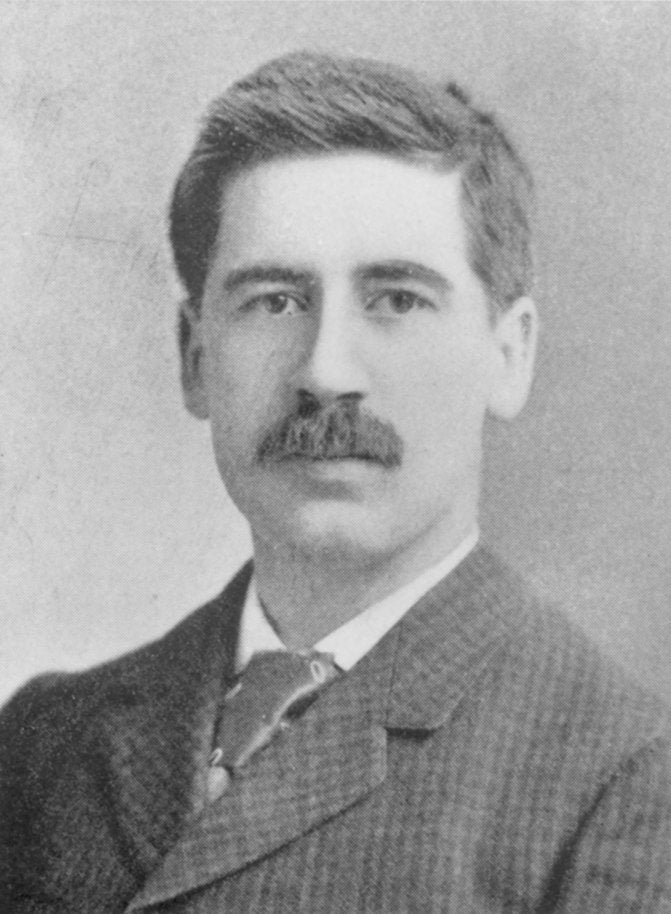

Edward Potts Cheyney, a historian of European history, was born on January 17, 1861 in Wallingford, Pennsylvania, the fourth son of Waldron J. Cheyney, a chemical and mining industries businessman, and Fannie Potts. He was first educated at country schools, then at the Penn Charter School in Philadelphia, and eventually at the University of Pennsylvania.

While an undergraduate, Cheyney was a member of the Philomathean Society and of his class executive committee. He graduated with a B.A. from the University in 1883. After a brief sojourn in Europe, he returned to enter the University’s newly-founded Wharton School of Finance, from which he received a bachelor’s degree in finance in 1884.

Cheyney began his study of history under John Bach McMaster, a member of the Wharton School faculty, but never received a doctorate. At the time, there were few professional historians in the United States and few prospects for doctoral students in history, a factor that might help explain why Cheyney never pursued a Ph.D.

Cheyney began his fifty year teaching career at the University of Pennsylvania as an instructor in history, Latin, and mathematics. He became assistant professor of history in 1890 and professor in 1897. While teaching at the University, he married Gertrude Levis Squires in 1886; they later had three children.

Cheyney’s first historical publications explored topics in American history, but he soon turned to English history with his first significant work, Social Changes in England in the Sixteenth Century, published in 1895. For the next five years, he co-edited a series of source materials in European history for use in graduate seminars with his colleagues James Harvey Robinson and Dana C. Munro. His concern for improved teaching extended throughout his career into publications and textbooks, including An Introduction to the Industrial and Social History of England (1901), A Short History of England (1904), and Readings in English History (1908). He joined the American Historical Association in 1890, becoming an influential member in 1901 with his election to the AHA’s executive council.

Cheyney’s writings reveal his preferences for “scientific history,” a prevailing historical school of thought at the turn of the century. His earliest work adhered strictly to that conception of the historical enterprise; thus, he viewed the task of the historian as dispassionate and objective. Cheyney’s 1923 presidential address to the AHA, titled “Law in History,” vehemently defended his idea of scientific history and defined six “immutable self-existent” laws of continuity, interdependence, impermanence and mutability, democracy, necessity for free consent, and moral progress that determined the progress of human history.

To that conception of scientific history, Cheyney added his commitment to “New History,” an interpretive school sympathetic to school science that encouraged scholarly exploration outside of the conventional fields of politics and institutions into all dimensions of human activity. For Cheyney, the most significant historical development was the simultaneous growth of nationalism and individual freedom. In An Introduction to the Industrial and Social History of England, he defined “socialism,” which occupied a prominent place in British political thought, as merely the willingness to consider the general good over individual preference.

Cheyney’s later work came to focus most intently on the development of England as a nation. The same year that he published A Short History of England, which has since been regarded as a standard text in the field, Cheyney produced European Background of American History, 1300-1600, a book that argued that American history was mostly an extension of European, and more specifically, of English history. His most ambitious and substantial contribution to the field of scholarship was A History of England: From the Defeat of the Armada to the Death of Elizabeth with an Account of English Institutions during the Later Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Century (2 vols., 1914-1926). While his study added much detail to the discussion of a period previously neglected by historians, it was largely conventional and seen by critics as lacking new insights into historical interpretation of the period. His scholarship did, however, advance his career professionally, and in 1929 he was appointed Henry Charles Lea Professor of History.

In 1934, Cheyney retired from teaching and assumed a position as curator of the Henry Charles Lea Library at the University. Two years after his retirement he also broadened the scope of his scholarship, publishing The Dawn of a New Era 1250-1453 (1936), a book that looked at the economic and religious history of early modern Europe. His new interpretative work reflected elements of an earlier study of social reform, which formed the basis for his 1928 Lowell Institute lectures. Those lectures were subsequently published as Modern English Reform, From Individualism to Socialism (1931).

Following his retirement, one of Cheyney’s close associates at the AHA, John Franklin Jameson, published a commemorative essay in Portrait of a Historian (1935) praising Cheyney’s contributions to the historical profession as chair of the American Historical Review and president of the AHA. Two institutions also honored Cheyney by choosing him to spearhead their projects. In 1938, the Social Science Research Council, of which Cheyney was an active member, asked him to direct a study of freedom of inquiry in the United States. His findings were later published as a series of essays in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in December 1938. The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania also invited Cheyney to write a history of the University in celebration of its bicentennial. Cheyney completed the project in 1940 and published his History of the University of Pennsylvania in conjunction with the University’s bicentennial festivities.

Cheney died of a heart attack at the age of 86 in Chester, Pennsylvania.